It’s no secret that Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons based the cast of characters in Watchmen on the Charlton Action Heroes, a somewhat obscure group of characters originally published by Charlton Comics in the 1960s and later acquired by DC Comics. Rather than letting Moore kill off or change the characters they had invested in, DC chose to integrate them into their superhero universe, leaving Moore and Gibbons to create similar yet different versions for their story.

Last time we looked at Blue Beetle, the Charlton character who seemed to fit in to the wider DC Universe the best, and Peacemaker, who has had a high profile recently thanks to a memorable appearance (played by former pro wrestler John Cena) in James Gunn’s Suicide Squad movie, followed by his own streaming series. We also took a brief look at Nightshade, who may or may not have been the basis for Watchmen’s Silk Spectre. Now let’s take a look at what DC did with the characters who were the inspiration for Watchmen‘s Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, and Ozymandias…

That is the Question

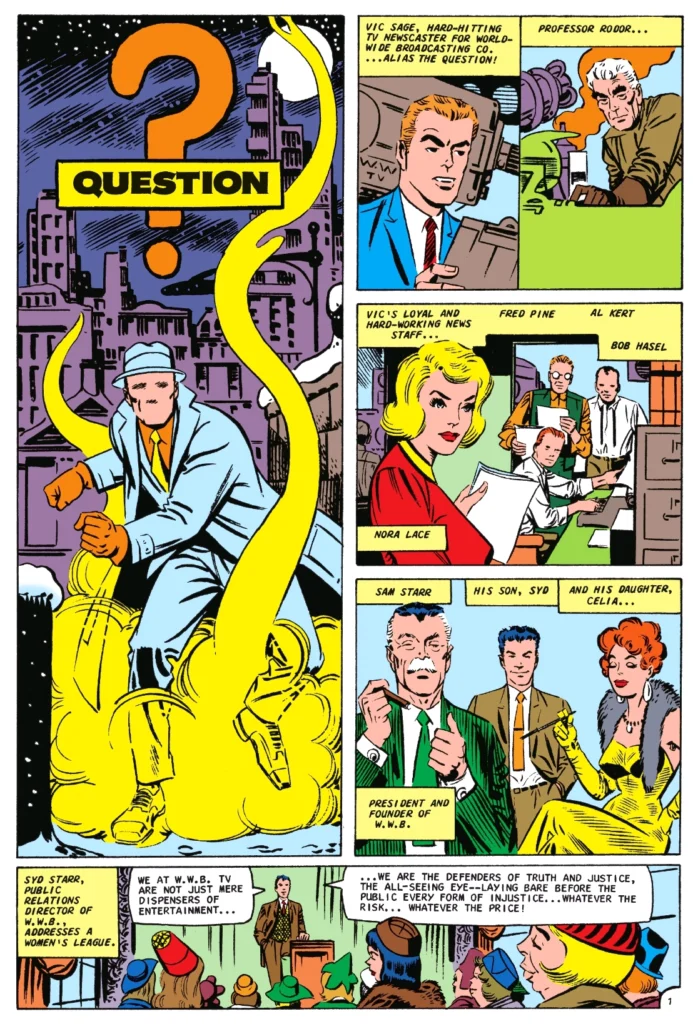

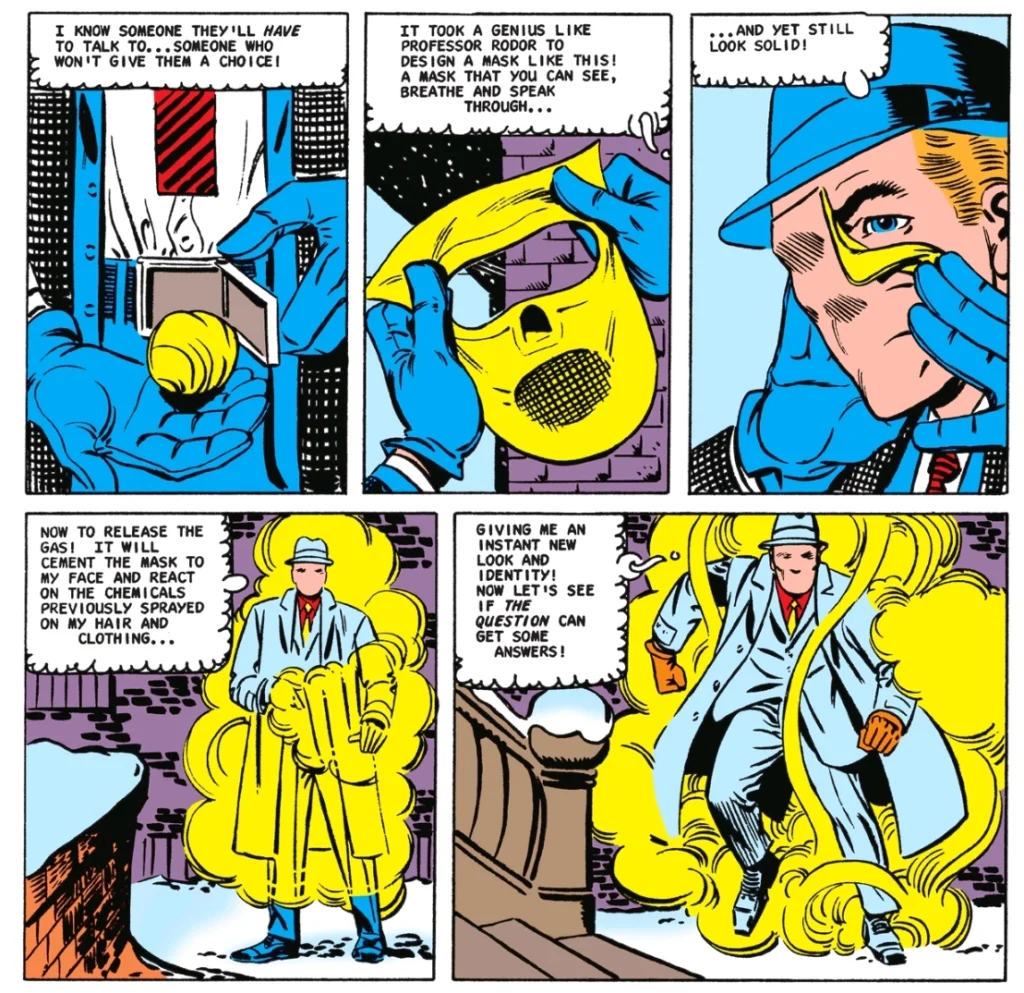

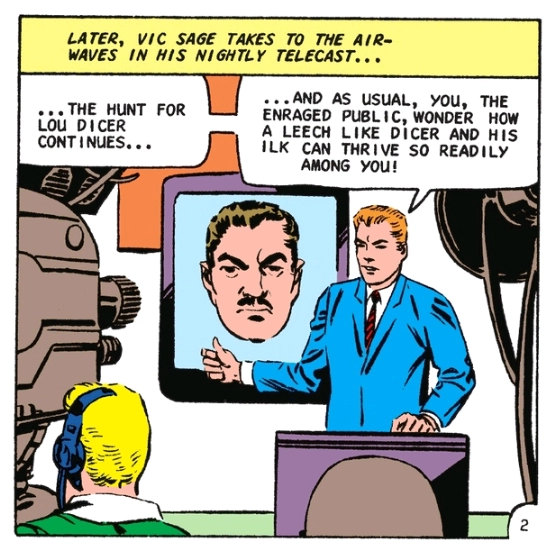

The Question first appeared as a backup feature in Charlton’s 1967 relaunch of Blue Beetle. As written and illustrated by Steve Ditko, the character is arrogant and uncompromising, and seems motivated not so much by seeking the truth as by forcing acknowledgment of his version of it. The stories lean heavily into the Question’s civilian identity of Vic Sage, crusading TV news reporter, and stands as a relatively rare example of a costumed hero whose personality does not change at all when he switches between his two roles.

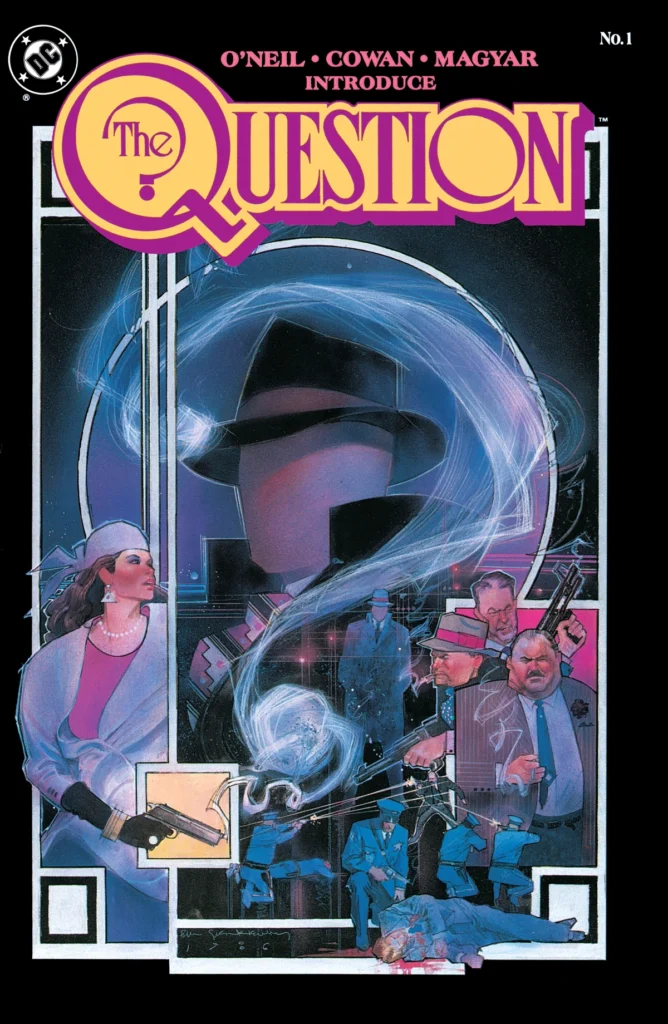

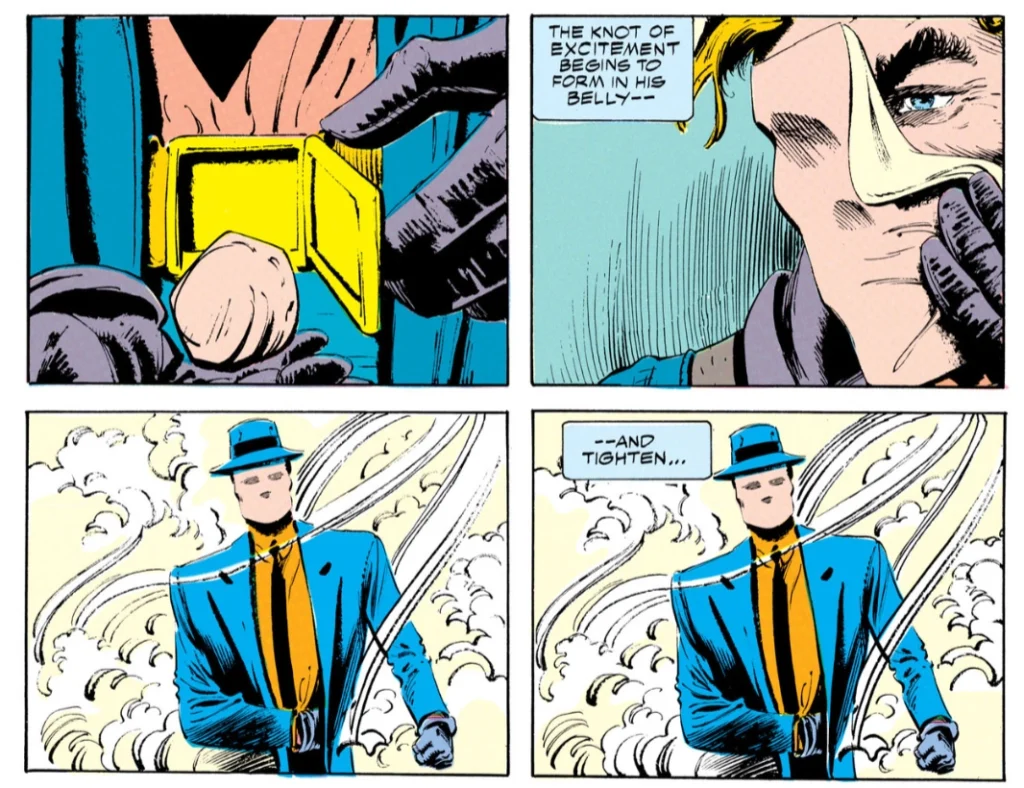

Writer Denny O’Neil and editor Mike Gold didn’t have a lot to go on when they set out to reintroduce the Question to a 1980s audience. As Gold puts it in his text introduction to The Question #1 (November 1986, cover date February 1987): “by our third issue…we will have published more pages of Question stories than Charlton did…” It seems reasonably clear that O’Neil had something a little different in mind for the character. But rather than do a hard reset, he chose to start by picking up right where the Charlton series left off, and instead put his lead character through a transformative experience over the course of the first two issues.

A new start, but not a reboot

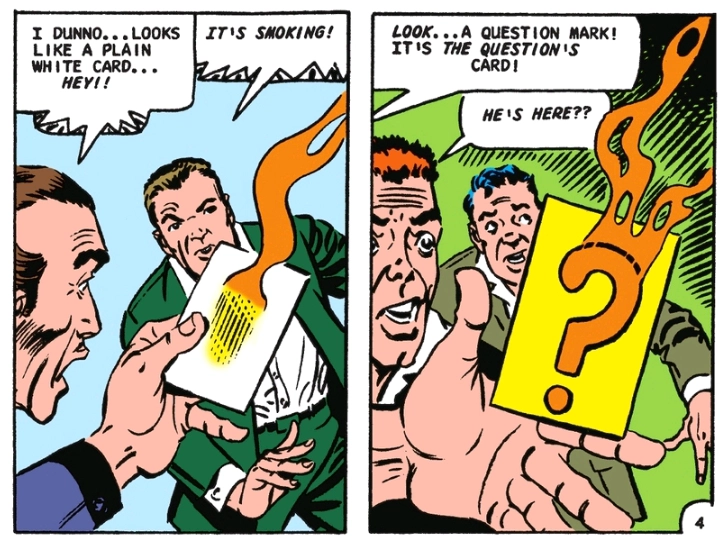

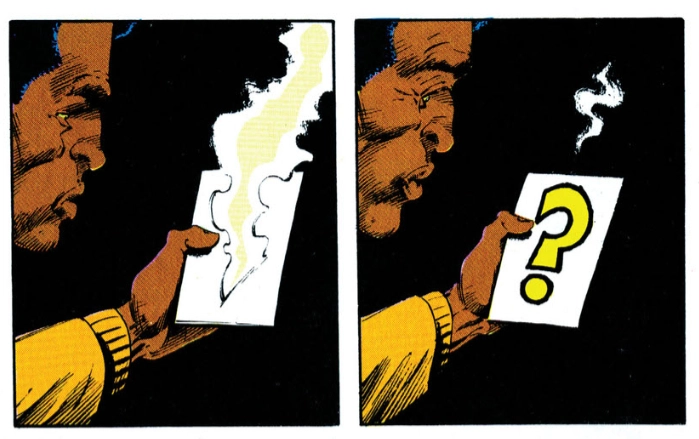

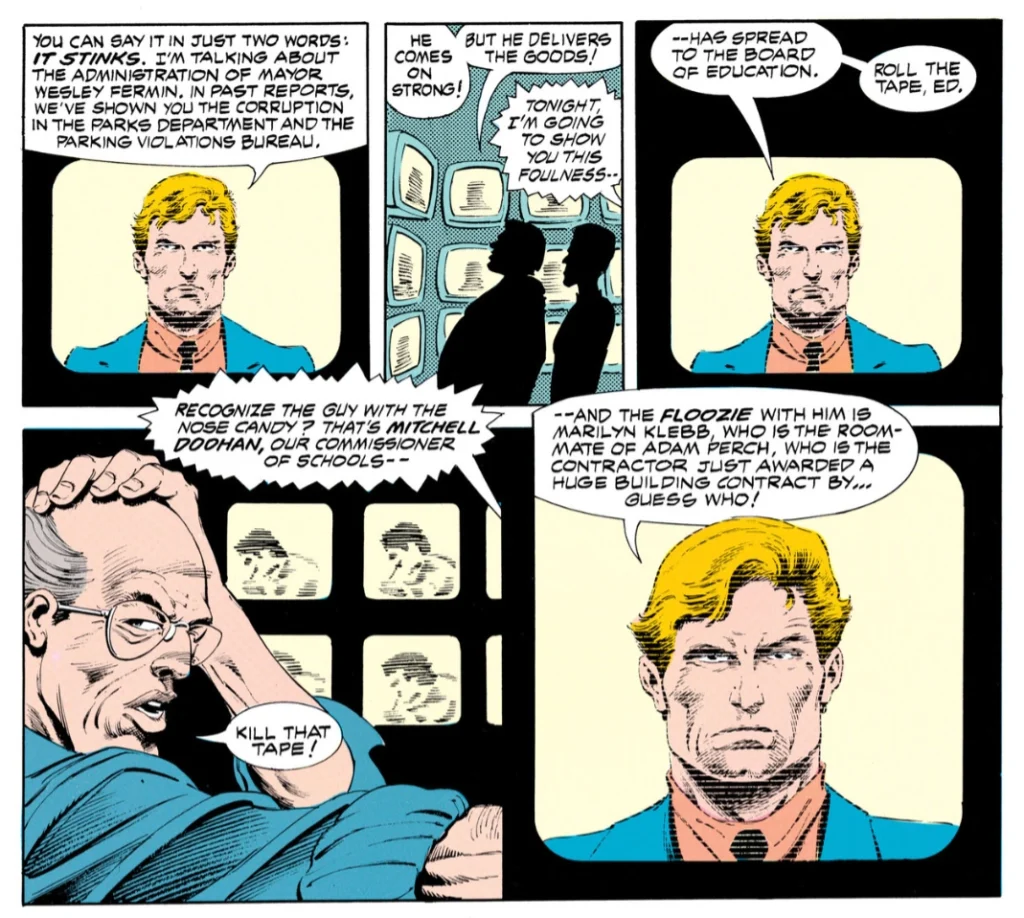

The Question #1 opens with the Charlton series’ status quo relatively intact. Television reporter Vic Sage uses his masked crimefighting identity of the Question to gather evidence for his news stories, and also to fight back against the government corruption he reports on when a more direct approach is needed. The opening scenes of the first issue are very similar to the first Question story from 1967, but our hero will soon be taken to task for his arrogance and inflexibility.

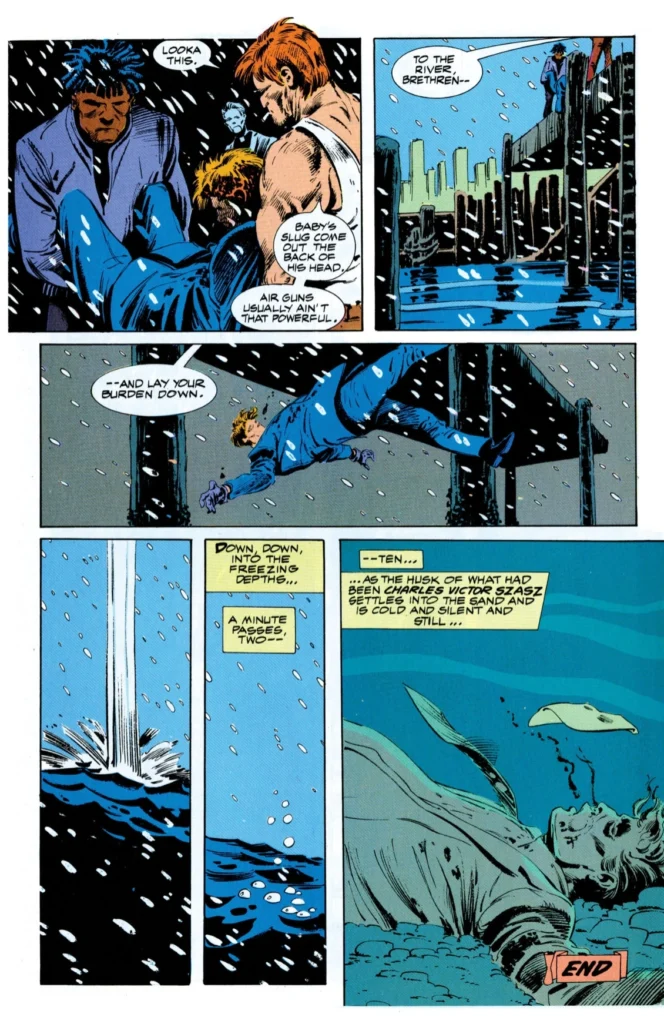

Panels from “Who is the Question?” story and artwork by Steve Ditko; and The Question #1, story by Denny O’Neil, artwork by Denys Cowan and Rick Magyar. © DC Comics.

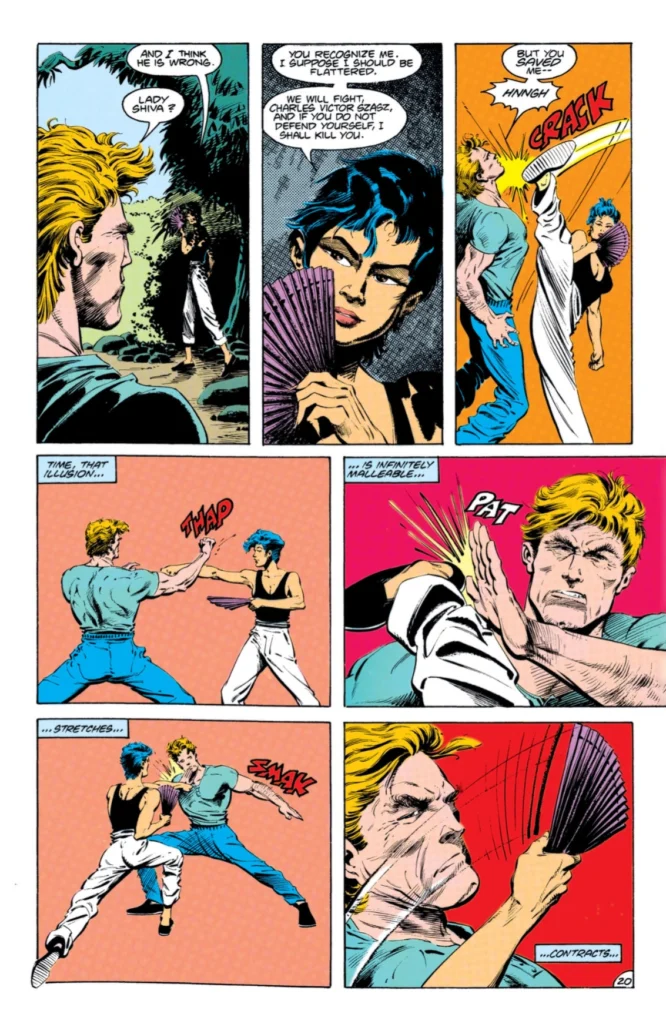

Writer O’Neil borrows a few characters from his earlier Richard Dragon, Kung Fu Fighter series to set the Question on his new path. First among these is Lady Shiva, a philosopher-assassin working for Reverend Jeremiah Hatch, the primary villain of the piece. In an early scene she stays out of the Question’s way as he brawls with some low-level street thugs, but later, under orders from Hatch, she beats him near to death and looks on as Hatch’s goons seemingly finish the job, dumping him in the river for good measure.

O’Neil does a great job with what has become a dying art: telling an ongoing narrative over a series of single issues that can all stand on their own. This was the normal (and often preferred) approach to ongoing monthly comics at the time, when trade paperback collections were uncommon, but O’Neil is particularly good at making each issue feel like both a complete story and a part of a larger saga. All of the first eight issues end on a decisive “the end,” rather than resorting to “to be continued” – he’s confident that what he is writing about is interesting enough that the monthly audience will keep coming back.

Zen and the art of crime fighting

In the following issue, Lady Shiva inexplicably fishes the Question out of the river and delivers him, battered and broken, to a remote cabin in the wilderness. Here he meets “Richard,” a wheelchair-bound mentor (this is most likely Richard Dragon, the aforementioned Kung Fu Fighter) who nurses him to health and starts him on the path to becoming a Zen warrior, or at least to a more balanced and contemplative existence.

Artist Denys Cowan’s real world martial arts expertise lends an authenticity and an elegance to the fight scenes, as the Question graduates from unskilled brawler to trained fighter.

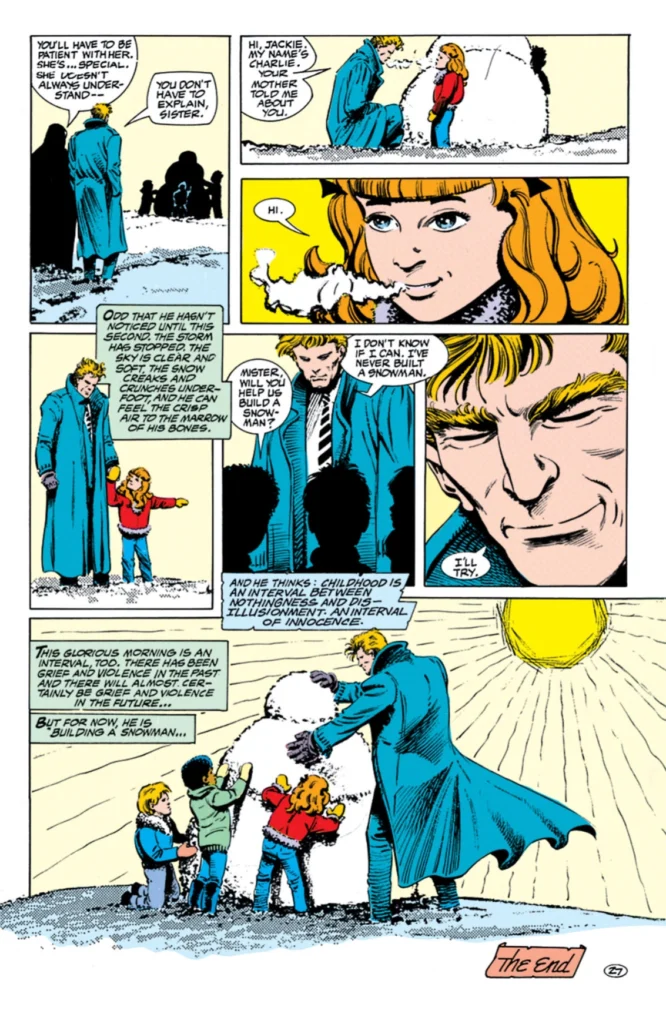

Thus the series becomes a vehicle for O’Neil to slip the occasional nugget of about Zen Buddhism and martial arts into what is ostensibly a superhero action comic with a healthy dose of hard-boiled crime. The next few issues find the Question foiling Reverend Hatch’s increasingly bizarre schemes, but also finding time for the occasional “moment of Zen,” such as building a snowman with some orphan children.

In the interest of broadening his readers’ horizons, O’Neil offered the now-legendary “recommended reading list” at the end of each issue, where he would suggest books that may have had some influence over that issue’s story, with titles as varied as Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Ed McBain’s Precinct 87 series, and The Uses of Enchantment, a well-respected work on child psychology.

The Question vs. Rorschach

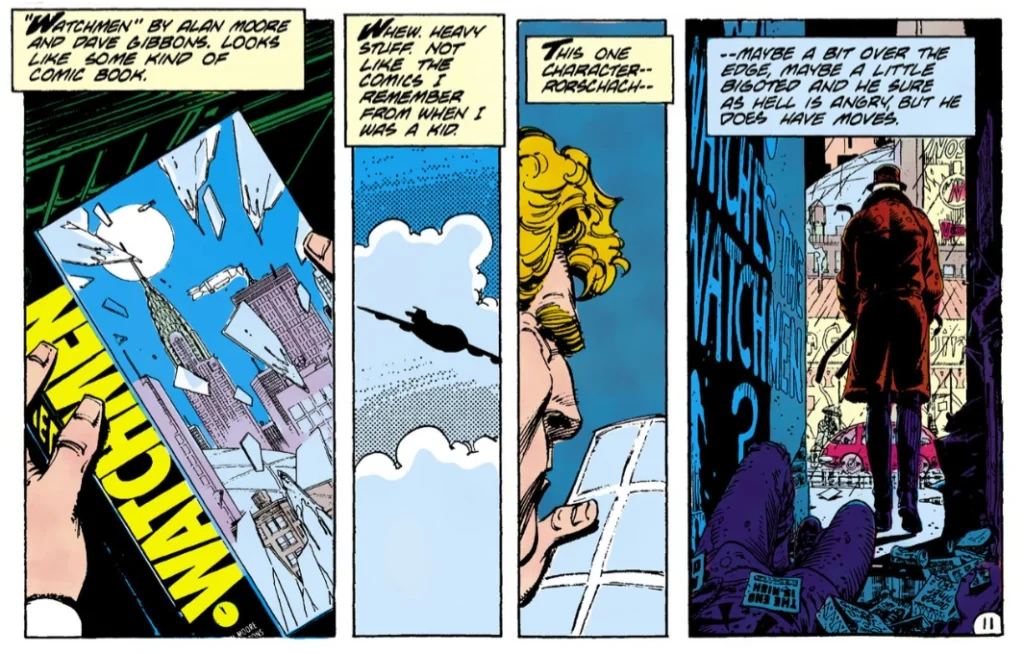

Denny O’Neil’s Question and Alan Moore’s Rorschach start at roughly the same place, but go in wildly different directions. They both begin as intense, relentless seekers of truth, but where Vic Sage has the structure of a profession to give his life order, Rorschach has a horrific childhood and lives his life almost as a vagrant, he’s so completely dedicated to his crimefighting task.

More importantly, the Question has a confidant in the form of Aristotle Rodor, his version of Batman’s Alfred. “Tot,” as he is called, is an inventor and philosopher who the Question can talk things over with, and who will call him on his BS when needed – it is in these conversations that O’Neill often slips in the philosophical points he wants to make.

Rorschach, on the other hand, has no such confidant. In Watchmen, we are privy to Rorschach’s thoughts only via his journal, which gets increasingly extreme as the series progresses, and makes it clear that he spends far too much time inside his own head. If anything, Rorschach is an illustration of what might have happened to Ditko’s original Question had he not undergone O’Neil’s enlightenment.

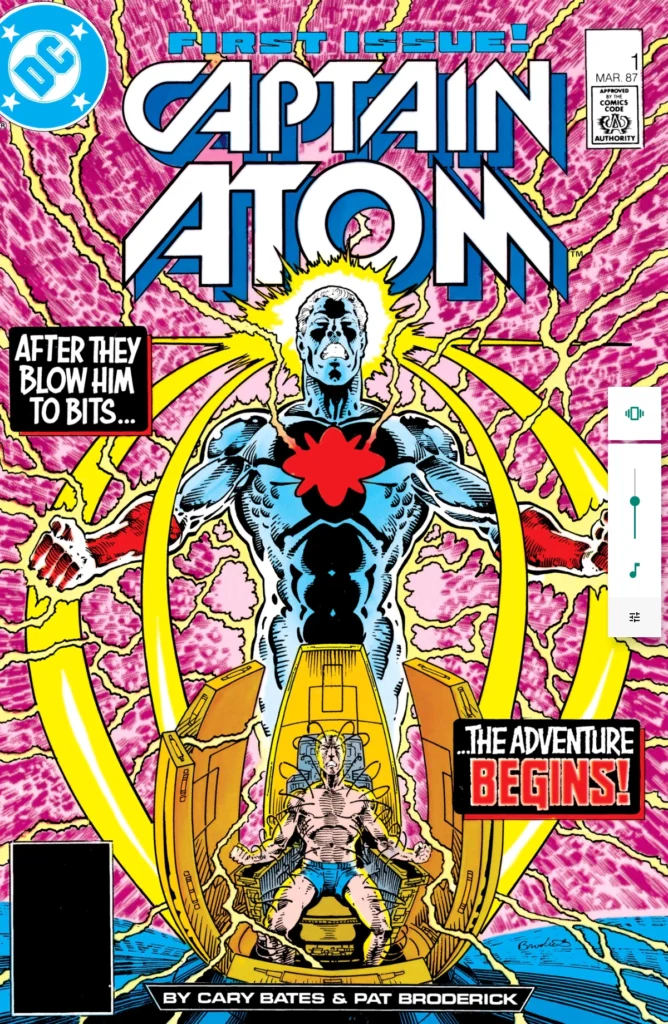

Captain Atom materializes after a false start

While Blue Beetle was the first Charlton character to appear in a DC comic book, Captain Atom beat him to having a place in the newly combined, post-Crisis DC universe – sort of. In October 1985, just as the penultimate chapter of Crisis on Infinite Earths was hitting the stands, DC Comics Presents #90 featured a somewhat bizarre team up story between Superman, Firestorm (both established DC characters) and Charlton hero Captain Atom.

On the surface, Captain Atom and Firestorm seem like somewhat similar characters, so it could be that DC felt it necessary to address any such comparisons and get them out of the way. Like Blue Beetle #1 (still a year away), this story assumes that Captain Atom has always been part of the DC universe but has been working “under the radar.” The character appears exactly as he did in his Charlton comics series, and seems to have a similar back story, all of which will be changed when the character is reintroduced in Captain Atom #1 at the tail end of 1986.

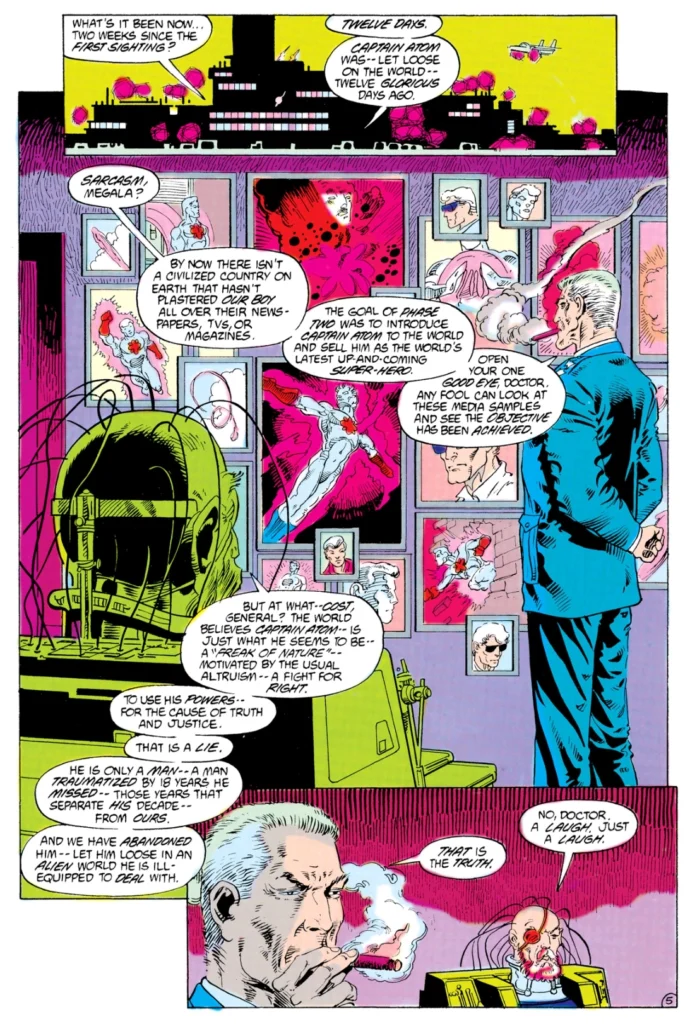

The first few issues of DC’s Captain Atom are a parade of comic book clichés: A hero falsely accused and convicted, a cigar-chomping, amoral military general, and even a wheelchair-bound mad scientist. It’s not exactly groundbreaking material, but writer Cary Bates does add one or two interesting elements to the character. Instead of accidentally being caught in a space-bound nuclear experiment as depicted in Captain Atom’s original origin story (in Charlton’s Space Adventures #33, March 1960), he is now the coerced subject of a deliberate test involving material recovered from a crashed alien spacecraft. As before, he is vaporized and later reconstitutes himself atom by atom, but this time the story adds a “man out of time” element, as Captain Atom reappears 18 years later. His wife has passed away after remarrying the very general who forced him into the atomic test in the first place, and his children are now adults.

The new series retains the idea that Captain Atom is under strict government control, and in a clever nod to the past, the cover story given to the public about where he came from is his Charlton origin story.

The Blue Beetle’s mix of Batman and Spider-Man provided textbook mainstream superheroics, and The Question tapped into the “dark and gritty” trend that would overtake much of the comics industry output in the latter half of the 1980s. But Captain Atom quietly soldiered on as a dependable mid-tier series and outlasted them both by several years.

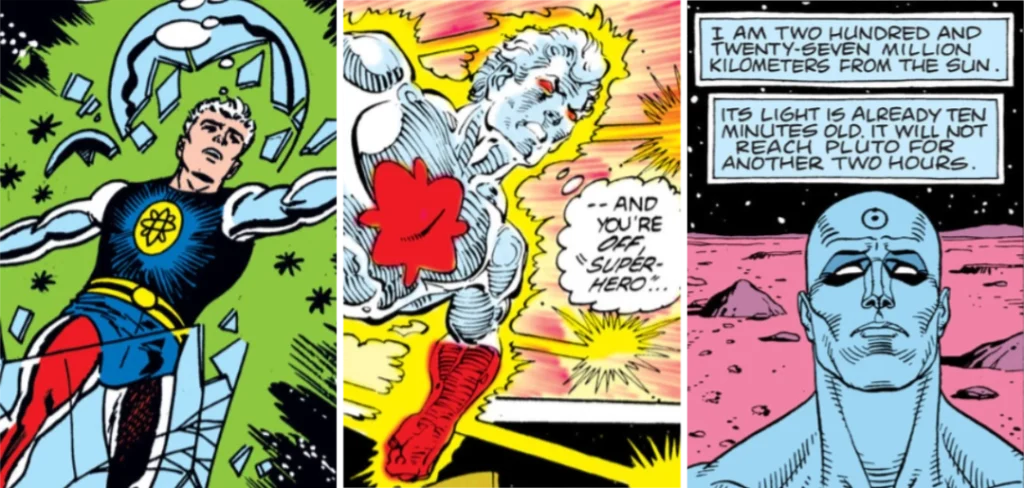

Captain Atom vs. Dr. Manhattan

Alan Moore stays fairly close to Captain Atom’s original origin story when he recounts Dr. Manhattan’s beginnings in Watchmen #4 (August 1986, cover dated December), changing a few details for the sake of naturalism and emotional resonance.

His characterization is quite different, however. Captain Atom retains a very fallible, human personality after he undergoes his transformation. But Moore’s approach is very similar to what he had been doing in Swamp Thing over the previous few years. His reasoning seems to be that any man whose perception of reality was so fundamentally transformed would lose his ability to relate to other human beings, and as a result would withdraw from earthly concerns all together.

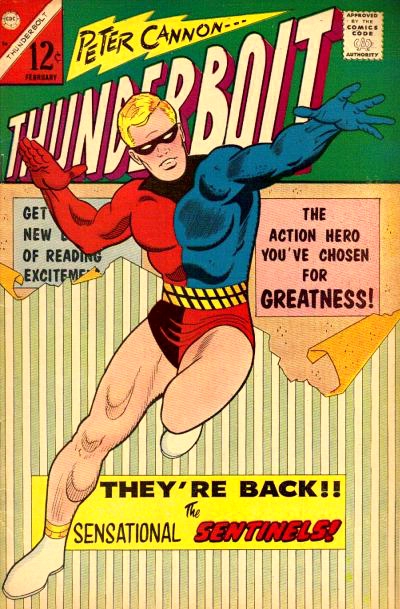

Peter Cannon, reluctant hero

Charlton’s Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt presented DC with an unusual challenge: although the character has been published by Charlton and appeared alongside their other heroes, his creator had retained ownership of the copyright. It’s unclear what the provisions were for the character’s inclusion in DC’s Charlton buy-out, but it seems that DC wouldn’t have much incentive to spend time developing a character they didn’t own.

Nevertheless, there were plans to use the character. The first of his few appearances (other than a very brief cameo in Crisis on Infinite Earths) was in DC Challenge #5 (December 1985, cover date March 1986), coincidentally illustrated by Watchmen artist Dave Gibbons. DC Challenge was what is sometimes referred to as an Exquisite Corpse – a creative challenge where a work of writing or artwork is added to by subsequent creators without knowing what the previous or subsequent contributors have in mind. In this case, each issue was done by a different writer-artist team, with the next team required to pick up the story where the previous team left off.

Due to the chaotic and unplanned nature of its storylines, DC Challenge isn’t considered to be within DC continuity, so this doesn’t qualify as an “official” appearance of Peter Cannon in the DC universe. It does, however, give a good sense of what the DC version of the character might have been like. The story is mainly a barely coherent parade of character cameos, with obscure characters like Dr. Fate and Blackhawk rushing to foil an alien invasion of New York. In Peter Cannon we meet a seemingly wealthy, aloof character , brooding in his mansion until his exotic servant convinces him to go out and use his superior physical and mental abilities to help repel the invasion.

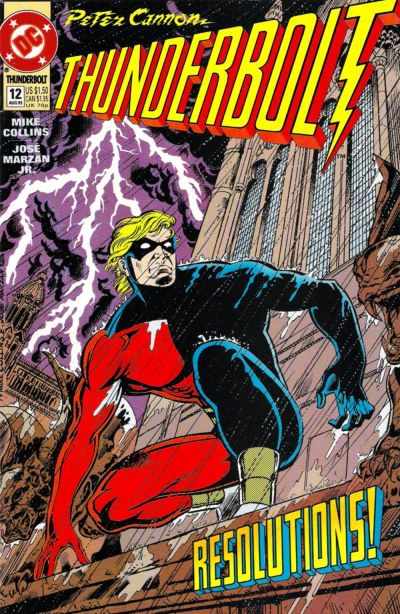

Blue Beetle and Captain Atom were appearing regularly as members of the Justice League, and The Question was teaming up with the likes of Green Arrow and Batman. But Peter Cannon didn’t manage to assimilate into the wider DC univers, perhaps due to the more complicated copyright ownership situation. Eventually, after one or two false starts, DC finally got a Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt series off the ground, which ran for a scant 12 issues between 1992 and 1993. While it’s unclear why it didn’t gain much traction or last longer, but it’s likely that it just went unnoticed in the crowded the comics marketplace of the early 1990s.

Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt vs. Ozymandias

Adrian Veidt is arguably the least changed of the Charlton heroes in Watchmen. Peter Cannon was meant to be a perfect physical specimen with advanced intelligence, and all the aloofness that would go along with that. Veidt is just that idea taken a step further, with the arrogance of a man who knows he’s smarter than everyone else, and therefore he knows what is best for the world and is prepared to justify doing whatever it takes to save humanity from itself.

Who watches the Action Heroes?

Would Watchmen have been better if Alan Moore had been allowed to use the Charlton Action Heroes as he originally planned? I don’t think so. The primary reason to do a new story with an old character is to take advantage of the easy emotional resonance and audience expectation that a familiar character brings. Moore has spent much of his comics writing career doing just that, and with great effect. “The Anatomy Lesson” in Saga of the Swamp Thing #21 stands to this day as the best example of how to change everything about a character without changing anything, and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is a wonderful intellectual and creative exercise in finding ways for disparate characters to coexist.

But I don’t think the Charlton characters would have brought a sufficient level of familiarity to Watchmen’s readers. The comics audience was growing exponentially in the 1980s, and it doesn’t seem likely that all that many of them would be familiar with a fairly obscure group of characters whose heyday had been almost 20 years earlier. Plus, the changes Moore had to make in order to make the Charlton heroes fit the story he wanted to tell are pretty extreme – it seems likely that long term fans would be upset more than intrigued. Worse still, if Watchmen might not have been nearly as accessible if it had come with a cast of pre-existing characters but largely unfamiliar characters.

Although I don’t think Moore had a choice in the matter, creating new characters for Watchmen was clearly the right call, even if they were heavily based on the Charlton heroes. The book was clearly the better for it, and so were Blue Beetle, the Question, and the others who escaped obscurity to become important parts of DC’s storytelling machine.