As a kid I never really had much time for Superman.

The character is so ingrained in western culture that I couldn’t tell you when I first became aware of him. It may have been the Super Friends cartoon series, which I remember watching (but not particularly enjoying), but it could just as easily been a picture on a paper plate or bottle of bubble bath.

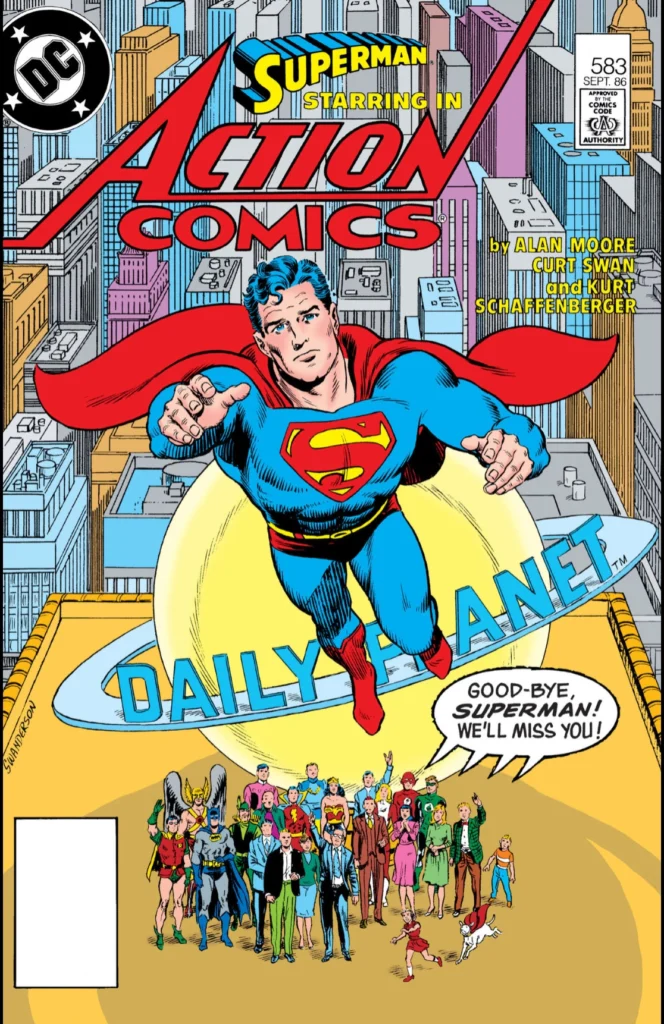

Certainly, the first Christopher Reeve film in 1978 would have raised Superman’s profile considerably, especially with the Marlon Brando prologue’s attempts to make it more Star Wars than Adam West Batman. It’s a wonderful film, but it gets by largely on the incredible charm of its cast, something that was completely missing from the Superman comic books of the time. It’s possible that I leafed through issues of Action Comics or Superman in the early ‘80s, hoping to find some of that same charm, but I found the stories to be stiff and humorless when they weren’t outright silly. Even Alan Moore’s “farewell” story in Superman #423 and Action Comics #583 left me cold, being an exercise in nostalgia for a version of the character that had failed to engage my interest in the first place.

That all changed in 1986. Like a substantial portion of the comic book audience of the time, I was a massive John Byrne fan. His stellar work for Marvel on X-Men and Fantastic Four had made him one of the most popular comics creators in the industry, and now he was jumping ship to DC in order to bring Superman in line with the more modern sensibility that was sweeping comics at the time. I was excited to see what he would do with it, but honestly, if Byrne had been taking over The Flash, Wonder Woman, or even Space Cabbie I would have been there for that too. I still didn’t really care about Superman, but it was JOHN BYRNE.

Don’t call it a reboot

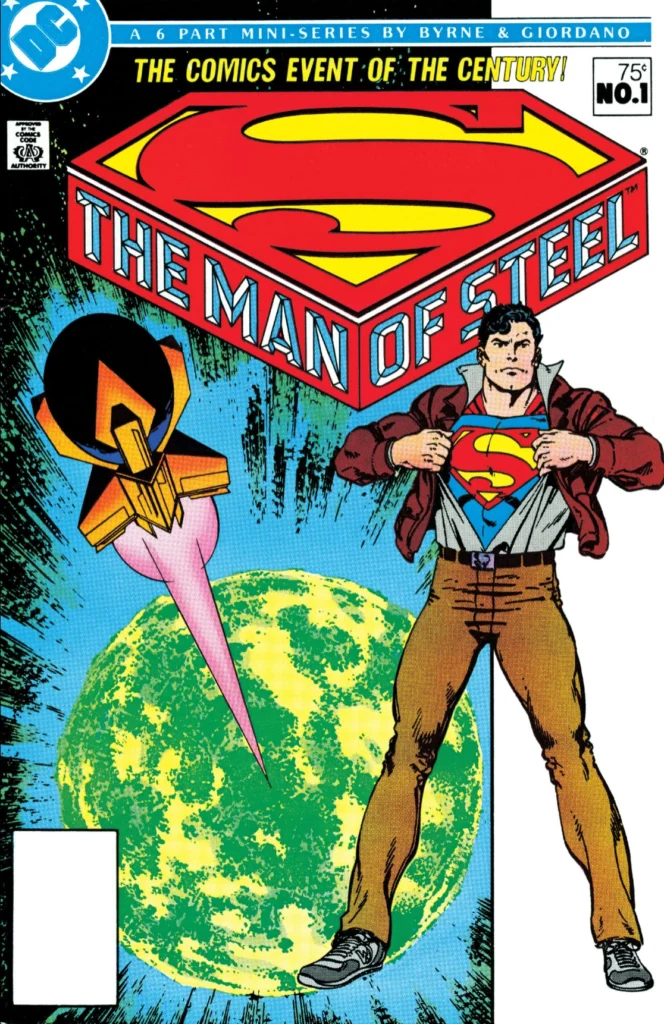

John Byrne’s takeover began with The Man of Steel, a six issue, biweekly miniseries that would retell Superman’s origin. Byrne’s goal was to strip away all the convoluted continuity that had attached itself to the character and get down to basics. Gone would be a lot of the silly or extraneous recurring characters and situations, such as the multitude of other survivors of Krypton (sorry, Krypto), an arctic fortress filled with weird trophies, or Lois Lane’s bullish obsession with finding out Superman’s secret identity.

Byrne has said that he thought the 1978 film took the right approach (interviewed by Jon B. Cooke in 2006 for Modern Masters Volume 7: John Byrne, TwoMorrows Publishing), and the first issue of Man of Steel follows a similar structure. The story opens on the planet Krypton, a high-tech but cold and lifeless world on the brink of disaster. Byrne demonstrates his talent for exposition, getting out all the necessary back story in the space of a few pages of conversation between Jor-El and Lara, Superman’s parents.

To his credit, while he was clearly inspired by the film, Byrne makes the familiar story his own. His designs for the look of Krypton aren’t like anything we’ve seen before, and he manages to keep to the basics of the traditional Superman origin while also making it seem fresh.

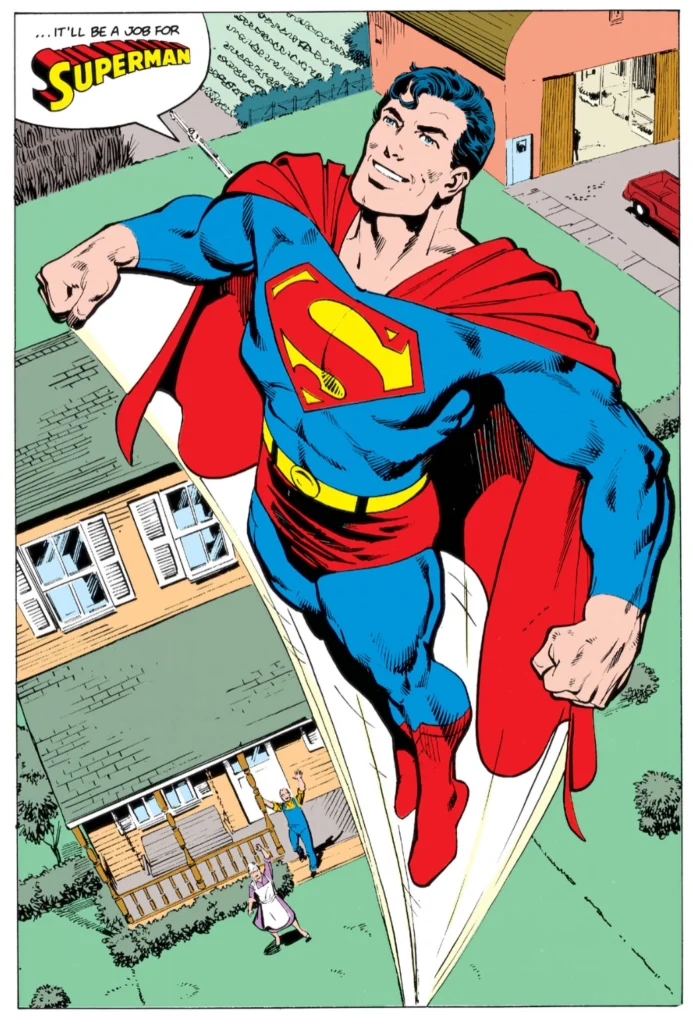

The story jumps ahead to Clark Kent as a teenager. In this version he’s a star high school football player, much to the disappointment of his adoptive father. Their conversation establishes the core of Superman’s character – his basic decency – as he realizes that using his enhanced physical abilities to excel at sports isn’t really fair to the other players. This sets him on his journey to help people wherever he can. At first he is able to operate anonymously, but eventually his heroics are exposed to the public, requiring the creation of a costumed identity that will allow him to maintain a private life.

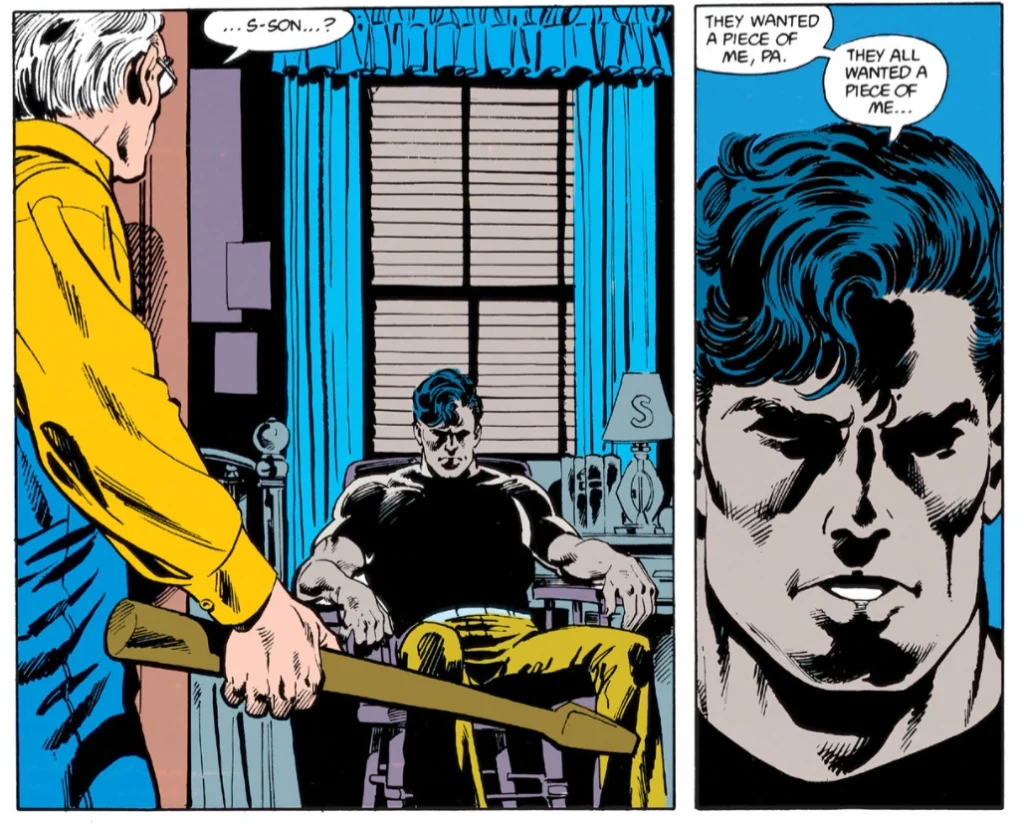

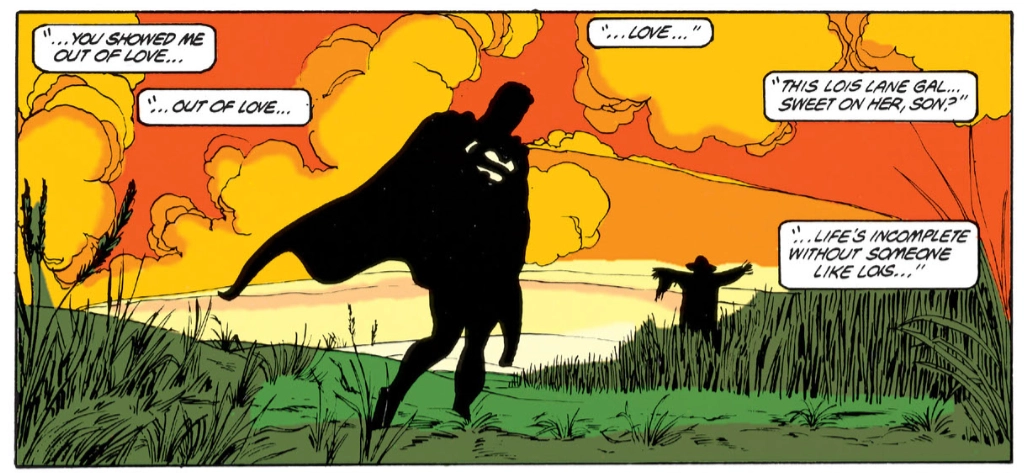

Byrne avoids the 1978 movie’s pile-up of tragedy by keeping Clark Kent’s parents in the picture, not just still alive but a vital part of the supporting cast. Later in the series, his trips home, and ability to talk to his parents in confidence about his life as both Clark Kent and Superman, serve to add a great deal of humanization and depth to the character.

Finding his place in the world

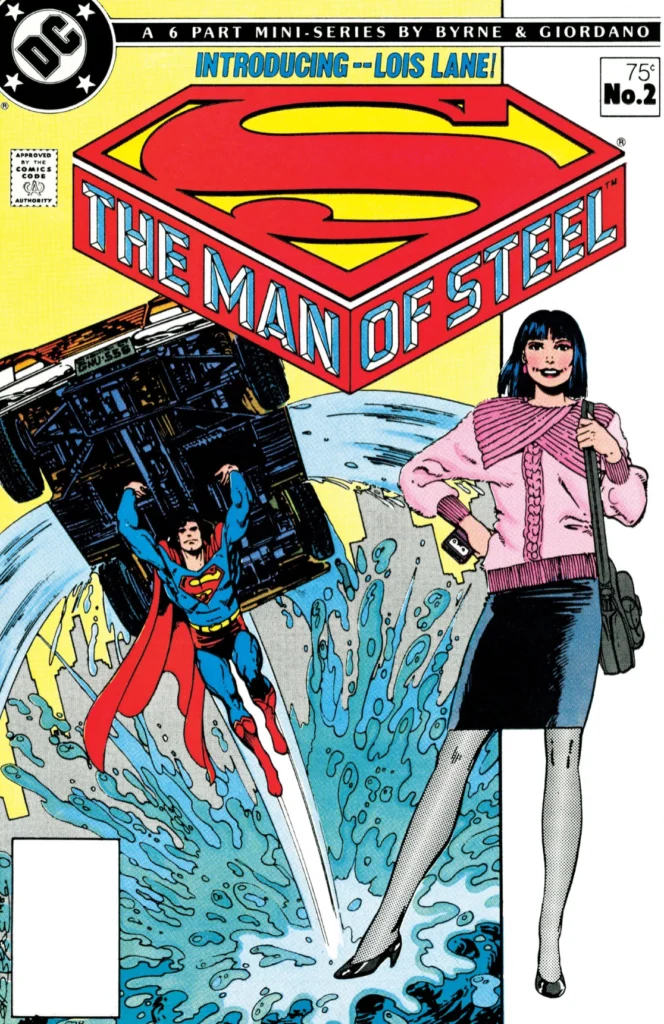

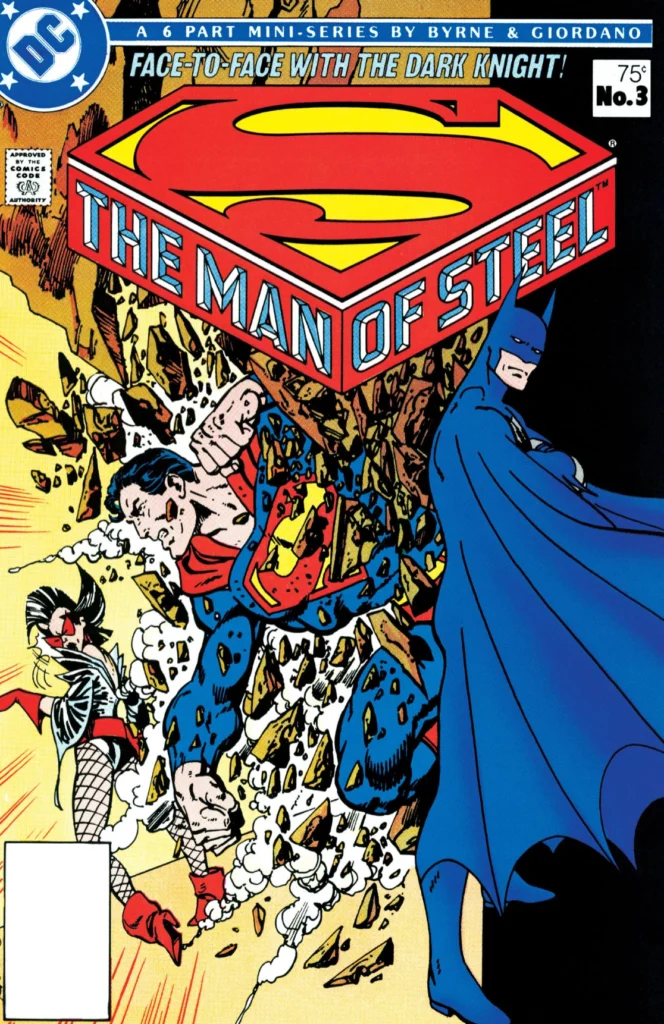

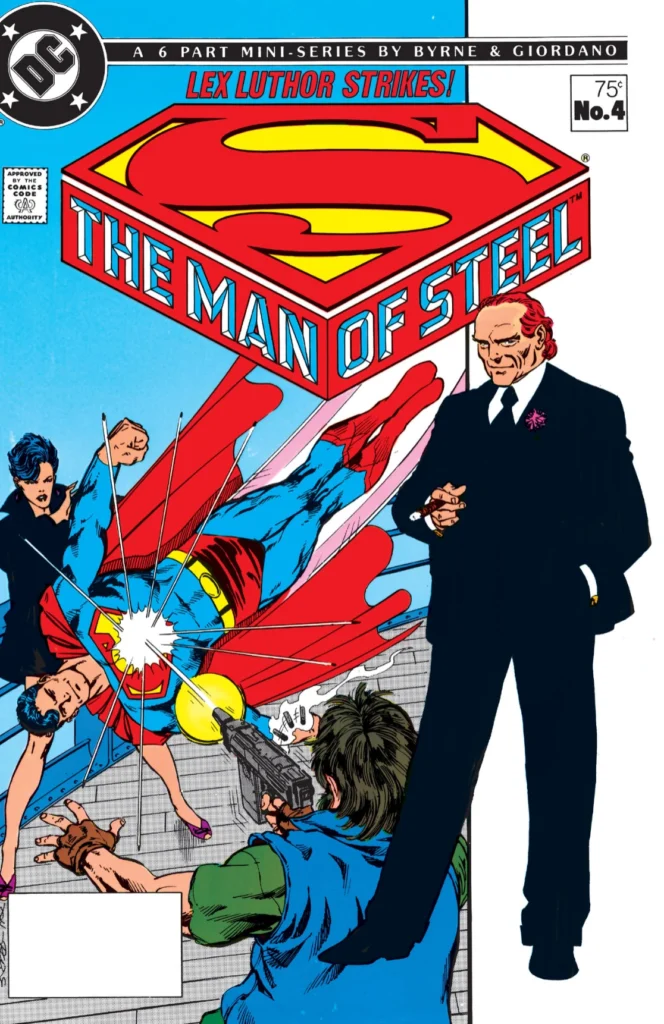

John Byrne reintroduces Lois Lane, Batman and Lex Luthor in The Man of Steel issues 2, 3 and 4. © DC Comics.

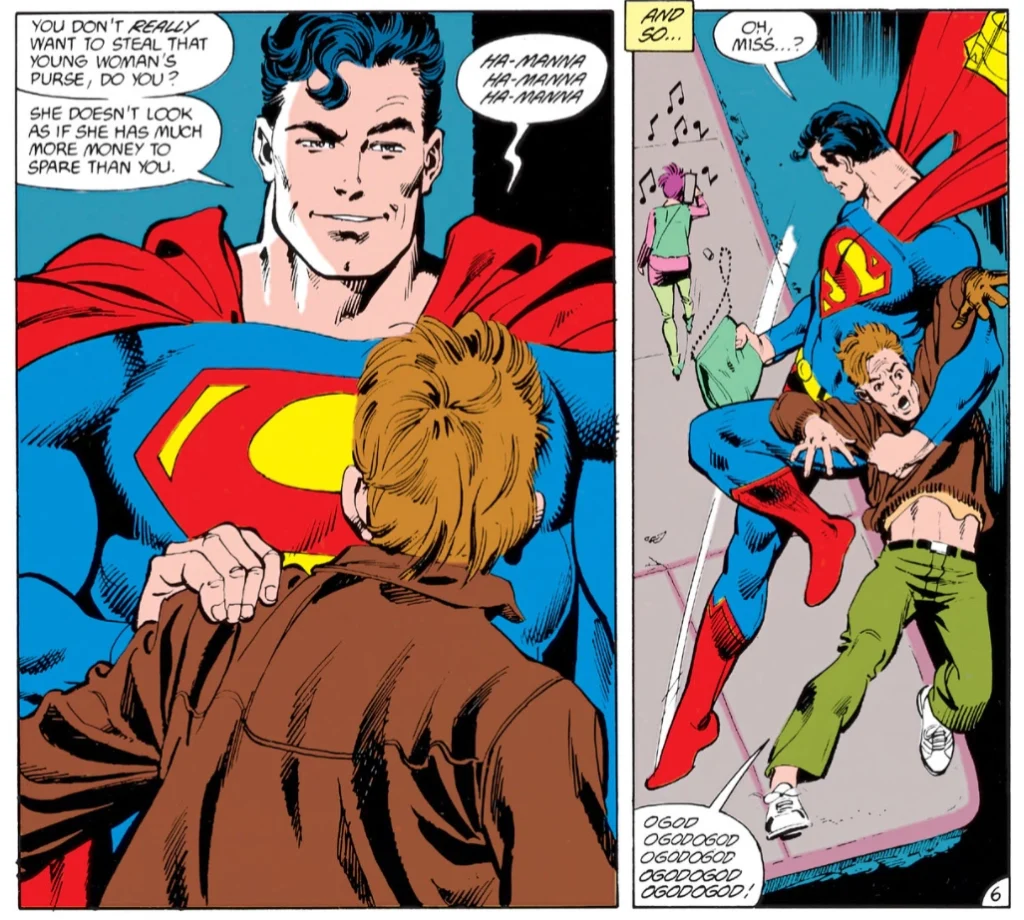

The Man of Steel #2 establishes Superman’s presence in Metropolis, and reintroduces some of the supporting characters such as Lois Lane (who we briefly met in issue 1) and Perry White, editor of the Daily Planet newspaper where Clark Kent will soon find himself working. The issue also takes another page from the 1978 film as we get a slightly humorous montage of Superman foiling crimes and rescuing people, and their often comical reactions to his abilities. In addition to the superheroics, this sequence gives us a good sense of Superman’s affable personality and gentle sense of humor – miles away from the stiff, out-of-touch characterization of the recent past.

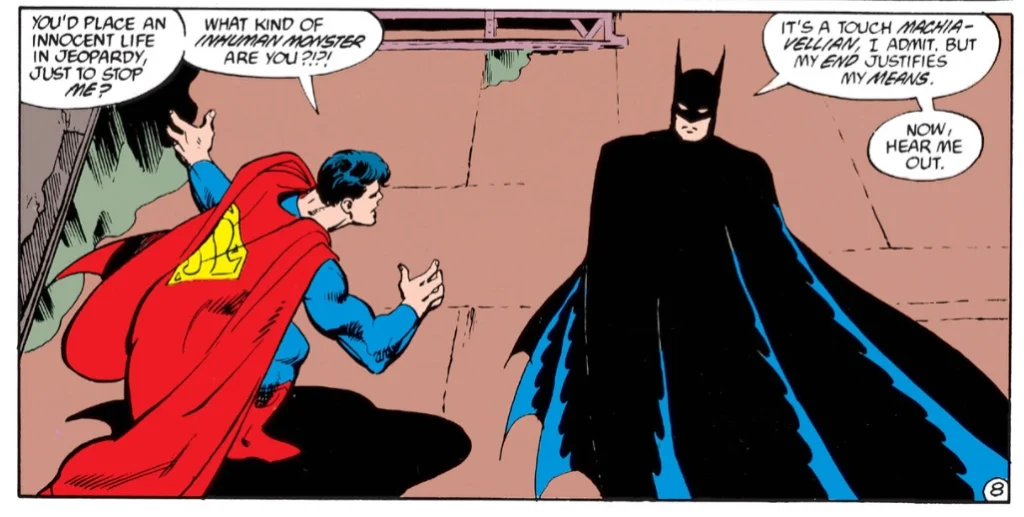

Issue 3 features a guest appearance by Batman, but it’s really a Batman story with a guest appearance by Superman. The story’s structure is a template for what Byrne will be doing in Action Comics: each issue a team-up story featuring Superman, told from the point of view of the guest character. The goal of the story seems to be to introduce Superman to a bit of the wider DC universe, but also to illustrate the differences between Batman’s ruthless crimefighting techniques and Superman’s more “in the light of day” approach. The story also establishes that, far from the close friends they had been in the previous continuity, Batman and Superman would now be keeping each other at arm’s length.

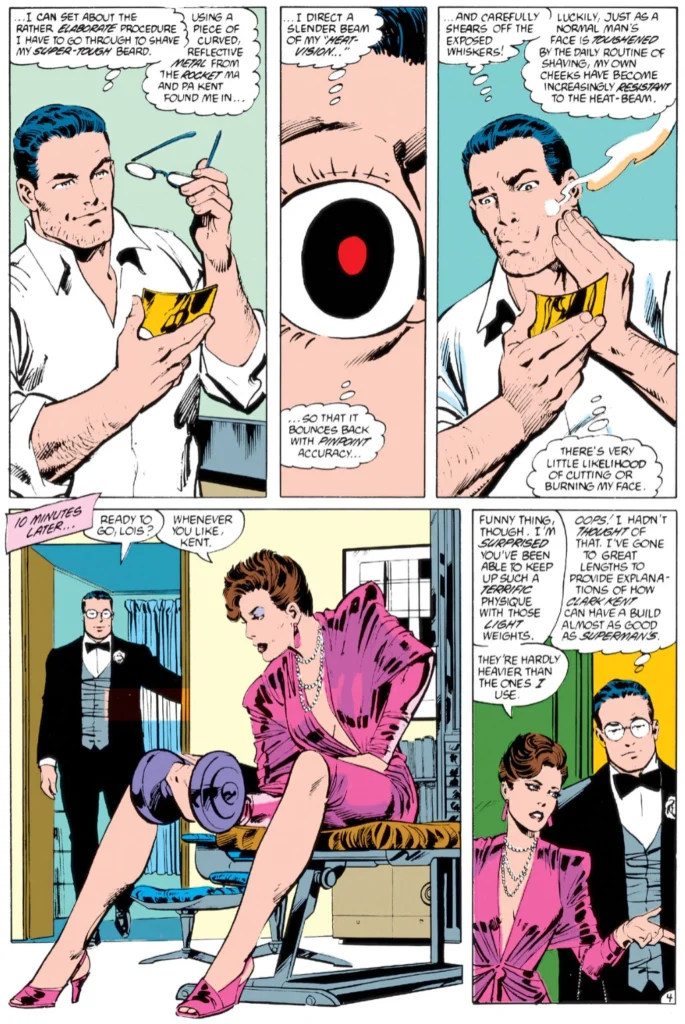

In The Man of Steel #4, we see quite a bit more Clark Kent than we have so far, and this is one of the areas where Byrne steers clear of the 1978 movie’s approach. Rather than a reedy-voiced nerd, Byrne’s Kent is a cool guy, at least by the standards of the 1980s – he’s career focused, good humored, and a snappy dresser to boot. He even works out, or at least pretends to in order to explain why he’s built like a superhero.

In giving us a glimpse of Clark Kent’s private life, Byrne also takes the opportunity to answer that burning question on everyone’s mind: how does Superman shave?

Bring on the villains

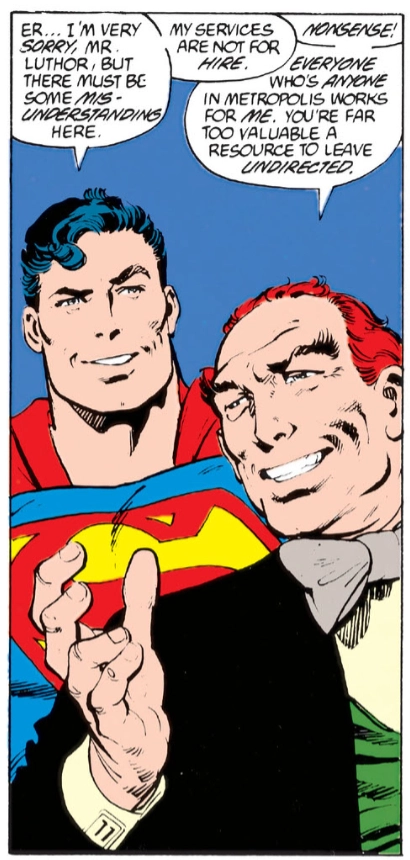

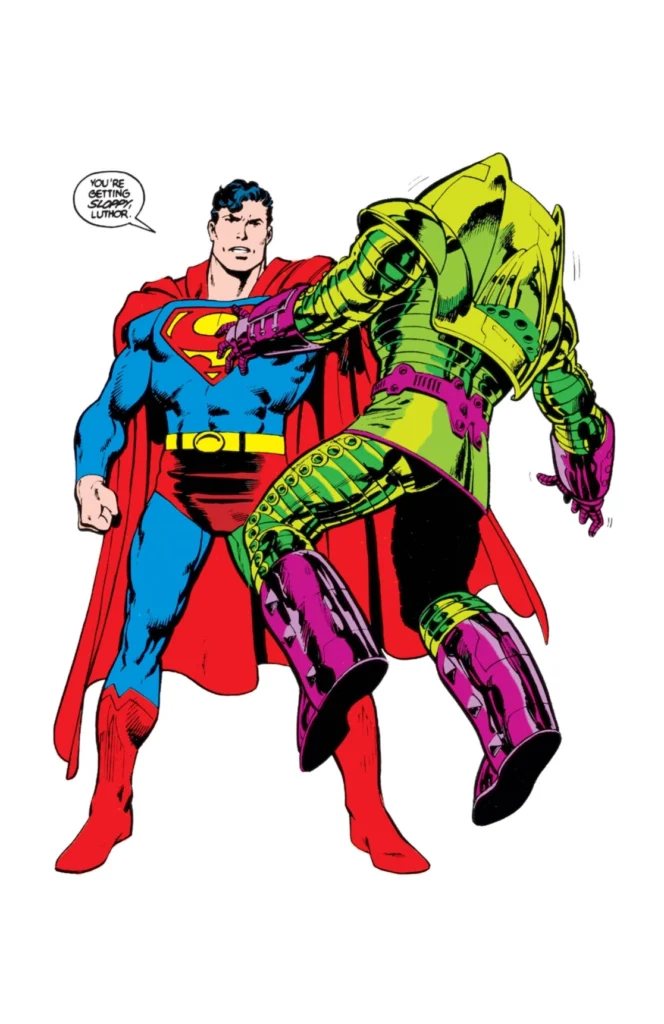

The real meat of issue 4’s story, however, is the reintroduction of Superman’s arch enemy, the villainous Lex Luthor. This is probably the biggest change from Superman’s previous status quo – in a stroke of brilliance suggested by DC writer Marv Wolfman (as mentioned in Byrne’s text piece in Superman #1, cover date January 1987), Luthor is no longer a criminally insane mad scientist in a purple leotard. He has evolved into a ruthless business tycoon, driven to distraction by all the attention Superman’s arrival in Metropolis has diverted from him.

Luthor the untouchable billionaire is the perfect foil for Superman – he presents a problem that can’t be solved with super-strength or heat vision. At the same time, Superman is an unacceptable obstruction to Luthor’s worldview, a man so fundamentally decent that he can’t be bought or intimidated into going away. This change in Luthor’s character was so utterly successful and made so much sense that it has become the standard for every new version of the Superman story, across all media, ever since.

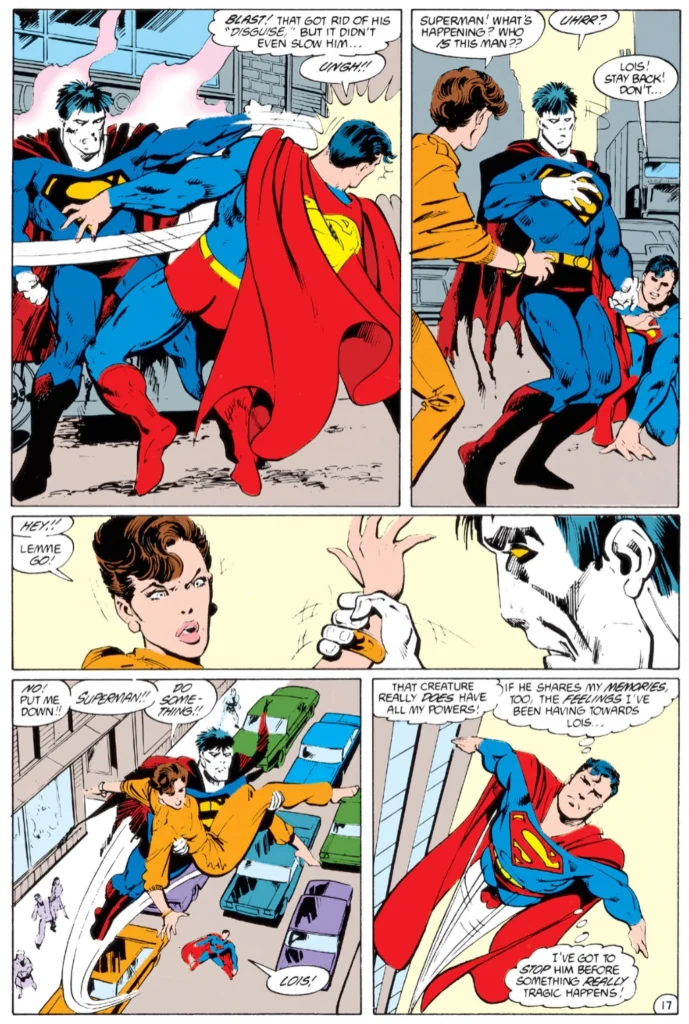

Compared to his contemporaries such as Batman or even The Flash, Superman’s gallery of villains has left a lot to be desired. Apart from Lex Luthor, most of them have ether been to preposterously powerful, too silly, or both. So it’s interesting that the first villain other than Luthor that Byrne chooses to reintroduce is perhaps one of the silliest of them all, Bizarro, a failed clone of Superman who does everything backwards and eventually moves to a square-shaped planet with a whole population of Bizarro-clones. It’s even more interesting that Byrne, after a fun fake-out gag using a callback to Luthor’s armored battlesuit days of the early 1980s, more-or-less sticks to the original story from Action Comics #254 (July, 1959).

Luthor attempts to make a clone of Superman for his own nefarious purposes, a scheme which of course goes disastrously wrong. Byrne lends the tale a much more naturalistic tone, with the clone attempting to insert itself into Clark Kent’s personal life even as its condition deteriorates. The tale even ends with a similar conclusion to the original, that Bizarro isn’t actually evil, and Byrne even gives him a much more heroic ending than the usual silly gags that the character was formerly used for.

Moving forward

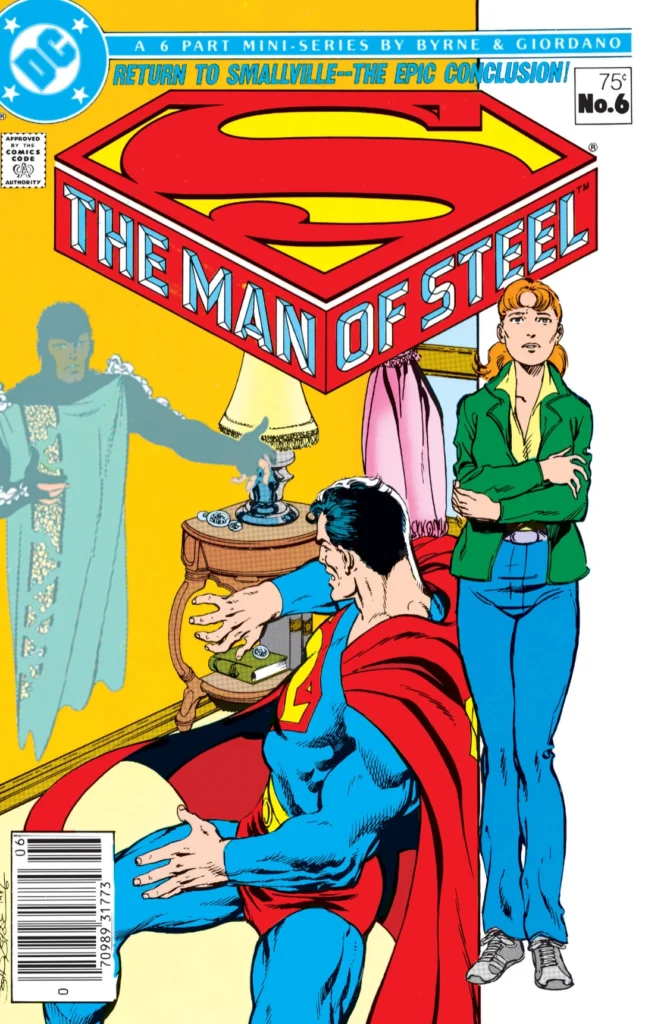

The final issue of The Man of Steel is a bit anticlimactic, serving mainly to wrap up the origin retelling and set up a few plot threads for the forthcoming Superman ongoing series. Byrne is normally very good at handling large chunks of exposition, but this entire issue is talking head conversations and Superman’s internal monologue, with very little in the way of action. It’s not terrible, but it does strain the technique to near breaking point.

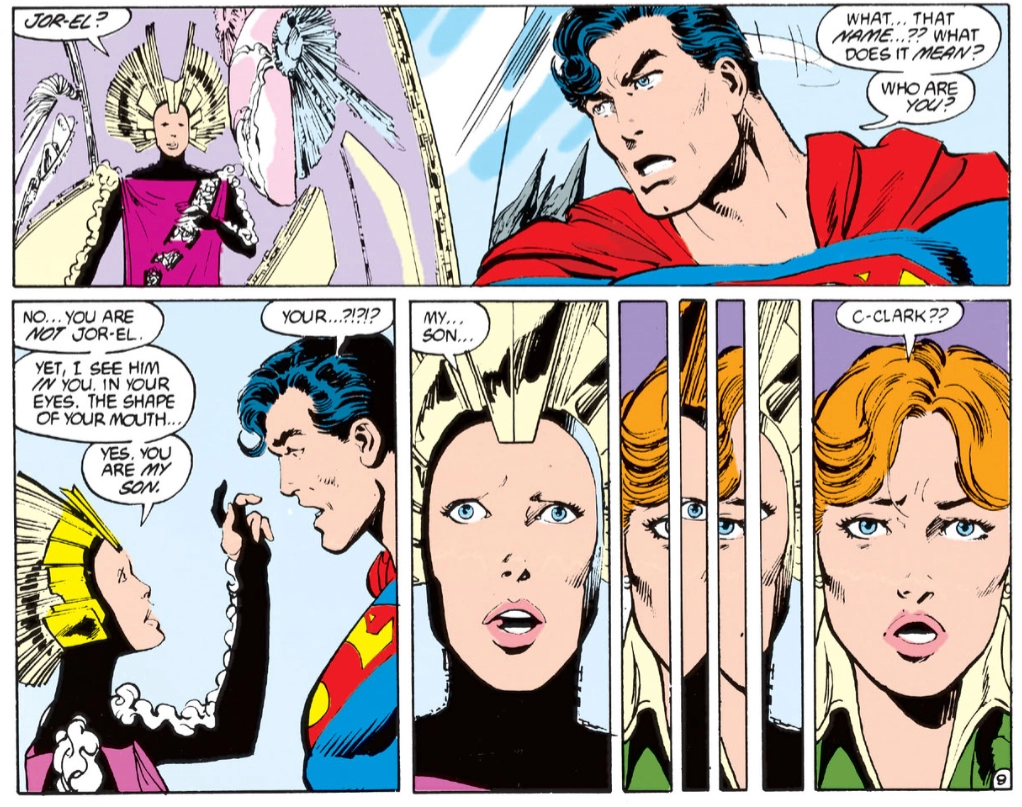

Superman is made fully aware of his Kryptonian heritage by way of a hologram of his birth father, Jor-El. However, the presence of said hologram is something of a mystery, as another major sub-plot of this issue is the disappearance of the Kryptonian rocket that carried baby Superman to Earth (a thread that will be picked up shortly in Superman #1). So where did the hologram come from? It’s a rare moment of brushing under the rug for Byrne, whose plots are usually pretty airtight.

The other major plot element is the reintroduction of Lana Lang, Clark’s childhood sweetheart who also has a part to play in an upcoming storyline. Lana’s inclusion here makes sense since the story is about Clark Kent returning home to visit his family, but at the same time a lot of the material with he ris an extended flashback that might have fit better in issue 1.

With this retelling of the origin story completed, Byrne moved right into Superman #1, which reintroduced Kryptonite, the final crucial element of the Superman mythos that hadn’t been touched on yet. With Superman’s critical weakness back in place, issue 2 firmly established that Byrne’s stewardship would not be falling back on what was possibly the most over-used trope of the previous 50 years: attempts by both friend and foe to discover Superman’s secret identity.

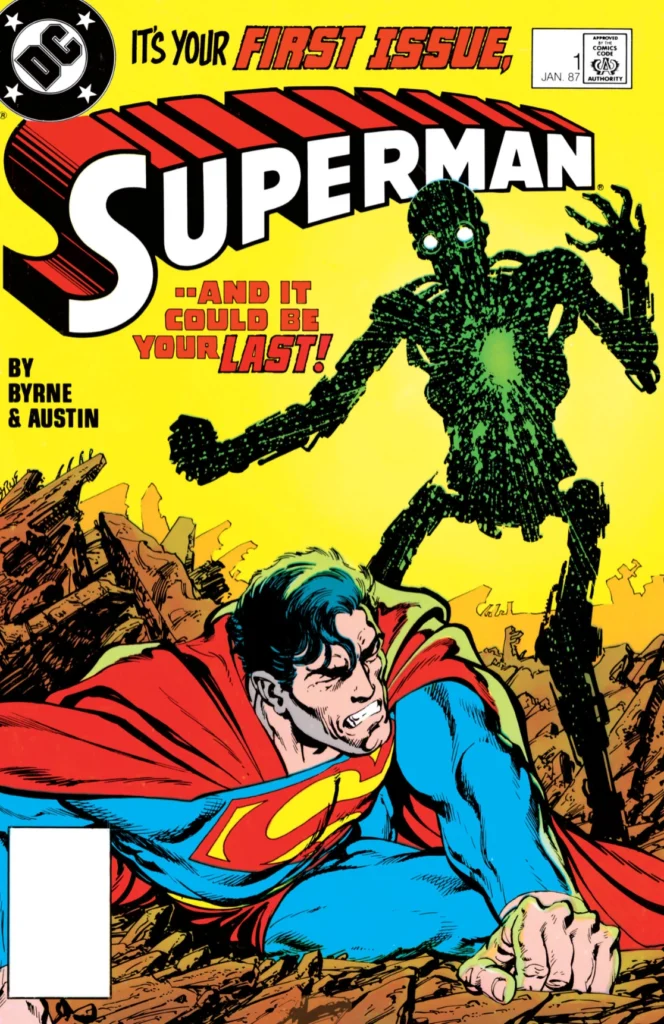

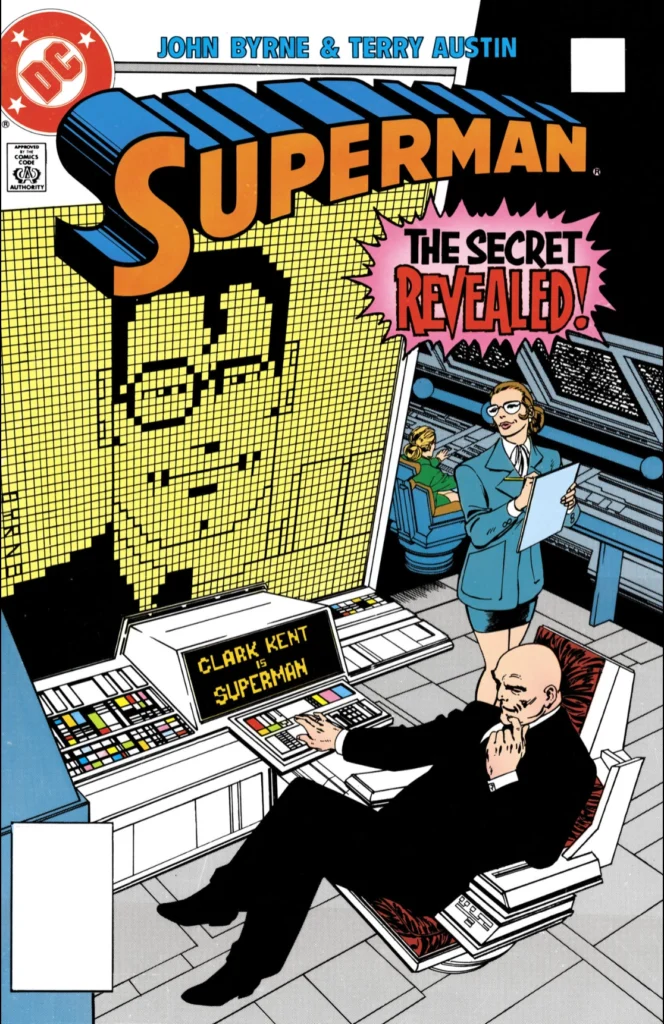

Superman (1986) issues 1 and 2 cover art by John Byrne. © DC Comics.

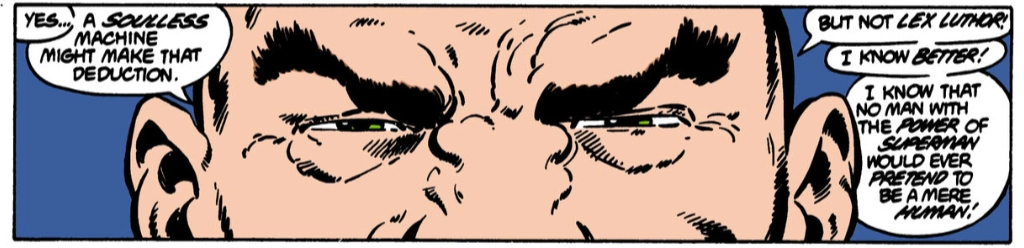

Byrne had discussed in various interviews and text pieces that he never really understood why anyone would come to the conclusion that Superman even had a secret identity. It does strain credibility that someone like Lois Lane, an intelligent journalist who spends a huge amount of time around both Superman and Clark Kent, wouldn’t put two and two together if she had any reason to believe that Superman went out among the public in disguise. Byrne drives the point home in Superman #2, a great little story in which Lex Luthor, when presented with clear evidence that Clark Kent and Superman are one and the same, simply refuses to believe it. I was so taken by this story at the time that I wrote in to the letters column praising it, and my letter was even published in Superman #6!

So what changed my mind?

How did John Byrne change my mind about Superman? Well, for a start, you would be hard pressed to find anyone better at doing superhero stories. Certainly not in the 1980s, possibly not ever. Sure, Alan Moore brought the deconstructivism, and Frank Miller brought the noir sensibility, but for straight up tales of superhero advenure, John Byrne just could not be beat.

His draftsmanship was flawless, and his command of anatomy and perspective were unmatched. You rarely, if ever, saw any of the errors other comic book artists would make that took you out of the story. He regularly varied his page layouts and camera angles to keep the storytelling fresh and dynamic, to the point that he could usually make even the most mundane conversation scene look interesting.

In addition to that technical perfection, his artwork had a warm expressiveness to it. You can see it in the faces of Ma and Pa Kent, or in Clark’s flailing attempts to flirt with Lois.

Byrne’s writing matched his artwork in the precision of his plots (usually), and he had a terrific sense of how to string individual, self-contained page stories together to form a larger narrative. The nature of the corporate owned characters he was working with meant that he couldn’t do much as far as character development, but he did his best, populating his stories with unique and expressive characters.

John Byrne gave Superman a personality that made him into a relatable character, where previously he was often a two-dimensional plot device. He brought Superman down to earth, and made his fundamental decency real and believable. He certainly made me believe that there was a human being behind all those fantastic abilities, and that he was a hero in spite of his super powers, not because of them.

It was an approach to the character so obviously spot-on that just about everyone doing Superman, whether it’s in comics, on TV, or in the movies, has been using elements of it ever since.