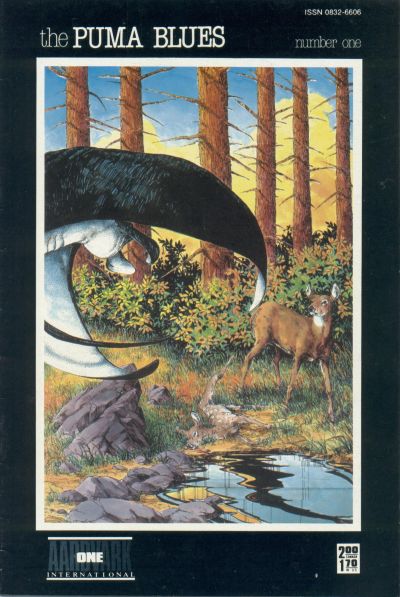

Only in the 1980s could a comic book like The Puma Blues see publication at all, let alone run for 23 (and a half) issues.

The bleak, contemplative black and white series came along at just the right time: smack in the middle of the comics industry’s most fertile period of creative growth, before the excesses of the 1990s or the Hollywood gloss of the 21st century. There was a growing audience for sophisticated work that might depart from the plot driven action adventure that still dominated the field (and seemingly always will).

The book’s road to publication started with an astonishingly lucky break. According to the introduction in Dover’s 2015 hardcover reprint of the series, creators Stephen Murphy and Michael Zulli approached Cerebus auteur and self-publishing guru Dave Sim at his first-ever mall comic book shop signing. In spite of having just decided to stick to only publishing his own series, Sim was so taken by the work that he immediately offered to publish it. And did so, for its first 17 issues, until a dispute between Sim and Diamond Comic Distributors forced Murphy and Zulli to self-publish the next three issues. The book then moved to Mirage Studios (home of the massively successful Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles) for what would be the last three issues of the series, followed by a self-published issue “24½” mini-comic. The story wasn’t completed until Dover’s 2015 omnibus reprint, in which the publisher offered Murphy and Zulli the chance to complete their epic.

The future, as seen from the past

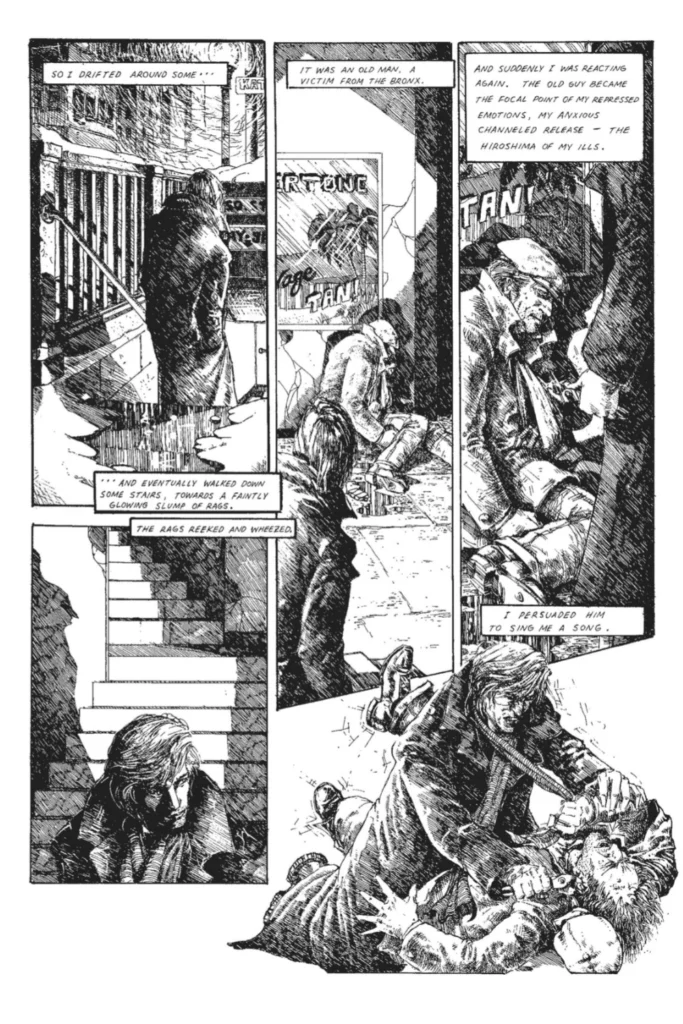

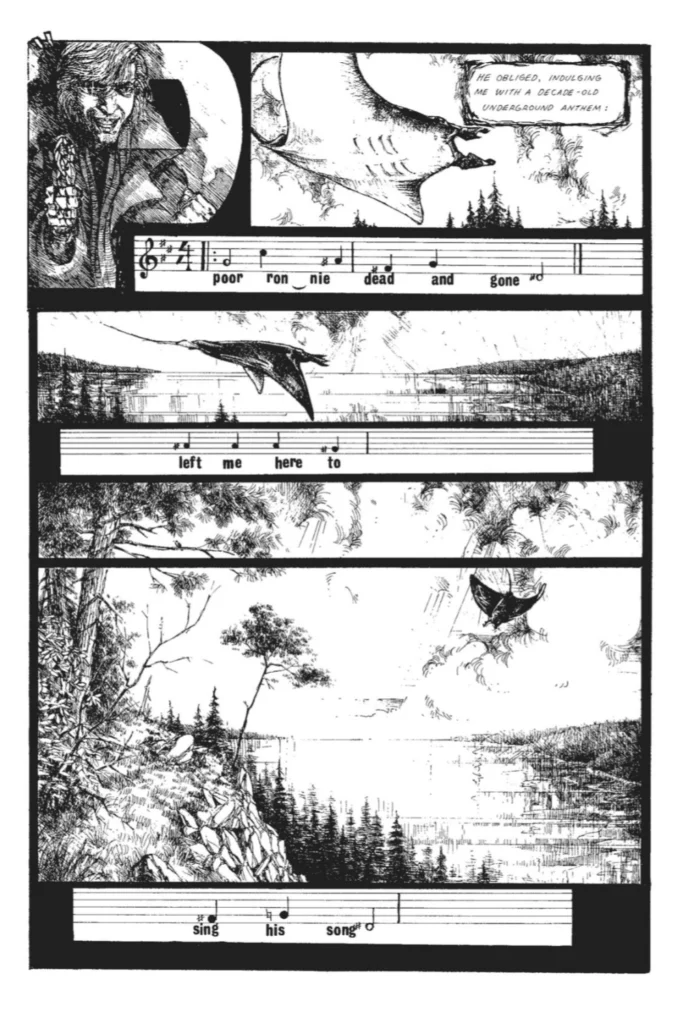

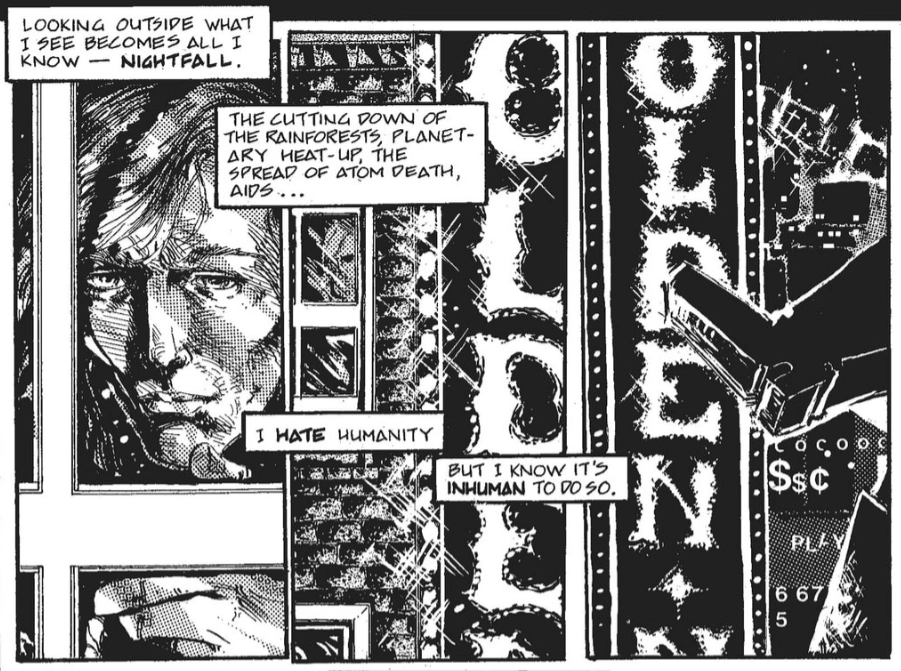

The first issue starts by setting up what appears to be an urban horror story of the type that would become ubiquitous in the early 1990s. We are introduced to 21 year old Gavia Immer – trenchcoat wearing, spiky haired and angst ridden, giving us an internal monologue as he wanders a dystopian cityscape in the year 1997 (11 years into the future from the comic’s publication date). As he muses over the death of his father one year previously, he appears to assault a street person with a pair of pliers. But after three pages, the setting and tone abruptly shift to a woodland setting populated by a manta ray inexplicably flying through the air. We appear to be in a different sort of story all together.

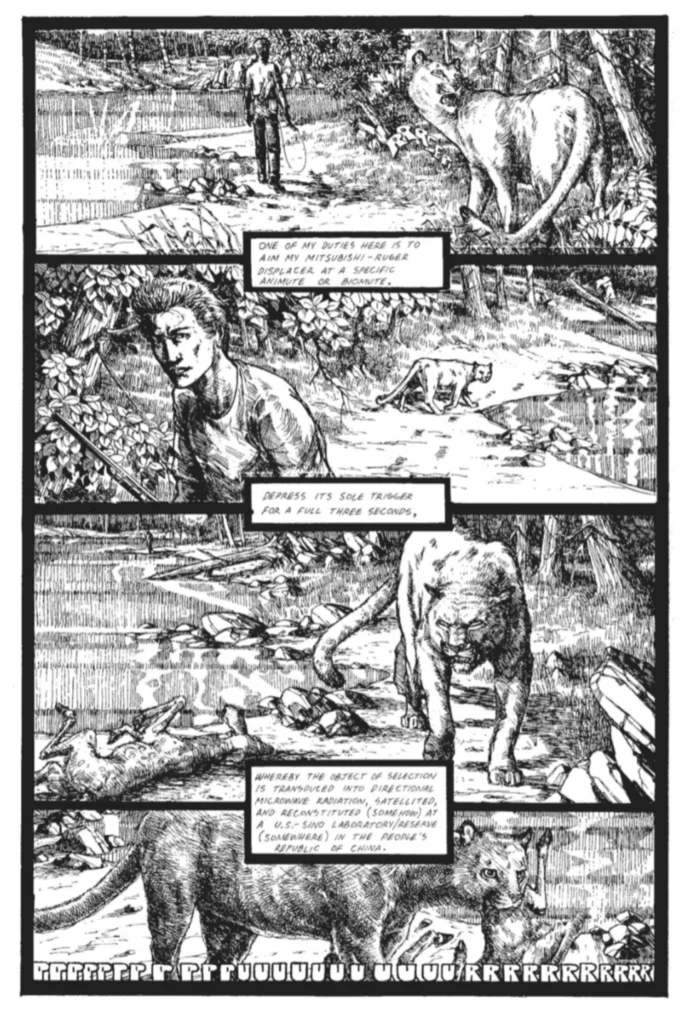

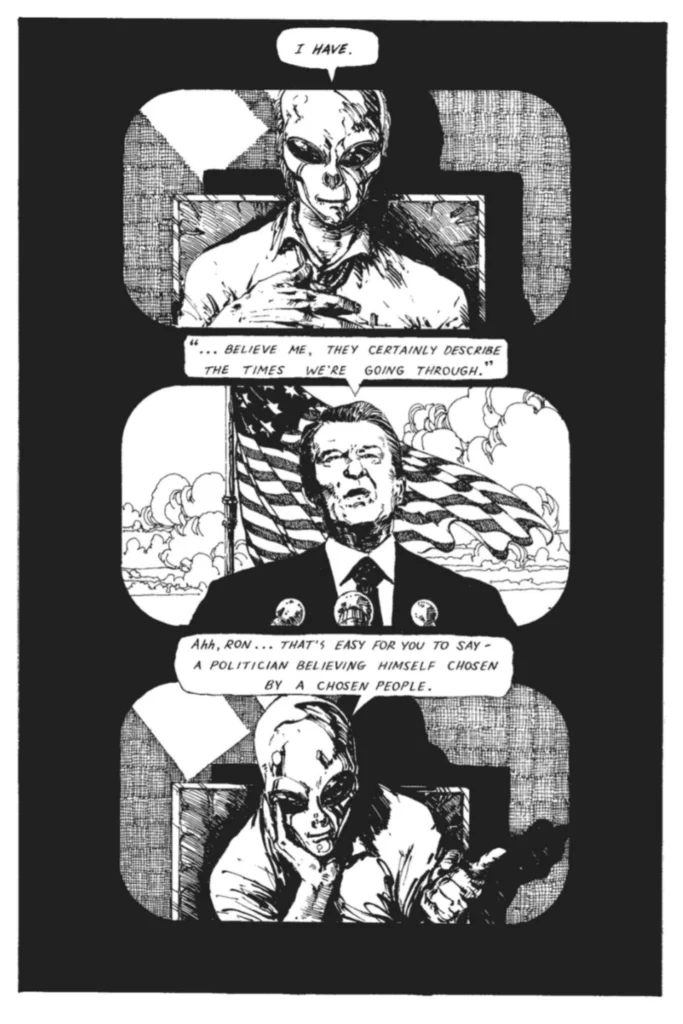

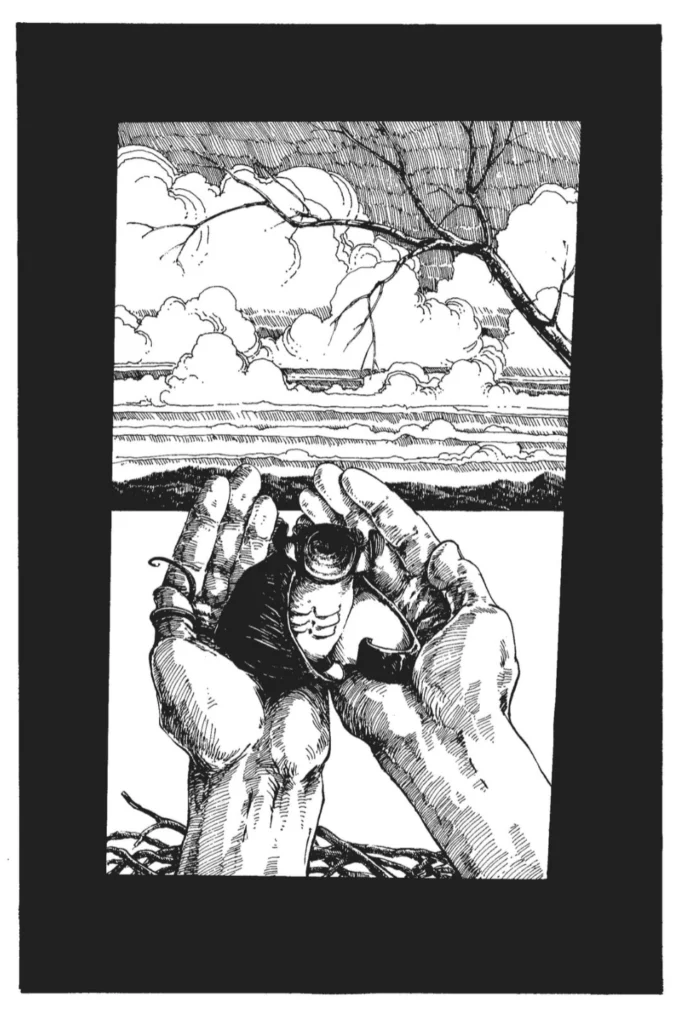

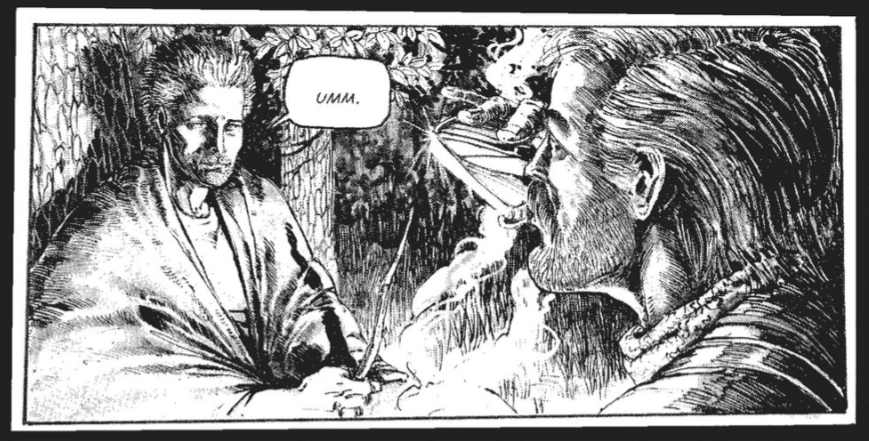

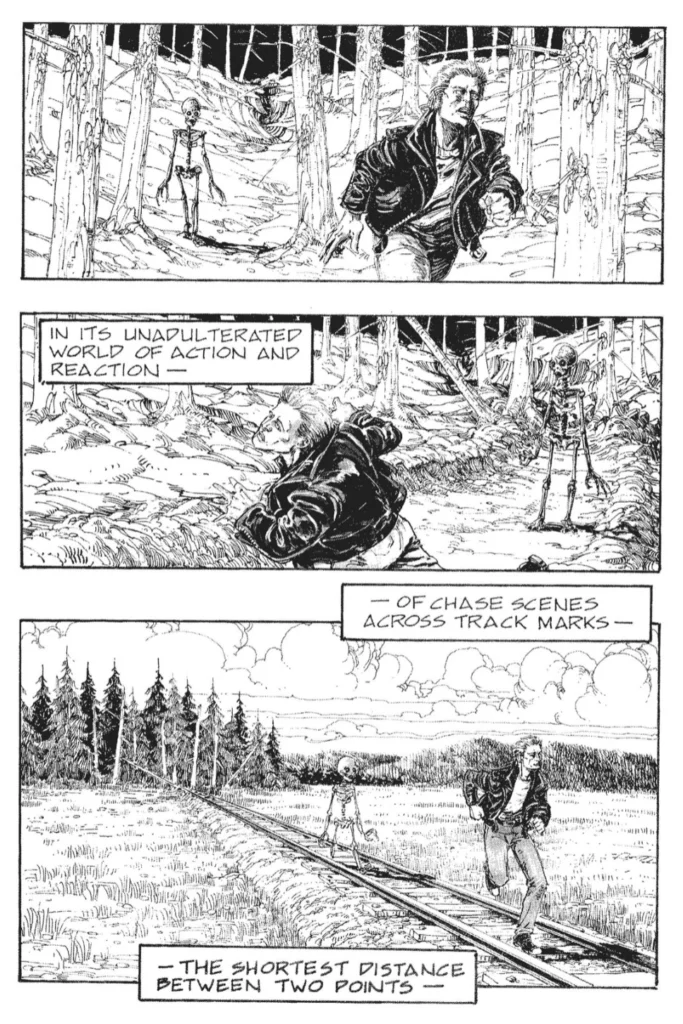

Pages from The Puma Blues #1. © 2015 Stephen Murphy and Michael Zulli.

It is three years later, and Gavia is now serving in an unspecified military organization, assigned to a solitary post monitoring a reservoir and its surrounding wilderness. Part of his job is to track the flying manta rays and other mutated animals, and use a “displacer rifle” to teleport them to a laboratory in China for further study. As he wanders the wilderness in search of his “prey,” he is in turn stalked by a solitary puma, at least until an easier meal comes along. The puma will appear here and there throughout the series, although its symbolism and purpose is unclear.

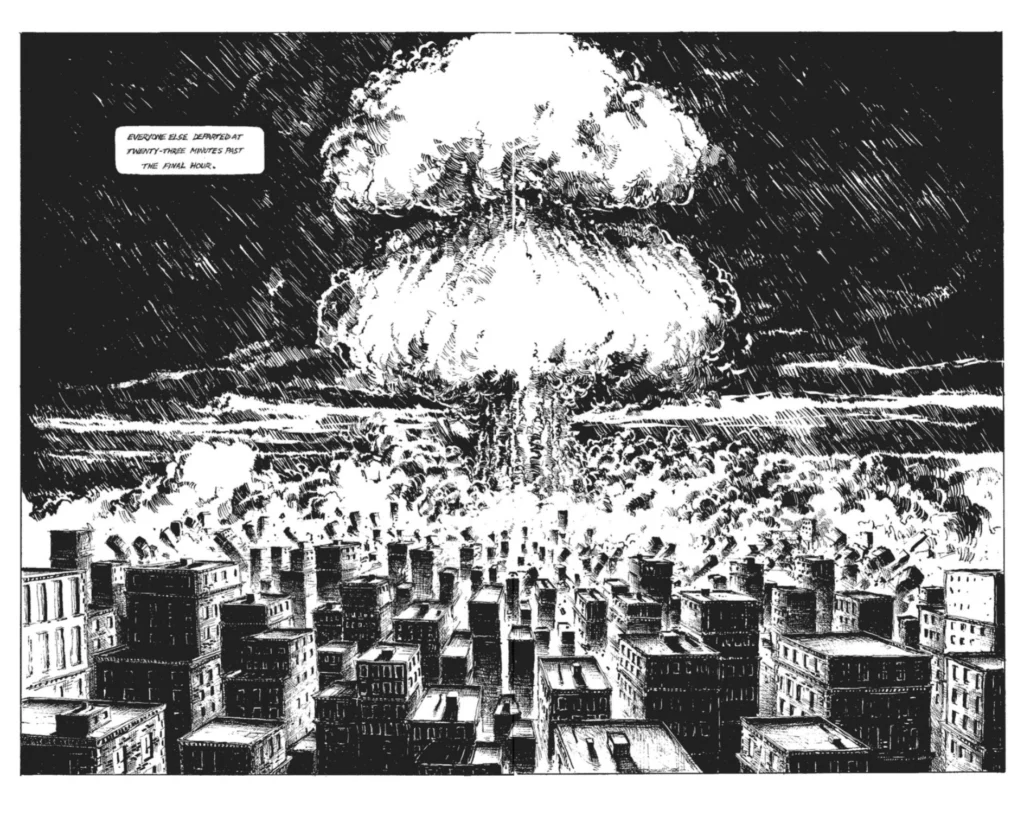

The first issue ends with some much needed exposition in the form of a teletext (a TV-based news feed that was gaining popularity in the 1980s). Through a series of headlines and short news pieces we learn a bit more about the near-future setting. It is a future of eccentric android servants, Soviet moon bases and commercial passenger space shuttles, but also of war in the Persian gulf, proposed forced sterilization of third world countries as a form of population control, and barely effective efforts to mitigate runaway pollution. More directly relevant to the story are hints that domestic terrorists detonated a nuclear weapon in the Bronx five years previously.

In spite of the near future setting and science fiction trappings such as androids and teleportation, this is not a plot-driven adventure story. Writer Stephen Murphy makes great use of symbolism and allegory to ruminate on the near-crippling existential angst felt by so many who were coming to terms with social and environmental issues of the 1980s.

The apocalypse will be televised

Gavia’s assignment comes with a fair amount of down time, which he spends watching a series of films made by his father. The films are best described as “subjective documentaries,” hovering in a grey area between reportage and expressionism. While the first of these films is used to provide some detailed back story about the nuclear explosion in the Bronx, these sequences are really about giving voice to the author’s thoughts on society’s collective existential crisis. The films Gavia watches can delve into surrealism, symbolism and exposition in a way that doesn’t bog down the overall narrative, at least for now…

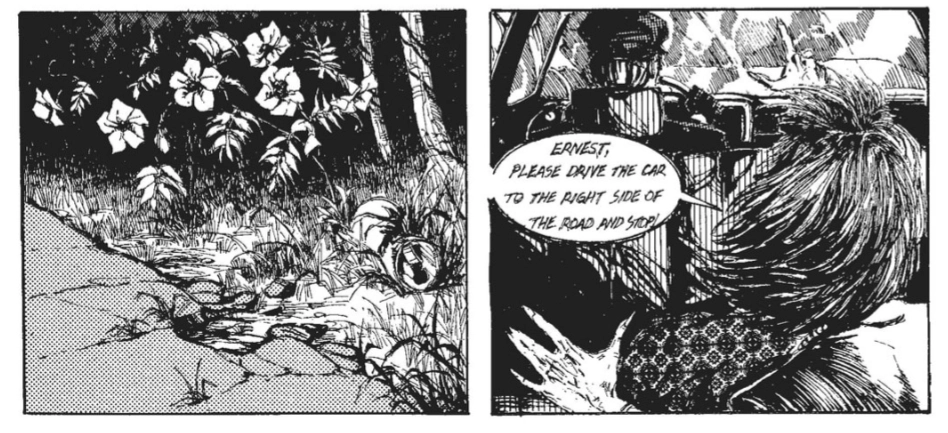

One of the series’ more subtle but powerful sequences is a brief interlude involving is Mrs. Malcolmson, a wealthy invalid surrounded by android servants, including a particularly eccentric chauffeur called Ernest. Mrs. Malcolmson instructs Ernest to pull over while on a drive near the reservoir. She has spotted a cast off soda can next to some flowers on the side of the road. But in a scathing symbolic commentary about society’s response to environmental pollution, she instructs her servant to pick the flowers for her, leaving the trash where it is.

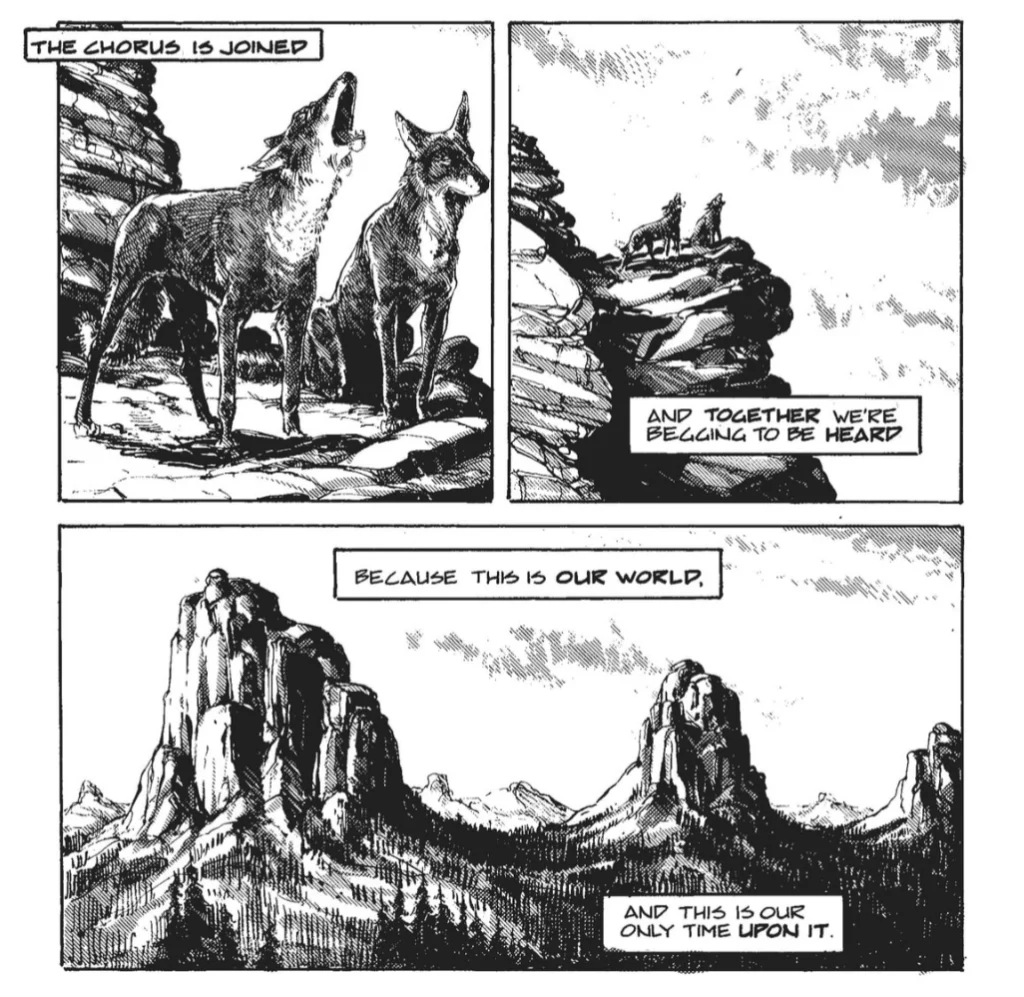

Scenes from nature

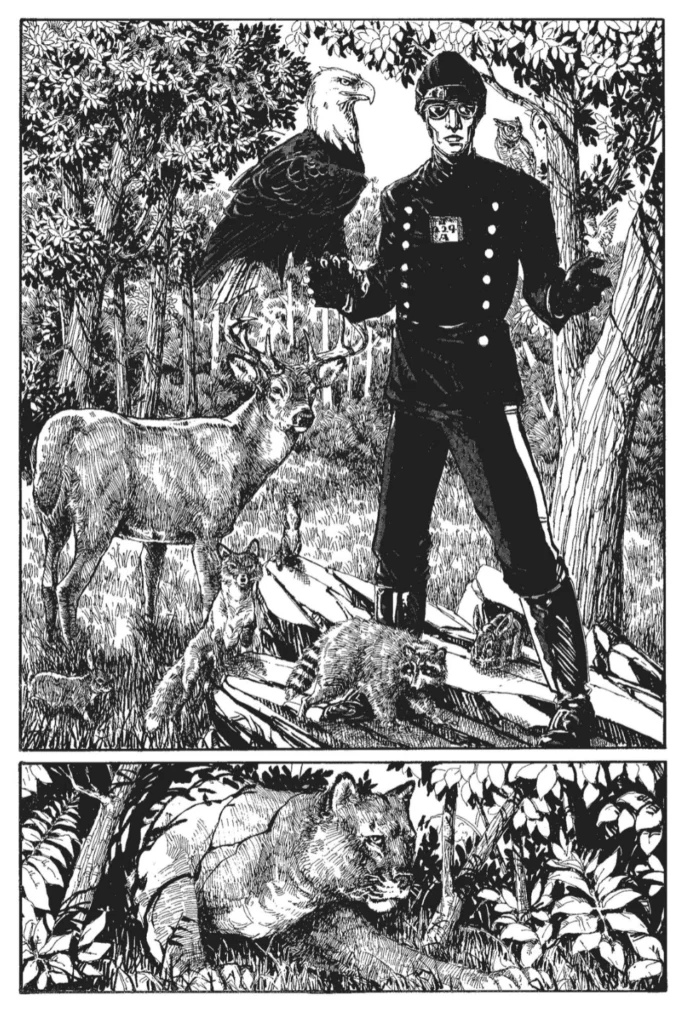

After picking flowers for his mistress, Ernest the chauffeur android asks permission to wander off into the restricted wilderness surrounding the reservoir, where he is able to commune with the resident animals – only the puma seems to view him with suspicion.

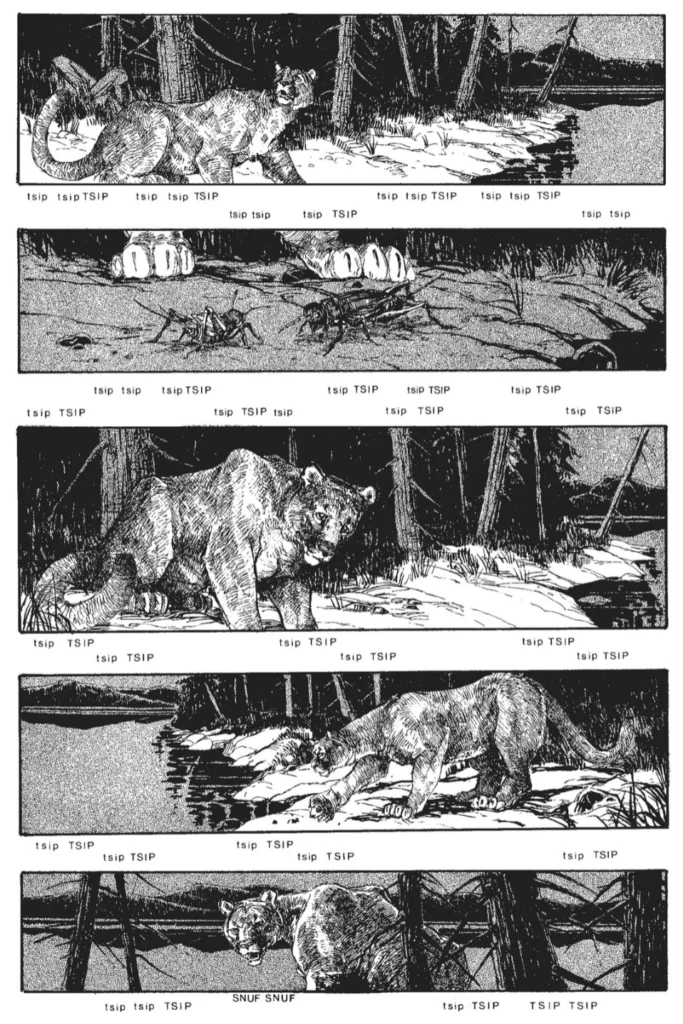

The story of Gavia and the other characters is frequently intercut with wildlife scenes, and this is one area where The Puma Blues, and artist Michael Zulli, really excel. Issue 5, “In the Empire of the Senses” is almost entirely without dialogue or human characters, instead depicting a night in the life of the puma as he stalks through the area surrounding the reservoir. Text sound effects at the bottom of each panel make an attempt to depict how deafening nature can be, especially at night.

What’s it all about?

Murphy and Zulli spend the first seven issues of The Puma Blues establishing the contemplative tone of the book. They introduce Gavia Immer and a small cast of supporting characters, most of whom will be dropped by the end of the second story arc. In issue 8 Gavia sits down to watch his father’s second documentary, “AlieNation,” and we finally find out what The Puma Blues is actually about.

This book is about society’s willful ignorance in the face of Armageddon.

The film (as depicted in the comic via snapshots) begins with a voice over, presumably from Gavia’s father Ganz, alongside clips of twentieth century luminaries as diverse as Jim Morrison, Sigmund Freud, and Ronald Reagan. Eventually Ganz gets to his point:

“I see it as what happens when a given society chooses the reality it wishes to live in by selectively processing only that input that conforms…to that reality…and whereby all else remains background noise… Particularly those elements that appear ominous…”

Ganz’s opening narration seems to criticize the religious right’s need to explain everything in relation to biblical scripture, but at the same time he appears frustrated by society’s seeming apathy regarding the precarious state of the world. He goes on to posit that the Bible may have predicted Chernobyl, questioning whether reality is absolute or based entirely on individual perception.

“While a rise in UFO sightings may be argued away as a manifestation of a society struggling through another spiritual re-awakening, I began to ask myself what proof had I that UFOs were either real or unreal? Physical or psychological? I had no basis for any form of certainty, and I needed to know. At that point I could only file UFOs as another insubstantial belief system. Having previously dismissed the entire phenomenon, thinking it another useless mindgame that served to focus human attention away from the Earth. And away from reality.”

The monologue goes on to ponder whether the UFO abduction phenomenon of the late 1980s might be an expression of Jung’s “collective unconscious” – a new mythology created to explain away the human race’s fundamental feelings of unease and anxiety in the face of that which cannot easily be explained. In this case, it’s humanity’s willful ignorance in the face of the potential Armageddon posed by nuclear war, AIDS, environmental collapse, etc.

It’s heady stuff, and occasionally author Murphy is guilty of what I will call “narrative impatience.” He has so much to say that the book occasionally lapses into dense chunks of text – he’s not willing to let his ideas come out naturally through the narrative. Even the very clever device of Gavia watching his father’s films only goes so far, as the text is often way more than what would be believable as voice over in a documentary.

Back to the story, or not

Gavia spends the next two issues watching the film, his reaction seeming to mainly be eye-rolling disdain. The story then makes a brief return to its ongoing narrative as Gavia finds an infant flying manta which his superiors immediately show up in person to collect. We’re reminded that Gavia’s work at the reservoir is part of a larger agenda that he knows nothing about, but (perhaps unfortunately, perhaps not) this is the last we will see of this plotline.

Over the course of the series, Gavia strikes up a friendship with Jack, a psychology lecturer who frequently visits the reservoir even though it is closed to the public. Jack is part of a conspiracy involving the flying mantas whose purpose is never made clear. He mainly serves as another mouthpiece for the author’s ideas. There is a particularly telling dialogue exchange in issue 15 in which Jack explains the “do nothing” attitude that so many took in the face of 1980s angst:

“I grew tired being a benched receiver. Having gotten so hooked following the morose state of the world unfolding in the Times, on TV. Daily, nightly. Each new documentary more dread than the last. Huddled under a blanket curled tight upon a couch. My numb stare up through the window. Slow clouds mute reflections across eyes gone stale. A coma of denial, of acceptance…that the evil found in some of us was enough to destroy the whole of us. It was paralysis more than apathy.”

Gavia doesn’t seem to know what to do with this information. It sounds a lot like the “doomscrolling” and “outrage exhaustion” phenomena that so many of us experience today. Not much has changed, it seems.

A major shift

It was at this point that Murphy and Zulli found themselves (through no fault of their own) caught in the crossfire in a very public and acrimonious dispute between Puma Blues publisher Dave Sim and Diamond Comic Distributors. Circumstances forced them to break ties with their publisher unless they wanted to lose a major avenue of distribution, so they self-published the next three issues. Possibly coincidentally, possibly not, the series undergoes a major shift in tone. Issues 18 and 19 have a very dreamlike, abstract quality, abandoning traditional panels and word balloons in favor of caption boxes over seemingly unrelated illustrations.

Issue 18 picks up the previous issue’s scattershot narration, an attempt to emulate a television with rapidly changing channels as a way to drop in disjointed sound bites, most of which have something to do with the environmental crisis. The next issue takes us directly into Gavia’s dreams, with a clear shift in artistic style. Possibly to compensate for the surreal nature of the images, artist Zulli opts for a consistent three panel grid throughout the issue. It makes for fewer illustrations per page but larger images, which is particularly nice given the amount of detail in Zulli’s work.

After an anthology issue featuring stories and illustrations by comics heavy hitters like Alan Moore, Chester Brown, Peter Laird, and Steve Bissette, The Puma Blues moved to Mirage Studios (publisher of the astronomically successful Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles) for its final three issues.

The timeline jumps two years ahead – Gavia is no longer in the military, and has moved to the American southwest where he is shacked up with a young woman, having spent “three weeks of sex so unsafe a few more of these fascist years it’ll be made illegal…” Until now the series hasn’t really delved into AIDS and the accompanying anxiety over sex and sexual freedom that the epidemic created in the 1980s.

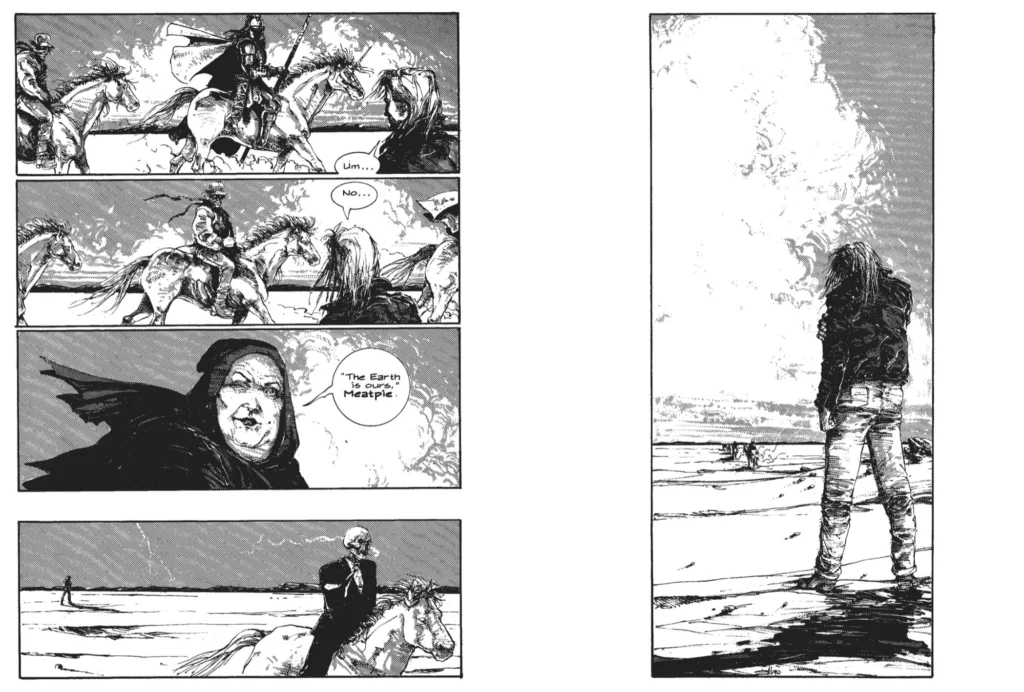

The final issues consist primarily of Gavia’s internal monologue as he visits the Trinity atomic testing site in New Mexico, followed by a tour of the Nevada atomic testing site. At this point the science fiction elements from the early issues of the series have entirely faded away, giving way to surreal, dream-like imagery that often make it difficult to determine what Gavia is really experiencing and what he is imagining. The point, tying into what his father was trying to say in his “AlieNation” film, may well be that there isn’t any real difference.

A new conclusion

The Puma Blues faded into obscurity after issue 23 and a self-published mini-comic dubbed “issue 24½.” The last pages of issue 23 present a somewhat nihilistic ending to the series, with a representation of the Biblical Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse declaring to Gavia that “…the Earth is ours.” But apparently author Stephen Murphy had more story to tell, having declared at the start of the Mirage Studios run that the series would go for 26 issues.

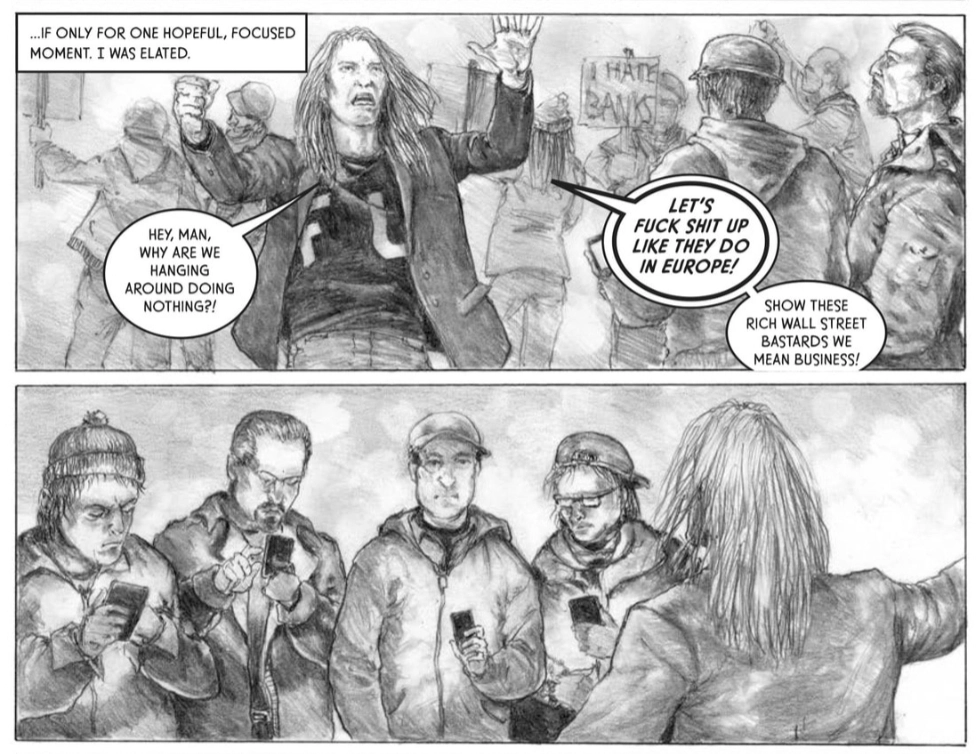

In 2015, Dover Publications reprinted the entire series in one hardcover volume, and also gave the creators a chance to do a new concluding chapter. The result is “Poor Little Greenie,” a 40-page ending that tells us what eventually happens to Gavia and near-future world he lives in. None of the other characters from the early issues of The Puma Blues are mentioned, although the flying mantas do make a brief reappearance.

The final chapter serves to bring Gavia’s story through to the 21st century, making particular mention of the Occupy Wall Street movement as yet another example of indifference and apathy standing in the way of revolution. It occasionally falls victim to Murphy’s “narrative impatience,” often relying on fairly dense chunks of text to get a lot of exposition across. It’s interesting to see how Murphy’s outlook has evolved, and even more interesting to see how it has remained the same. However, ultimately the new chapter is unnecessary and doesn’t really make the arc of the series any better.

Final thoughts

The Puma Blues stands as a masterpiece of 1980s existential angst, and while some of the details may be different now, it is frighteningly relevant today. Stephen Murphy’s writing is astonishingly thoughtful for a writer at the beginning of his career, and Michael Zulli’s breathtaking art is consistently haunting, especially the wildlife scenes which are the lifeblood of the book. It’s a seminal piece of comic book art that deserves much wider recognition.

Where can you read it?

Single issues of The Puma Blues aren’t particularly expensive or difficult to find, but the Dover reprint from 2015 really is the best value, giving you the entire run other than issue 20, plus the new material. It appears to be in print and available from the publisher, as well as the usual online book retailers. Amazon also has a electronic version available for the Kindle.