Love and Rockets has been called “the great American comic book” on more than one occasion, and with good reason.

It is definitely one of the greatest comic books of all time, American or otherwise, if for no other reason than it was one of the first to demonstrate the potential that comics have, beyond action adventure or childish comedy. More importantly, it has lived up to that potential for over forty years.

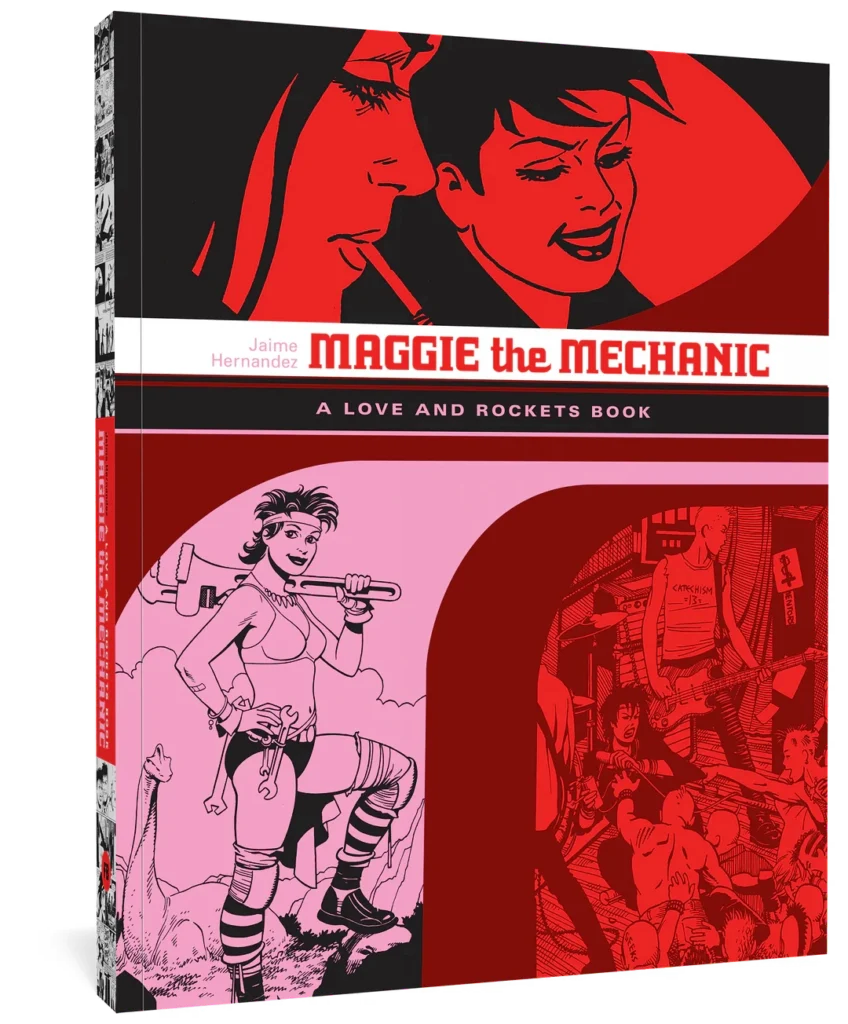

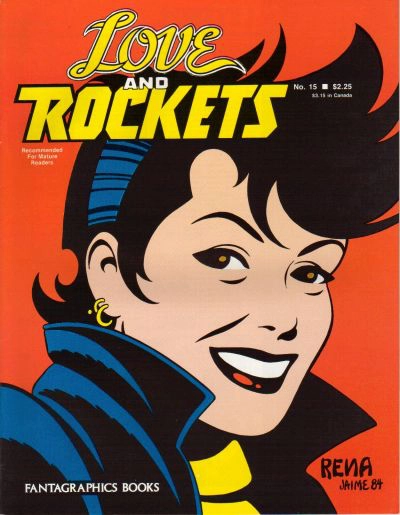

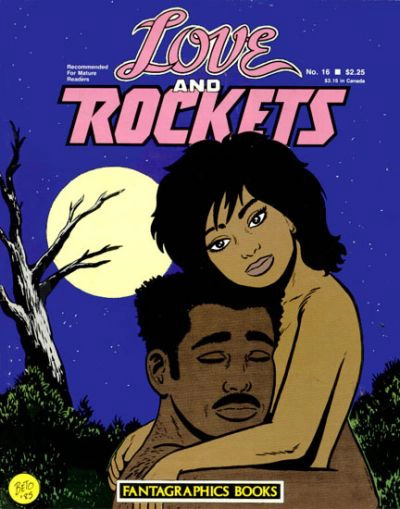

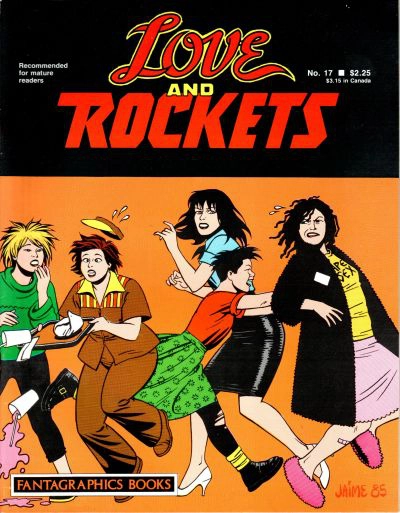

Love and Rockets volume 1 issues 15, 16 and 17 covers. © Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez.

For the uninitiated, Love and Rockets is a long-running (43 years and counting) series written and drawn by two brothers, Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez. Each Hernandez brother has his own separate narrative: Jaime’s Locas stories about a group of friends in the southern California punk scene, and Gilbert’s Palomar tales, focused on the colorful, eccentric residents of a small village in Central America.

Reading Love and Rockets is less like starting an epic novel and more like checking in with old friends. Jumping into the series for the first time is like joining a new community – you might get a brief introduction to the various characters, but it’s on the reader to figure out who is who and what is going on. By 1986, the series had been coming out for four years, and both Hernandez brothers were at the absolute top of their game.

No Cars, No Phones, No Television

Gilbert’s Palomar stories aren’t a sweeping saga so much as a series of anecdotes about the people who live in a small Central American village. In 1985’s “An American in Palomar,” Gilbert makes the succinct point that Palomar’s lack of modern conveniences such as phones and television is a strength rather than a weakness. The story concerns an American photojournalist who arrives in Palomar to tell the story of a poverty-stricken, dying town. Instead he finds a vibrant, thriving community, but he’s so hung up on American standards of living that he just can’t see it.

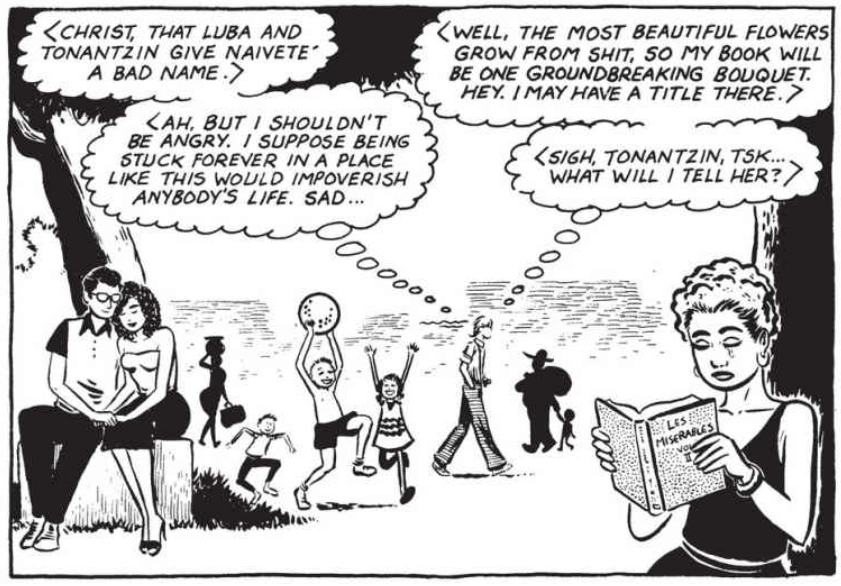

“Love Bites” in issue 16 (March 1986) gives us a variation on that same theme with a story about Heraclio, Palomar’s resident intellectual who works as a teacher in a neighboring town. He struggles to explain the value of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to his wife Carmen, who doesn’t appreciate his literary enthusiasm. After a conversation about classic literature with one of his colleagues as she gives him a ride home, we are left wondering just what benefit he gets out of living in Palomar. The point is driven home when he defends Luba, the operator of Palomar’s bath house and frequent target of gossip, from Carmen’s somewhat uncharitable comments. This of course leads to a fight that sends Heraclio straight to the bar and later, in a drunken stupor, to Luba herself.

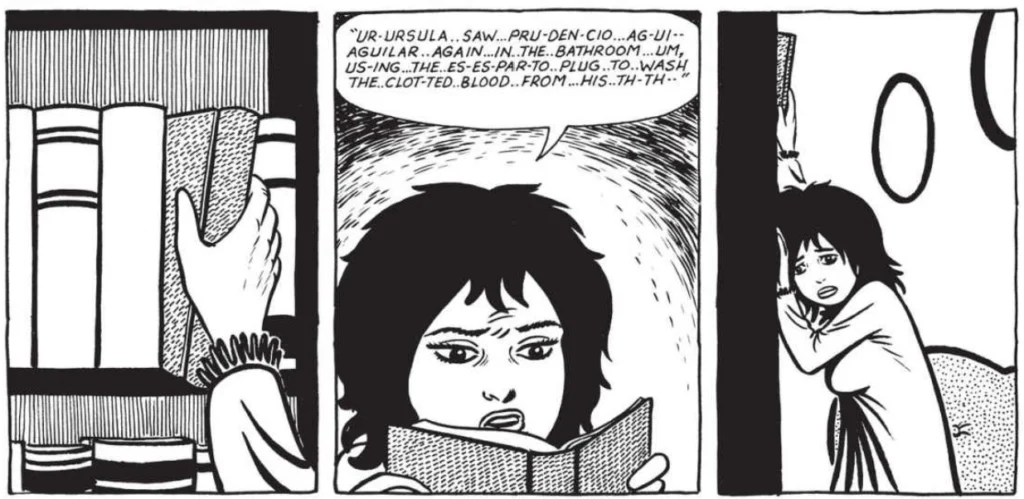

It turns out that Heraclio is a little bit fixated on Luba – he lost his virginity to her years earlier. Luba, on the other hand, barely remembers him, but far from being the maneater she’s often accused of being, she listens to his drunken rambling about how in love with Carmen he is. Meanwhile, Carmen tries to understand her husband better by reading a passage from Márquez’s book. Sadly, we soon discover that she can barely read, leaving this important part of Heraclio’s life closed to her.

The couple soon make up, perhaps not resolving their differences but at least trying to live with them. Gilbert will explore Heraclio and Carmen’s relationship in more detail in “For the Love of Carmen” in issue 20 the following year, one of the most beautiful, romantic stories ever committed to the comics page.

Out In the Big Bad World

The importance of community and human connection is the common thread running through all of Gilbert’s Palomar stories. “Holidays in the Sun” (Love and Rockets #15, January 1986) is a much darker tale that visits former Palomar resident Jesús Ángel, now incarcerated in what appears to be an unsupervised island prison. He fantasizes about the various women in Palomar he’s had real or imagined relationships with. He yearns for a return to intimate human contact, while drawing strength from and providing support to his community of fellow prisoners, often without realizing it.

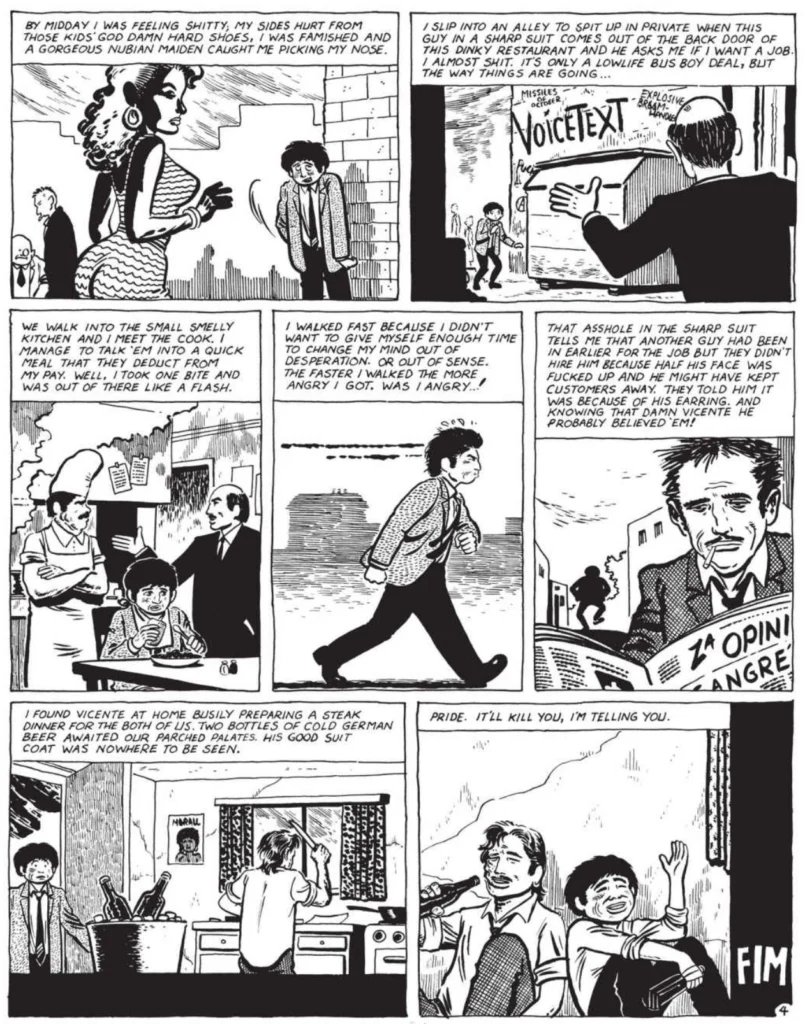

“The Way Things’re Going” (Love and Rockets #17, June 1986) illustrates what often happens when Palomar’s residents leave its storybook simplicity for the larger world. An unnamed narrator describes his relationship with his housemate Vincente (formerly of Palomar) as the two of them struggle to find work and make ends meet. Tensions are high and tempers occasionally flare, but in the end the moral seems to be that as long as they have their friendship and connection to each other, they’ll be all right.

Going Home Again

Palomar often seems to symbolize innocence, family and safety, in contrast to the world outside which usually consists of bleak, “grown up” things like prison and unemployment. As later chronicled in “For the Love of Carmen,” Heraclio chooses to move back to Palomar after college, possibly a metaphor for his decision to become a teacher and remain in the relative safety and security of academia.

Certainly, the stories that take place within the village are usually more fanciful. Even when they deal with adult themes like sex or domestic violence, there is an unreality to it that often makes it seem like a childhood memory. However, that is not to say that these are children’s stories, they are often quite the opposite, and Gilbert Hernandez will often play with that expectation to create moments of drama, sometimes even bordering on horror.

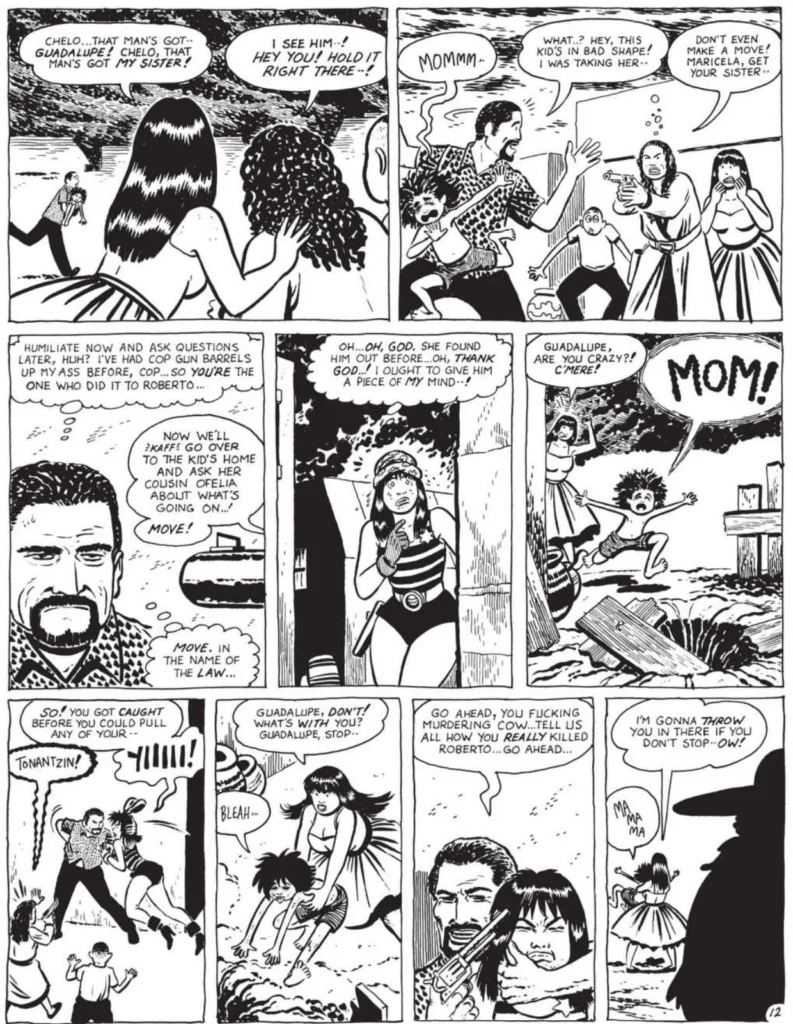

“Duck Feet,” a comparative epic at 28 pages spread across issues 17 and 18, has the whole town in an uproar as an escaped fugitive, an outbreak of disease, and a visiting stranger who may or may not be a bruja, all combine to create chaos and panic. The narrative starts with Palomar’s sheriff Chelo chasing a wanted man, in a sequence that demonstrates the author’s incredible cartooning prowess. He uses just the right amount of exaggeration to convey action and movement, while keeping the figures realistic enough to be taken seriously when the story calls for it.

Meanwhile, Somewhere in Southern California

Jaime Hernandez may well be one of the greatest cartoonists ever to put pen to paper. His command of anatomy and perspective are flawless, and his draftsmanship is exquisite, with every line perfect and not one out of place. By 1986 he had distilled his drawing style down to a minimalist essence that gives the reader exactly what they need to be immersed in the story he’s telling, and not a bit more. His characters are right on that edge between realism and cartoon where it’s easy for the reader to take the work seriously when the story demands it, but the occasional exaggeration for comic effect doesn’t seem out of place.

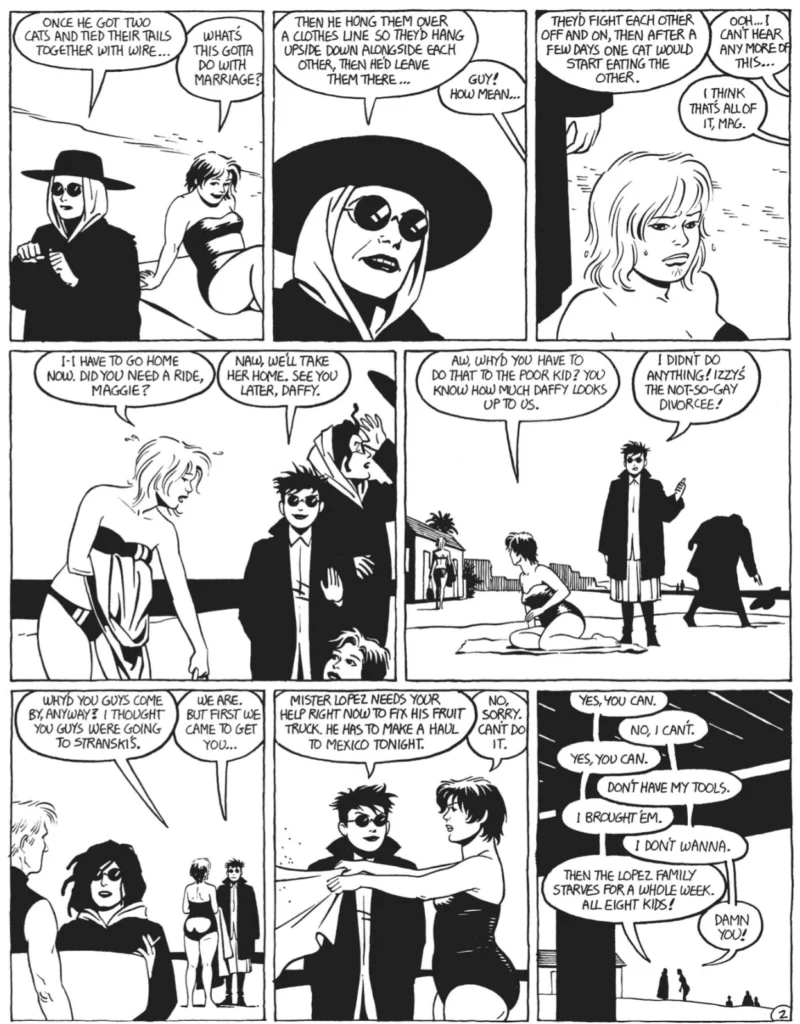

“Locas at the Beach” in Love and Rockets issue 15 (January 1986) is as good an introduction to the cast of Jaime’s Locas stories, which focus on a group of primarily teenaged, female inhabitants of Huerta, also known as Hoppers, a fictional southern California town. The story, which like most of Jaime’s tales is really more of a series of incidents, begins on the beach with lead character Maggie rolling her eyes at her friend Daffy’s very earnest plan to marry a wealthy yacht owner.

They are soon joined by Hopey, Maggie’s sort-of girlfriend – their complicated relationship forms the backbone of many of the Locas stories – and Izzy, who scares Daffy off with a story about two cats tied together as a metaphor for marriage.

Maggie is called upon to fix their neighbor’s truck, which touches upon a recurring theme throughout the Locas stories, that of Maggie’s crushing fear of success. From the beginning, Maggie is singled out as an incredibly talented mechanic, but she self-sabotages that career path at every turn over a complex combination of low self esteem and an understandable exhaustion with having to walk on eggshells for fear of crushing fragile egos in a strongly male-dominated trade.

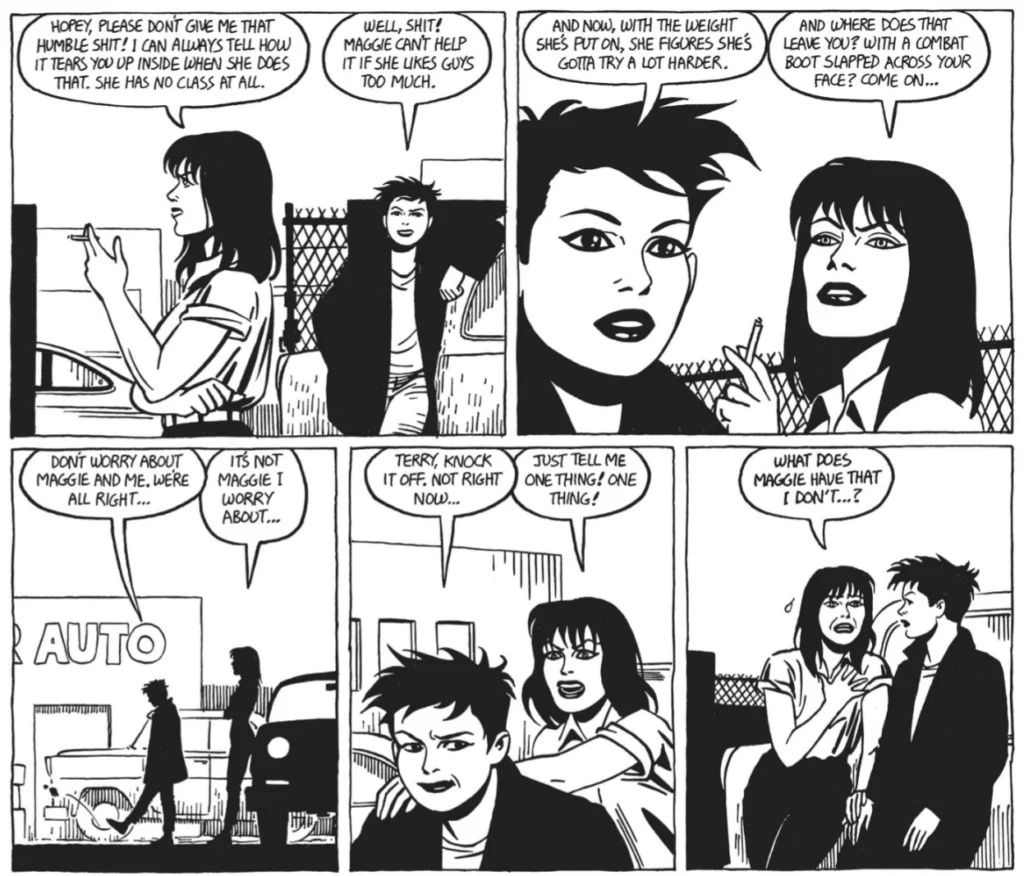

This single, densely packed eight-page story then goes on to give a moment of humanity to one of the few Locas characters who could be seen as a traditional villain: Terry Downe, Hopey’s band-mate (their punk band changes its name on a regular basis) and former girlfriend. Terry, normally a “tough girl” who talks trash about Maggie on a near-constant basis, reveals some real emotion as she tearfully asks Hopey “what does Maggie have that I don’t…?”

Back in the Days of High Adventure

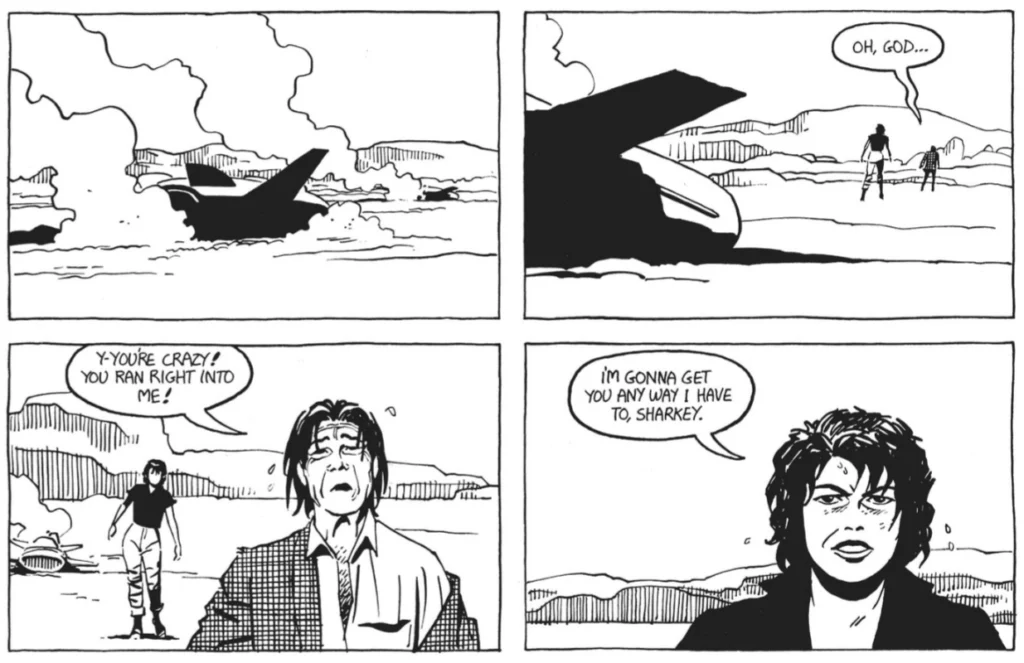

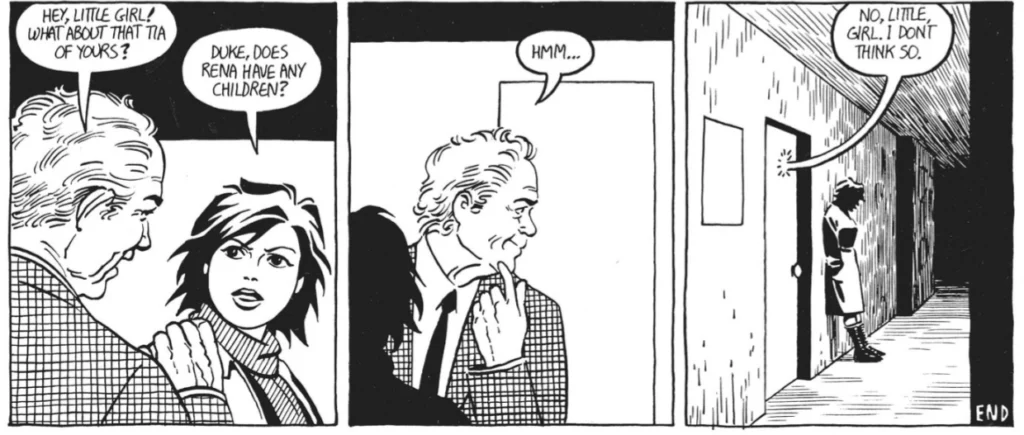

The same issue revisits a dwindling narrative thread featuring Rena Titañon, a professional woman wrestler who engages in globetrotting adventures. Stories about Rena have a “Saturday matinee” feel to them, often picking up in the middle of a storyline without any sort of exposition – they’re clearly meant to evoke a mood rather than detail a plot.

Rena’s story continues into the modern day with “House of Raging Women.” Now well into middle age and with her adventuring days behind her, Rena’s attempts to restart her wrestling career dredge up some unpleasant memories. The story leans heavily into Jaime’s oft-expressed passion for professional wrestling. Additionally, the whole thing has a melodramatic, soap opera quality to it, but Jaime’s masterful command of pacing and character keep the story moving as well as keeping the reader invested in what’s going on.

Real Life Doesn’t Follow the Three Act Structure

Most of the ‘80s Locas tales continue along the lines of “Locas at the Beach,” with each story reading like a day in the life rather than a plot-driven narrative. Very few of the stories even have titles other than some variation on “Locas,” reinforcing the idea that these are an ongoing narrative that mirrors real life, rather than contrived, structured pieces.

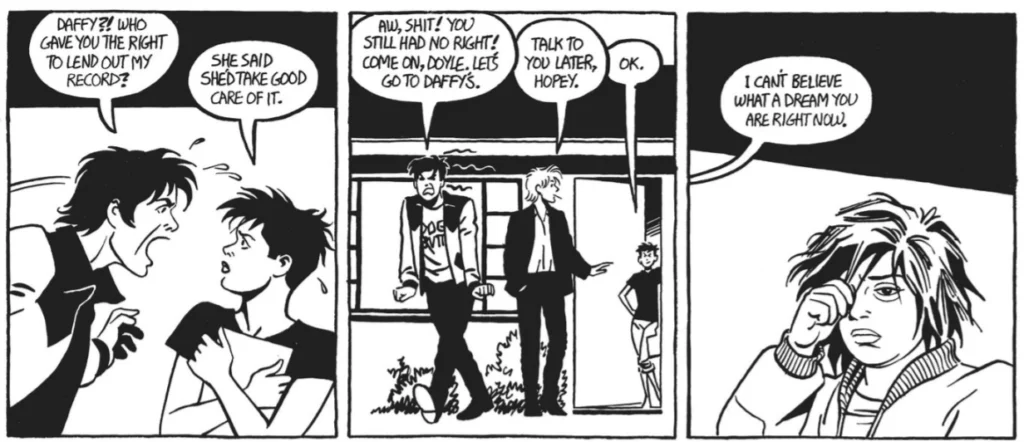

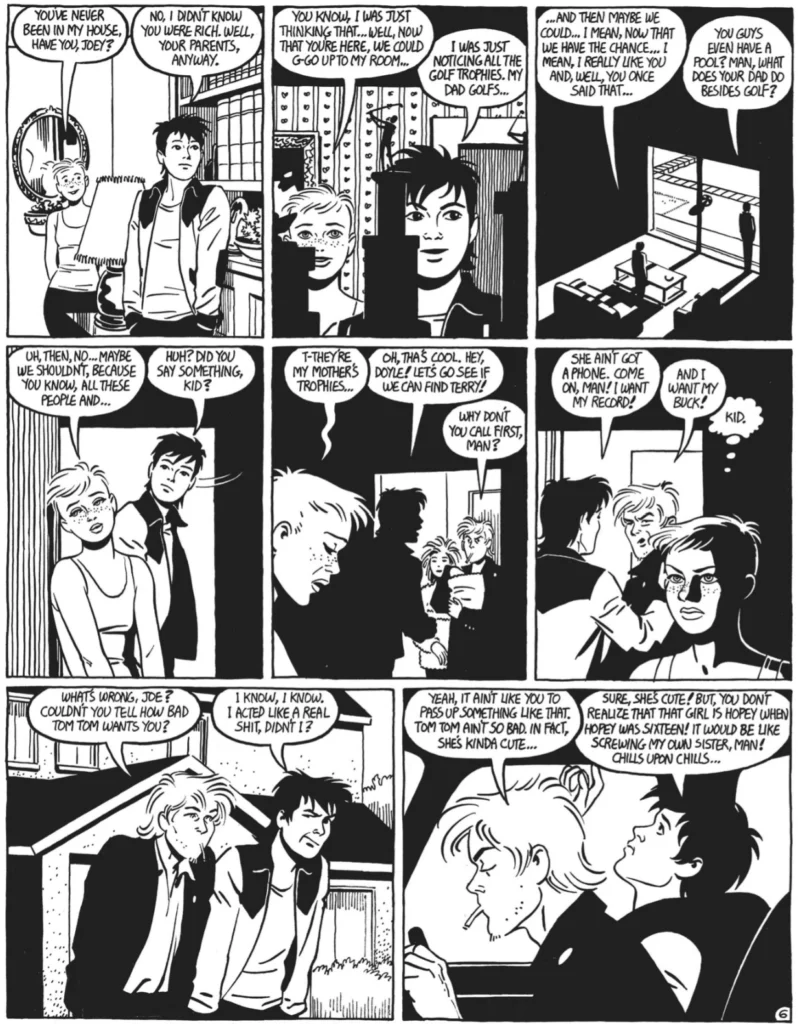

New characters are introduced as though they have always been there. “Locas vs. Locos” from Love and Rockets issue 17 gives us a whirlwind tour through the day to day lives of some minor characters, as Hopey’s brother Joey and his friend Doyle go on a wild goose chase in search of a record he lent out. His journey gives us a sense of the wider world that main characters Maggie and Hopey live in, while also demonstrating Jaime’s incredible cartooning skills.

Jaime Hernandez grew up in the southern California punk rock scene of the early 1980s, and it seems clear that he is drawing on his personal experiences both there and also as a member of the Mexican American community. But rather than fall back on potentially tedious, self-indulgent autobiography, he has created an amazing cast of fictional characters that he uses to build a view of what those communities were like. It paints a vivid picture of a time and place that is familiar and relatable without being too tied to a specific place or time.

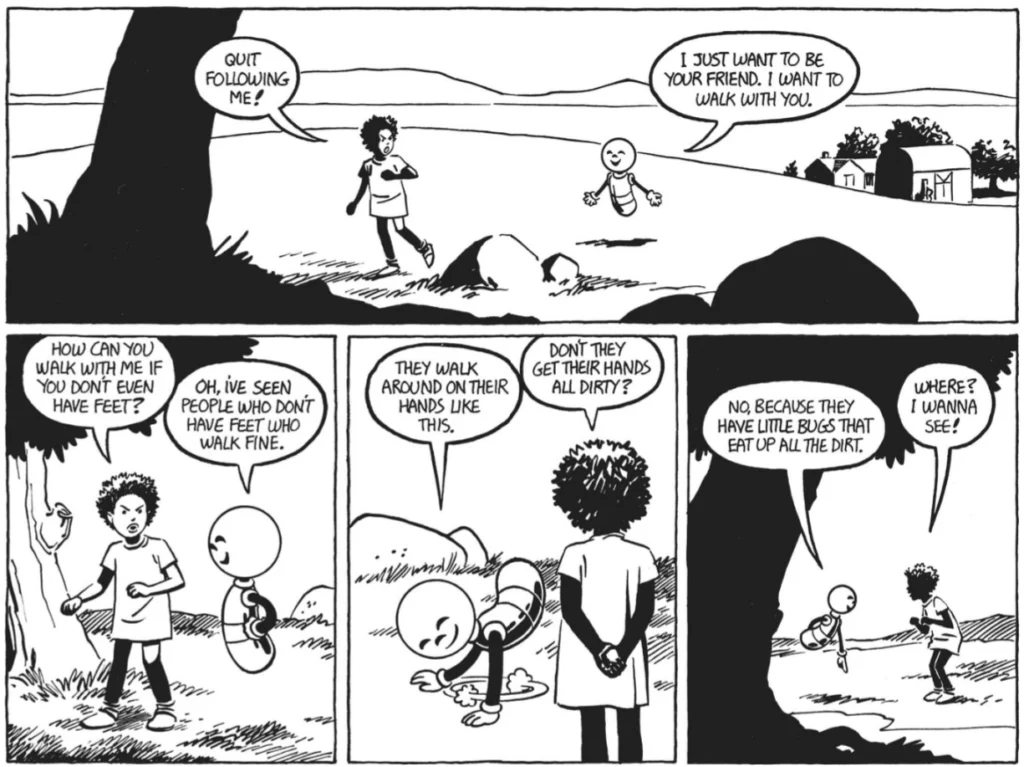

Jaime occasionally takes time out from world-building to indulge in more whimsical flights of fancy. Appearing in the same issue, “Rocket Rhodes” reintroduces us to Rocky Rhodes and her robot pal Fumble, intergalactic explorers who first appeared in Love and Rockets issue 2. The scant four pages once again demonstrate his incredible talent for economy of story, as he gives us exactly what we need to understand what the piece is about, and not a bit more.

Unlike Any Other

Love and Rockets was a success from the moment it first appeared because there was nothing else even remotely like it. To this day, there still isn’t. Both Jaime and Gilbert have allowed their characters to age in real time, with Gilbert following the children of his original Palomar characters as they navigate their somewhat cynical lives in the United States, and Jaime following Maggie and Hopey as they contend with middle age.

I don’t think there are any other comics creators who have done the same characters consistently for forty years. There certainly aren’t any doing it with the incredible level of skill and insight that the Hernandez brothers are bringing to Love and Rockets.

Where can you read it?

Single issues of Love and Rockets volume 1 can be a little hard to find, but publisher Fantagraphics has been good about keeping all of the Hernandez brothers’ work in print. Currently the best place to start is with The Love and Rockets Library, a 15 volume collection of most (if not all) of the material from the first 50 issues and the various one-shots and miniseries that followed. The stories I have discussed above appear in Heartbreak Soup, Maggie the Mechanic, and The Girl From H.O.P.P.E.R.S. – those three volumes are an excellent place to start.