Frank Miller finished off what was arguably the most groundbreaking and exciting year for any comics creator with Batman: Year One, a four-part story appearing in DC’s regular Batman title. Page for page it’s less than half the length of The Dark Knight Returns, but Batman: Year One would prove to be quite possibly the most influential Batman story of all time. Writers, artists and filmmakers have been drawing on its approach to the character ever since.

Meanwhile, Miller also wrapped up Elektra: Assassin and with it his astonishing collaboration with superstar artist Bill Sienkiewicz.

October 1986

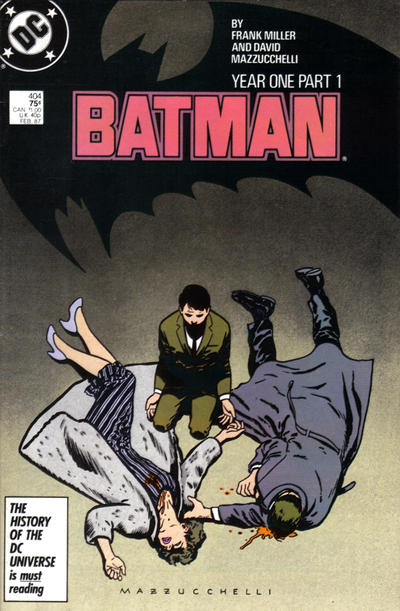

Batman #404 “Year One Chapter One: Who I Am. How I Came to Be.”

Story by Frank Miller; artwork by David Mazzucchelli; color by Richmond Lewis; lettering by Todd Klein

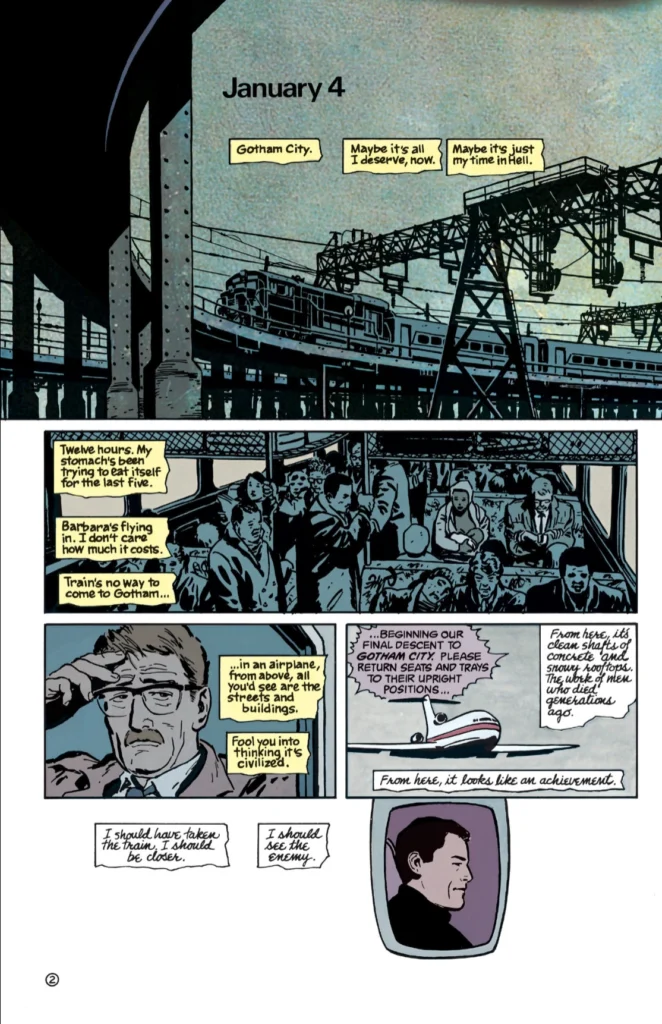

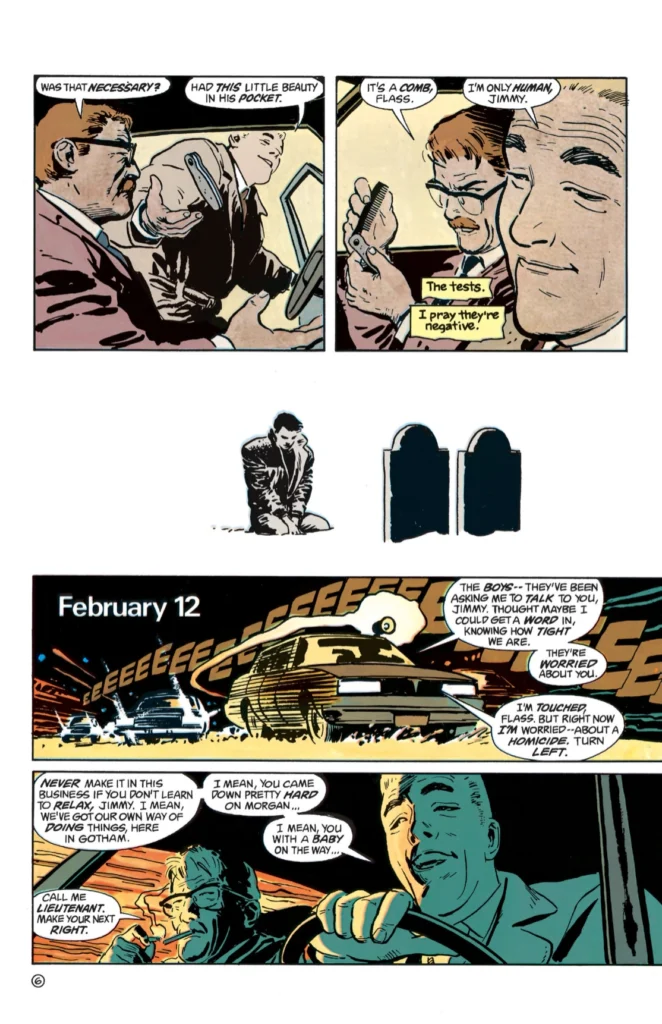

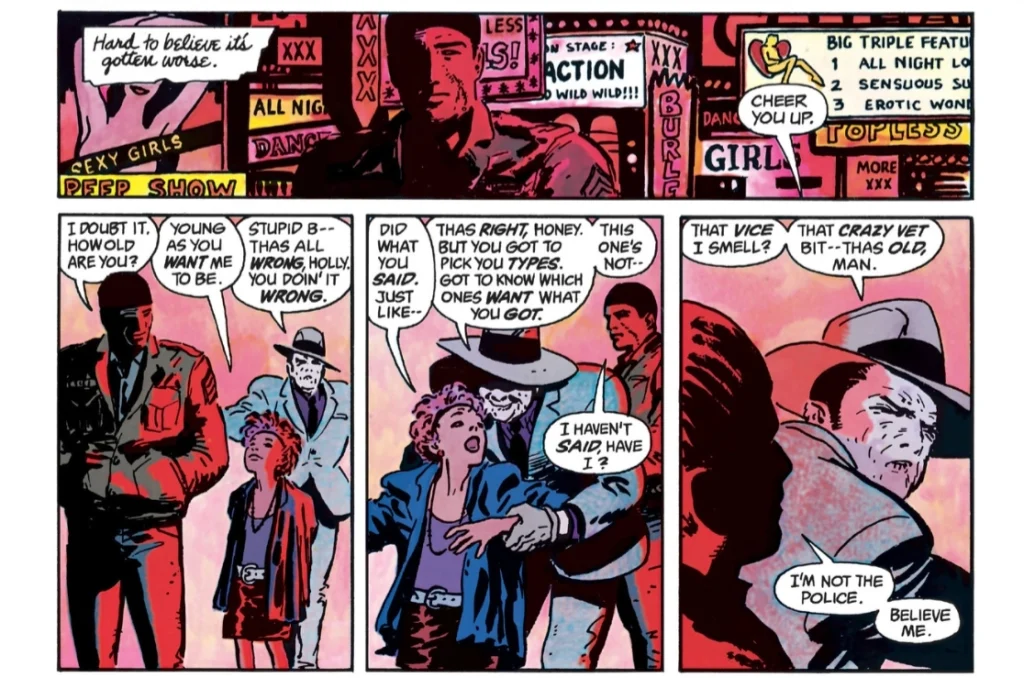

In keeping with the idea that this story will delineate Bruce Wayne’s first year as Batman, Miller adopts a loose “calendar” structure, with month-and-day headings to denote scene breaks. The opening pages establish that Miller will be emplying his tried and true method of using multiple narrators to tell the story. In this case it’s Jim Gordon providing Miller’s customary world-weary tone, while Bruce Wayne’s internal monologue shows him from the start to be completely focused on his crime-fighting mission, his intensity bordering on obsession.

The narrative jumps back and forth between Gordon and Wayne, both newly arrived in Gotham City (in Wayne’s case, after several years away), both highly competent individuals embarking on the same mission.

Mazzucchelli’s artwork is considerably more fluid and expressive here than it was in Daredevil. He appears to doing the majority of his inking with a brush rather than a pen, sacrificing sharp detail in favor of a high contrast, almost cinematic approach that complements what Miller is trying to do with the writing.

The opening pages deftly illustrate the difference between the two main characters. Gordon is shown in cramped offices or crowded into a patrol car with his physically overbearing partner Flass, symbolizing his feeling of being trapped within a hopelessly corrupt system. Wayne, on the other hand, is shown in large, open surroundings, often without even panel borders to close him in, demonstrating his ability to operate outside the law but also his lack of a clear plan for doing so.

The story of Jim Gordon being the one good cop in a sea of corruption isn’t particularly original, but it does help illustrate why Gotham City needs someone like Batman, and it’s also consistent with Miller’s apparent negative view of government and organized structures in general. This story’s real strength is the naturalistic approach to the character. Miller very intentionally avoids the more outlandish elements of the Batman mythos, instead focusing on corrupt cops and street-level crime – it’s much more Martin Scorsese than Tim Burton.

The parallel narratives of Jim Gordon and Bruce Wayne each build to a point where we see why an idea as bizarre as Batman is the only way forward. Initially concerned only with being recognized, Wayne wears a simple disguise on his first foray into crime-fighting. Unfortunately his approach lacks the intimidation factor that he needs, and things quickly spiral out of control, leading to an unwanted confrontation with the police as well as a future Batman villain in the form of Selina Kyle.

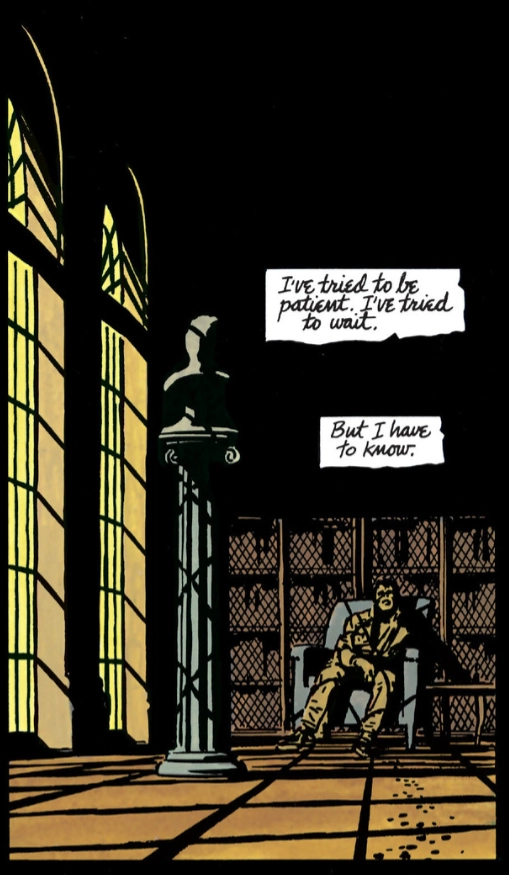

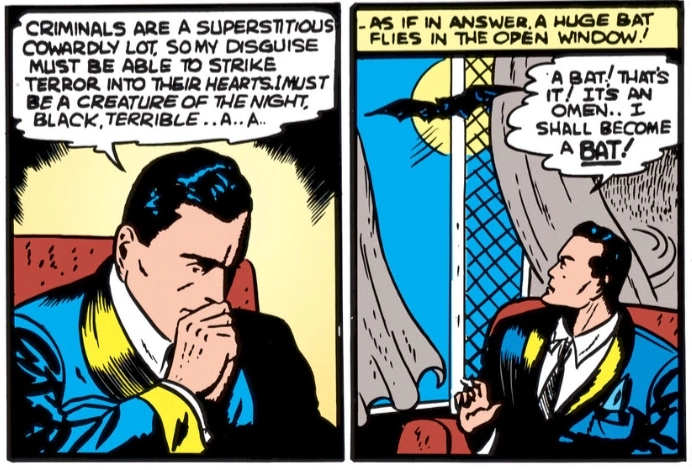

After a harrowing escape through the streets of Gotham, Wayne finds himself back home, badly injured and trying to figure out what went wrong. Miller very cleverly calls back to the original Batman origin story first published in Detective Comics #33 in 1939. In the original story, Wayne sits in a chair contemplating his coming war on crime and surmising that he’ll need a disguise, when he is surprised by a bat flying by the window. Miller expands this scene from three panels to three pages, giving Wayne a reason for thinking he needs a frightening disguise and generally infusing a great deal more drama and angst into the proceedings.

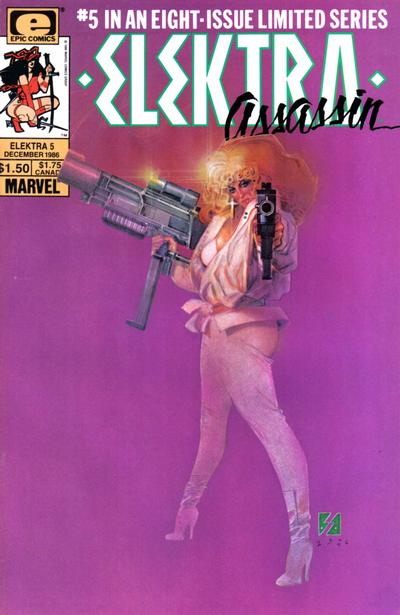

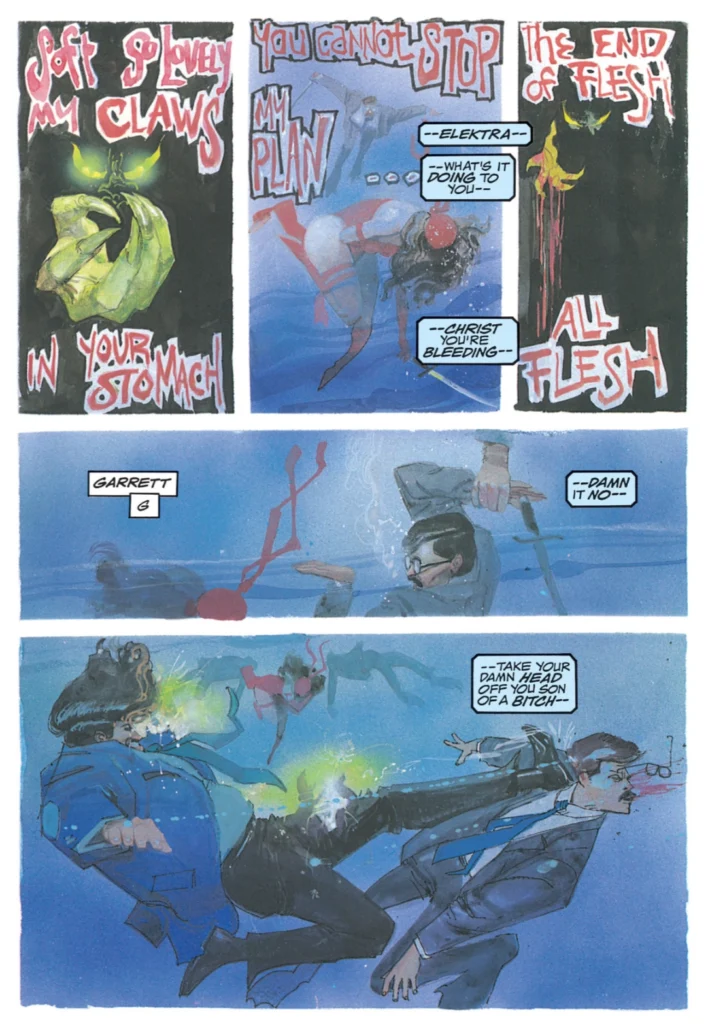

Elektra: Assassin #5 “Chastity”

Story by Frank Miller; artwork by Bill Sienkiewicz; lettering by Jim Novak

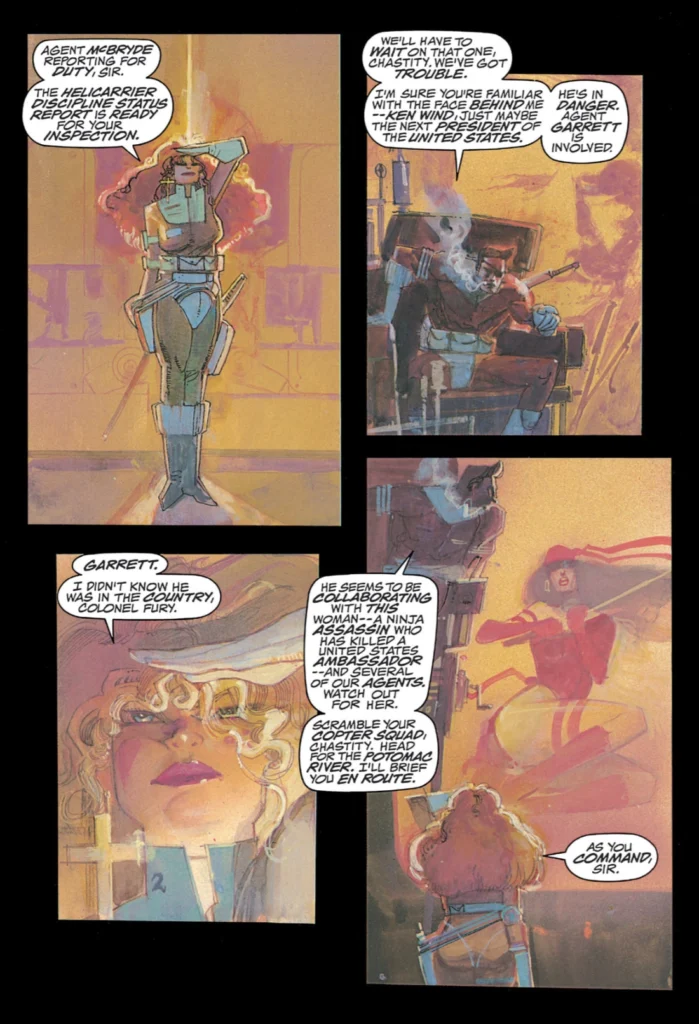

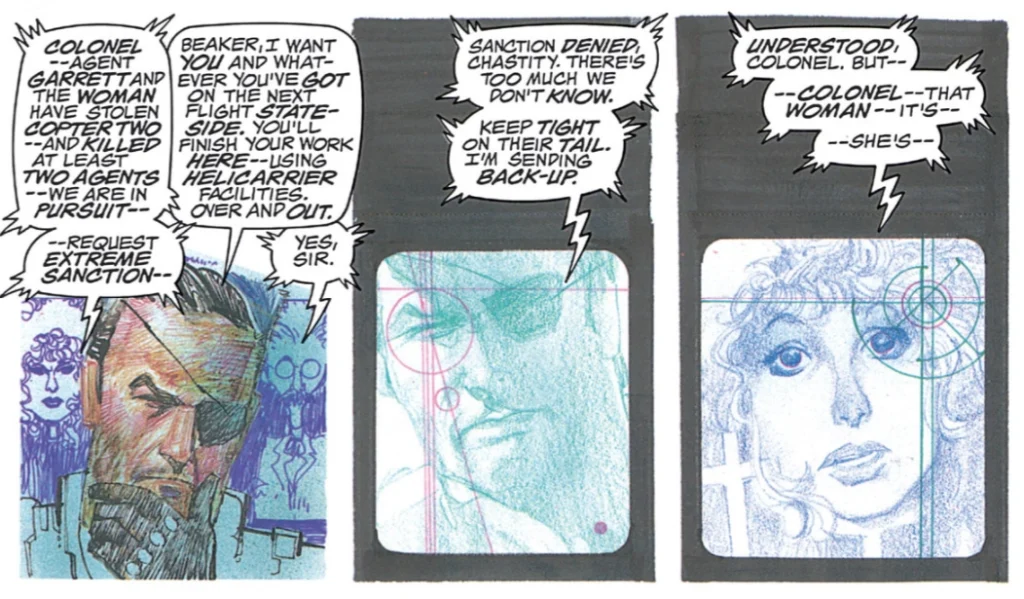

Issue 5 introduces us to SHIELD agent Chastity McBryde, a character type that Miller seems fascinated by and will come back to several times over the course of his work: that of the highly competent and skilled operative trapped in a corrupt and ineffective organization, but resigned to follow orders and do their best. Chastity is cut from the same cloth as Miller’s characterizations of Captain America in Daredevil: Born Again, and Superman in The Dark Knight Returns, and will return to with Martha Washington in Give Me Liberty, arguably the most thoughtful of his 1990s work.

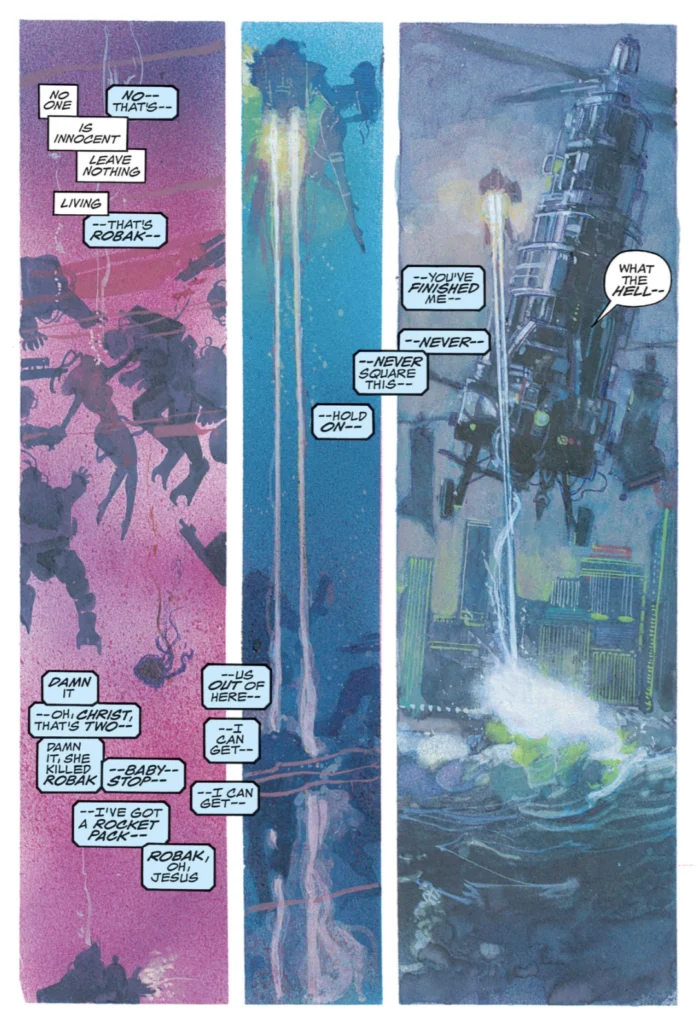

This issue keeps up the fast pace established in the previous installment. Sienkiewicz depicts most of the action with a fairly straightforward painting style, jumping into more stylized abstraction when he wants to emphasize the psychic attacks on Elektra by her adversary the Beast (or are they just hallucinations?), or Nick Fury’s cold detachment as he follows events from afar.

Miller continues to use short, disjointed caption boxes for the internal thoughts of his two protagonists. It keeps the pace moving and also gives a sense of the panic that the characters are feeling as they fend of attacks from the Beast’s evil ninjas as well as a small army of SHIELD agents under the command of Agent McBryde. Letterer Jim Novak deserves some of the credit for making these sequences work as well as they do – I can’t imagine what Miller’s script must have looked like, but Novak places the caption boxes so that they lead us through Sienkiewicz’s artwork, which we may get lost in otherwise.

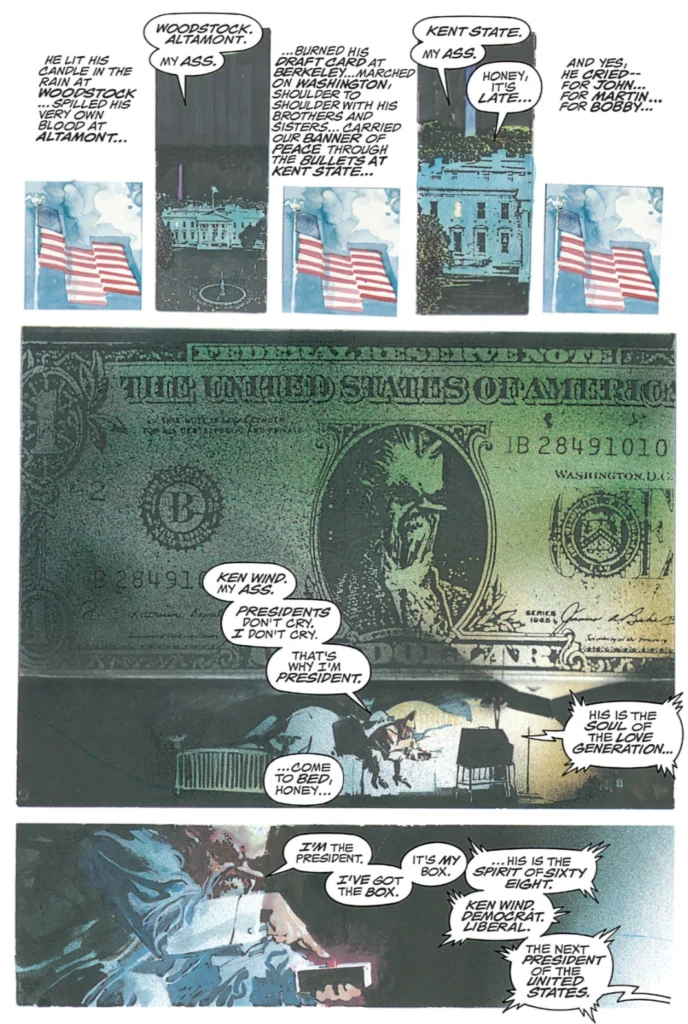

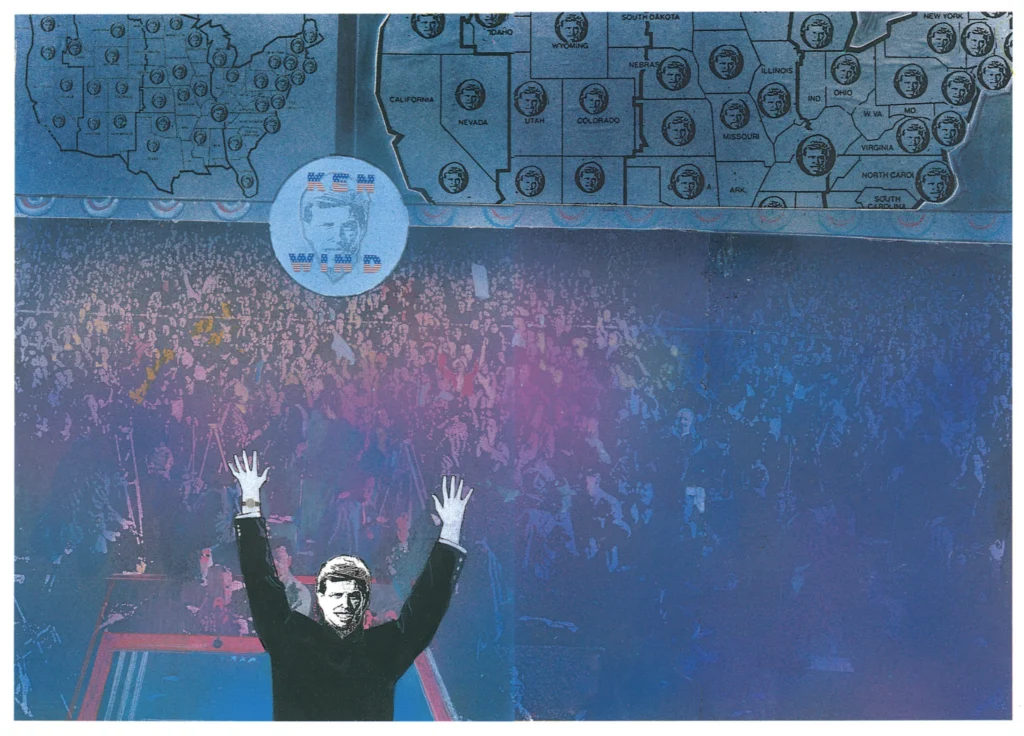

A brief and seemingly irrelevant aside has the U. S. President (a clear caricature of Ronald Reagan) watching a campaign ad for Ken Wind, his challenger in the coming election and secretly Elektra’s foe, the Beast, in disguise. Wind’s empty and hyperbolic political message, and the President’s machismo-laden reaction to it, illustrate Miller’s seeming disdain for both sides of the politial spectrum, at least as it existed in the 1980s.

Miller continues to present the main viewpoint character, John Garrett, as an utterly odious man with few if any redeeming qualities. Throughout the action he has to force himself not to focus on ogling Elektra’s body, and it is made clear that his concern over the deaths of relatively innocent SHIELD agents comes from his own sense of self-preservation. It is as though Miller wants to test the readers, to see how awful Garrett can be while still ostensibly being the hero.

November 1986

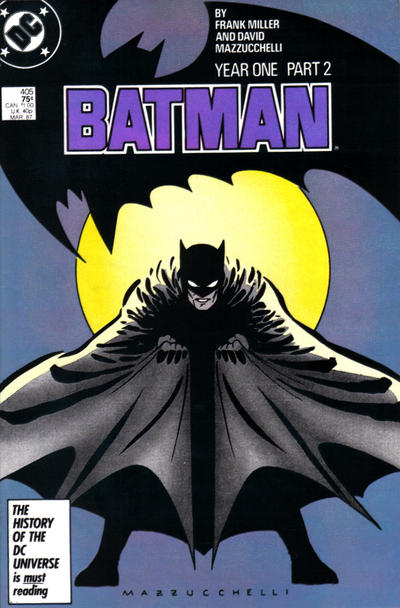

Batman #405 “Year One Chapter Two: War is Declared”

Story by Frank Miller; artwork by David Mazzucchelli; color by Richmond Lewis; lettering by Todd Klein

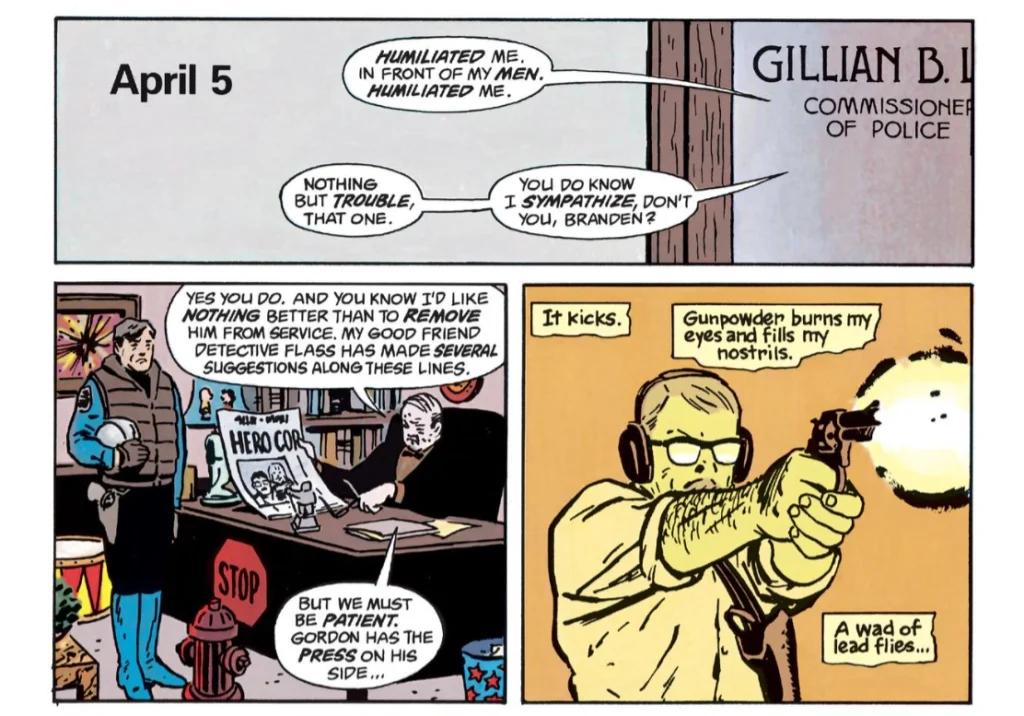

A month later, James Gordon continues to make waves at work, shining a light on a police force that is overwhelmed by incompetence and corruption. Gordon continues to fill a similar role to that of Ben Urich, the beleaguered Daily Bugle reporter in Daredevil: Born Again. Gordon’s voice is world weary and sarcastic, but unlike Urich he never gives in. Gordon is highly competent, almost supernaturally so, which gives him a position of strength from which to stand up against the establishment.

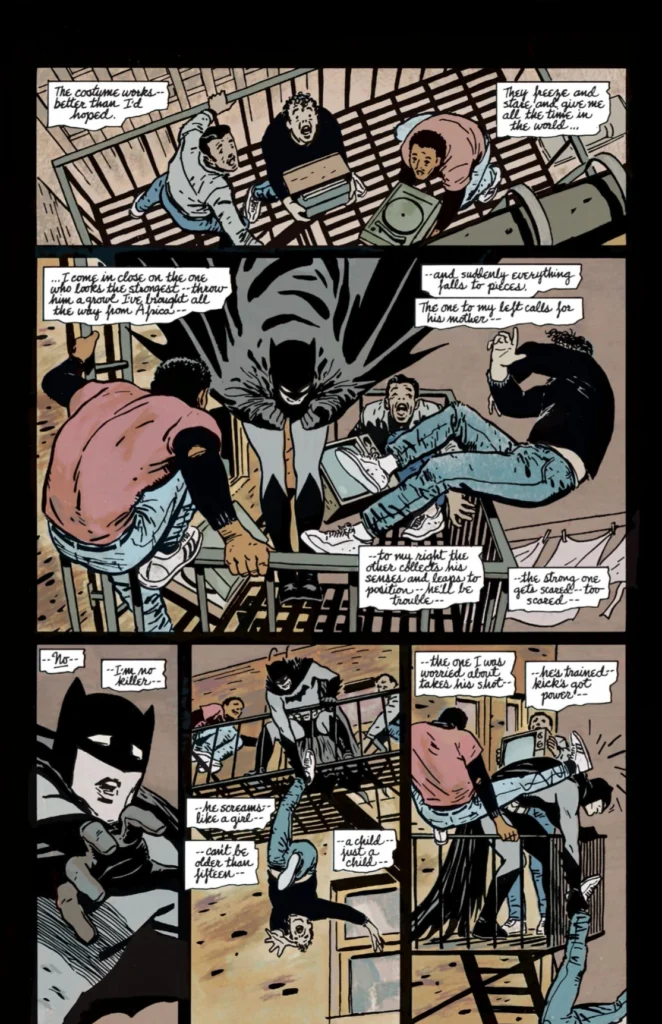

Meanwhile, the Batman makes his first appearance on the streets of Gotham. Miller wisely avoids spending any time on minutia like discovering the batcave or inventing all the weird bat-gadgets – that is clearly not an aspect of the character he’s particularly interested in.

The costume clearly gives Bruce Wayne a boost in confidence, but it’s not an instant transformation. In one of his first outings, he narrowly avoids an accidental death as he attempts to stop a burglary.

The Batman seems to become more formidable the higher up the crime ladder he goes. We see him making mistakes when addressing street crime and burglaries, but once he starts going after the “bigger fish” he gets more and more effective. As he says himself just before a dramatic stunt intended to intimidate Gotham’s ruling elite, “The costume – and the weapons – have been tested. It’s time to get serious.”

Along the way, Miller introduces several story elements that will attach themselves to the character of Batman and become as essential to the overall mythos as the Joker or the Penguin. Mob Boss Carmine “The Roman” Falcone, who will become a regular character in the Batman comics and feature as a major character in several Batman films. Miller also spends a lot of this issue on the idea that the police would treat a vigilante like the Batman as a criminal, not an ally – there are several scenes depicting attempts to trap and capture the Batman that will likewise find their way into future films and television productions.

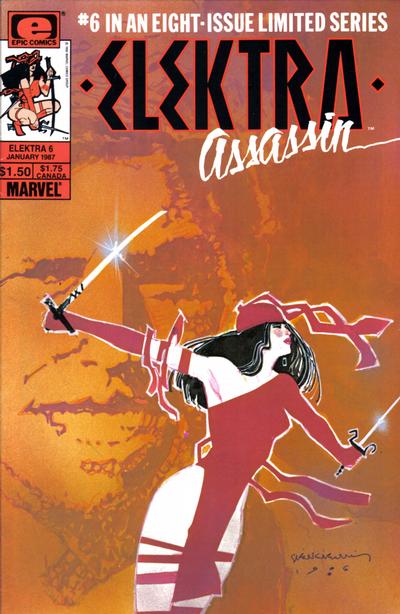

Elektra: Assassin #6 “What We’re Fighting For”

Story by Frank Miller; artwork by Bill Sienkiewicz; lettering by Jim Novak

After the relentless pace of the previous two issues, our two main characters take a back seat as Miller and Sienkiewicz spend this issue ensuring that the readers understand the plot. As it was originally coming out (and indeed, ever since), much commentary and criticism was directed at the hallucinatory quality of the series, whether or not its creation was drug-induced, and if you needed drugs to understand it. But honestly, the plot of Elektra: Assassin is pretty simple.

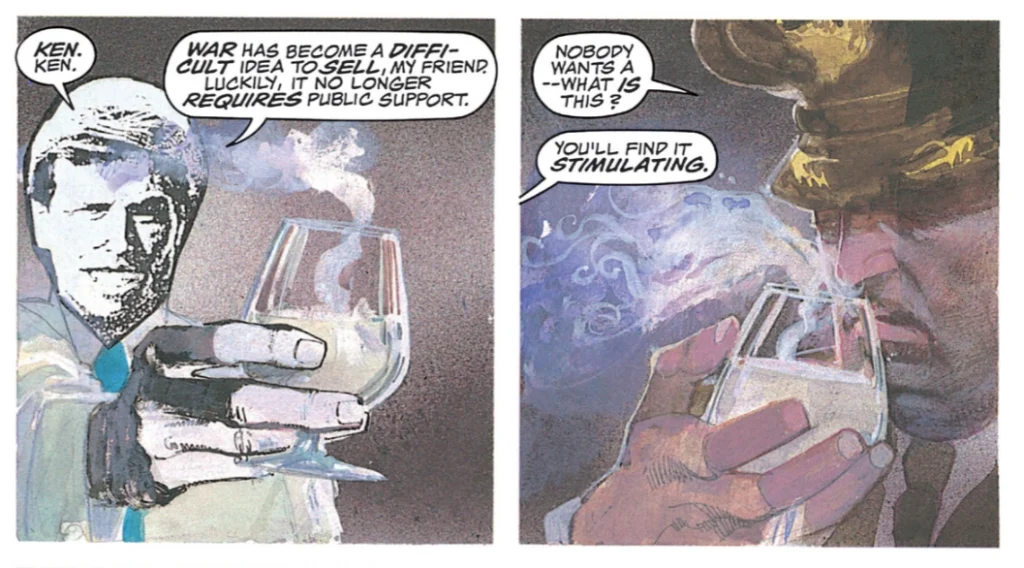

While Elektra and Garrett hole up in a sleazy motel, Presidential hopeful (and psychic demon in disguise) Ken Wind meets with an unnamed army general, presenting a persona very different to the head-in-the-clouds liberal his campaign ads make him out to be.

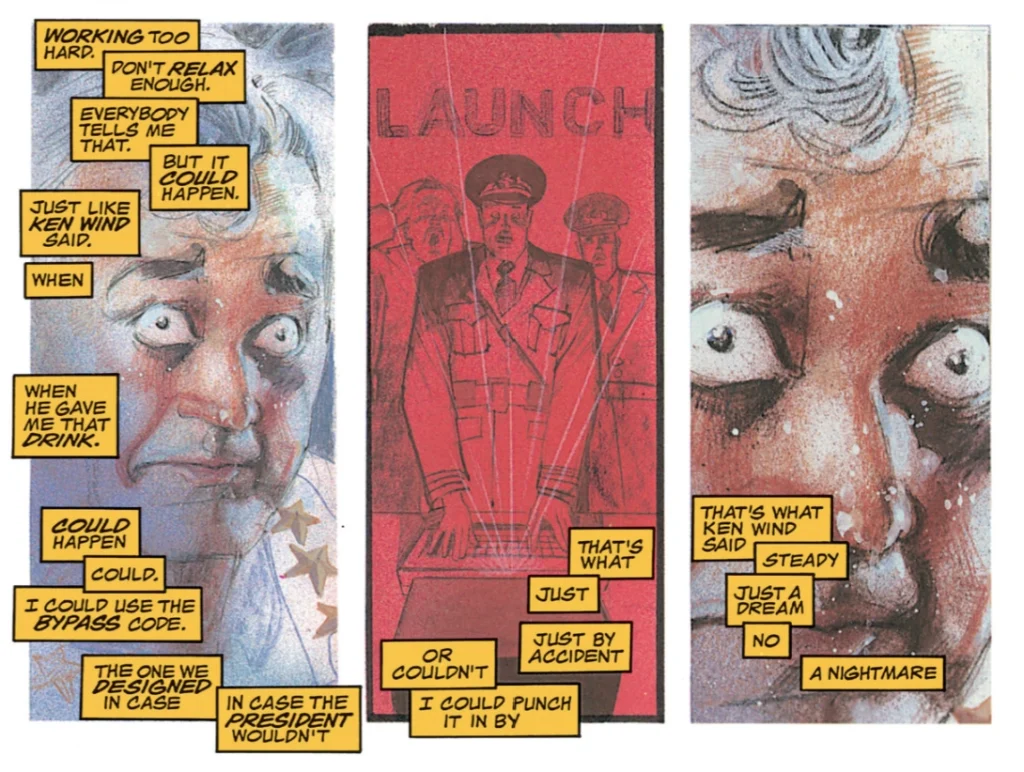

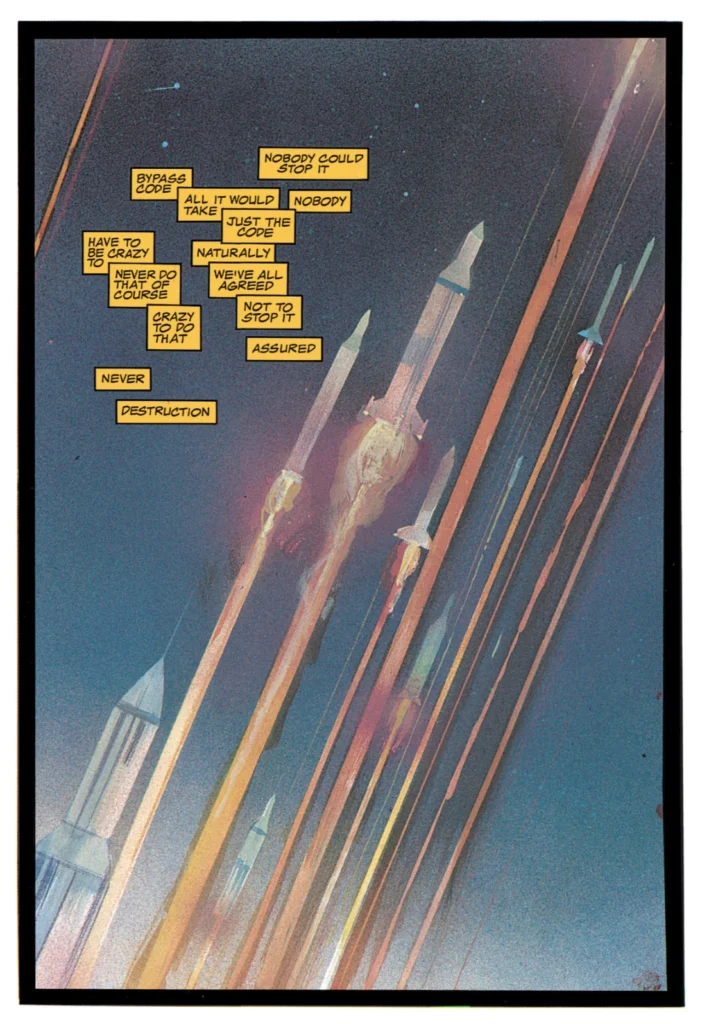

Wind psychically dominates the general, filling his head with disjointed thoughts about using his access to instigate a nuclear strike against Russia. It more clearly explains just what Elektra wants to prevent by foiling the Beast’s plans, although it is fairly low hanging dramatic fruit – nuclear armageddon was the primary source of most existential anxiety in the 1980s, after all.

Elektra: Assassin #6 pages 16 and 17. © Marvel.

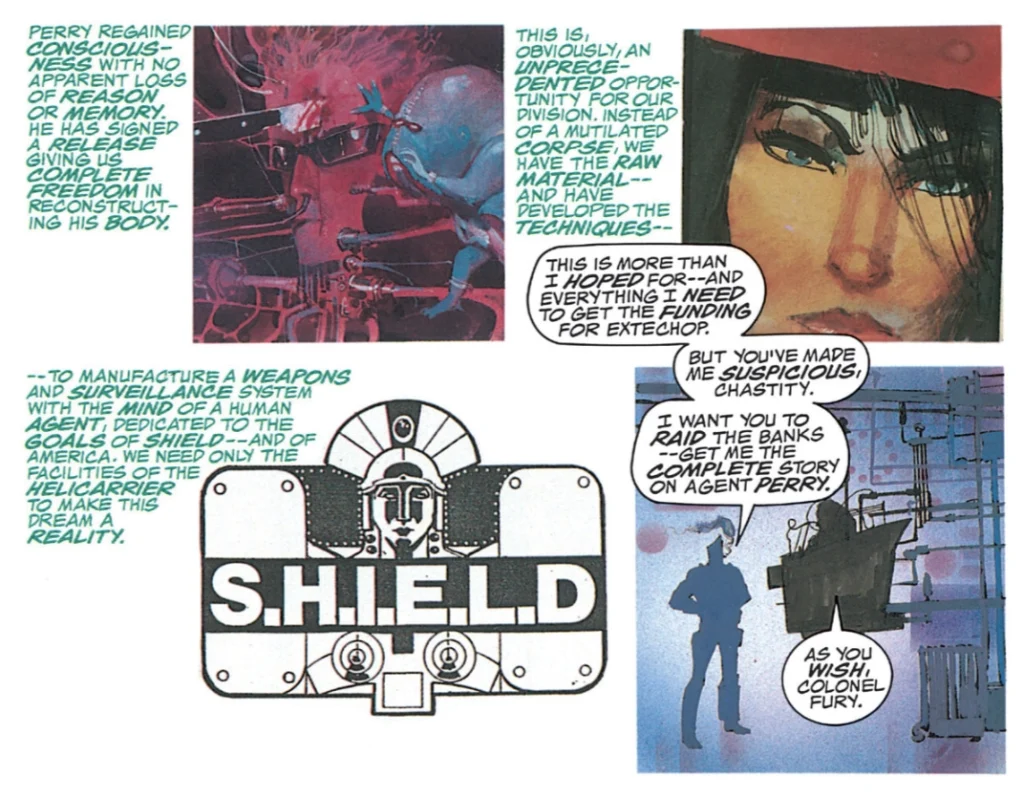

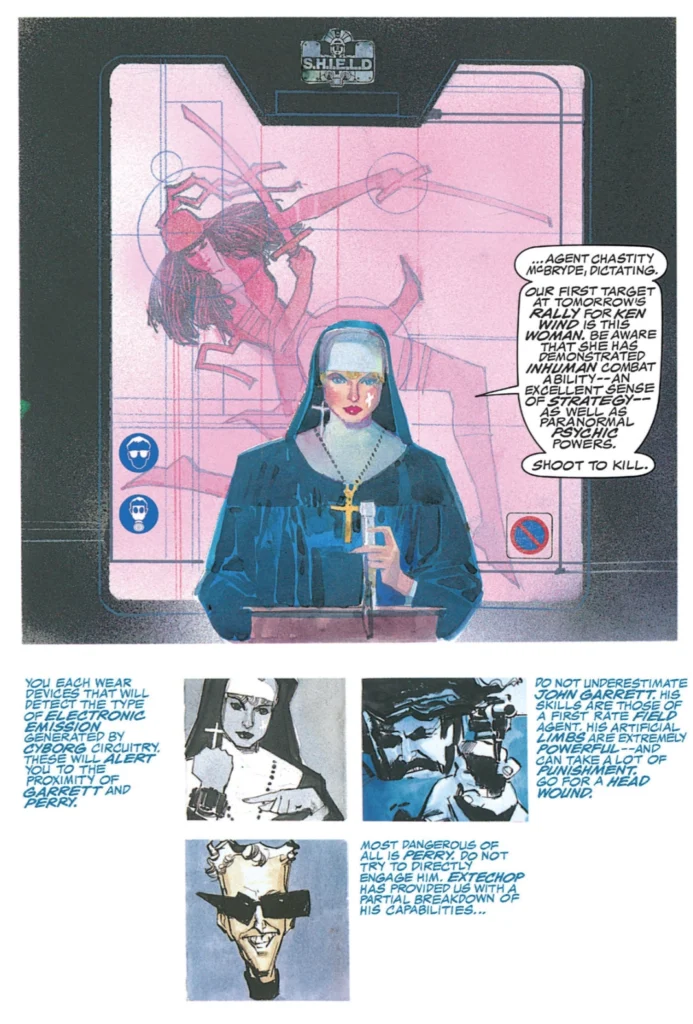

Meanwhile, we get a massive info-dump in the form of Agent McBryde’s report to Nick Fury on the events of the previous issue, followed by a progress report from ExTechOp, SHIELD’s bioweapons division. Between the two reports it becomes clear that ExTechOp has been recruiting convicted criminals and turning them into superhuman cyborgs. In spite of the disturbing implications, Fury sees the project as promising, and a way for him to get more funding.

ExTechOp’s newest subject is Garrett’s former partner Arthur Perry, killed by Elektra in issue 3. What Fury doesn’t know is that Perry is a convicted multiple rapist and murderer who killed his own family as a child. Fury shuts down the project as soon as he finds out, but not soon enough to prevent Perry from escaping SHIELD custody with the assistance of a vat-grown lab assistant he calls Chuck.

This unfortunately sets up another dramatic cliché, one common to superhero stories: having established Garrett as at least somewhat superhuman thanks to his cybernetic body, Miller now gives him an adversary in Perry, who is essentially the same character only more evil and more powerful.

In any case, the plot should now be clear to any readers who have been paying attention. Elektra is hell-bent on stopping the Beast, a supernatural being who is poised to become the next President of the United States, and will use that power to launch a nuclear strike that will destroy the world. She is unwilling or unable to get help from the authorities (in this case, Nick Fury and SHIELD), who view her as a presidential assassin who must be stopped. Meanwhile, SHIELD’s own bioweapons division have provided a secondary arch-enemy for Elektra’s only ally.

When you lay it all out it’s not difficult to follow at all, although it is a little silly and cliché-ridden. Where Elektra: Assassin succeeds is in the telling, not the tale itself – they have successfully managed to present a story from the point of view of a character whose grip on reality is tenuous at best, and they’ve given us an idea of what it must be like to be that character. That’s the brilliance.

December 1986

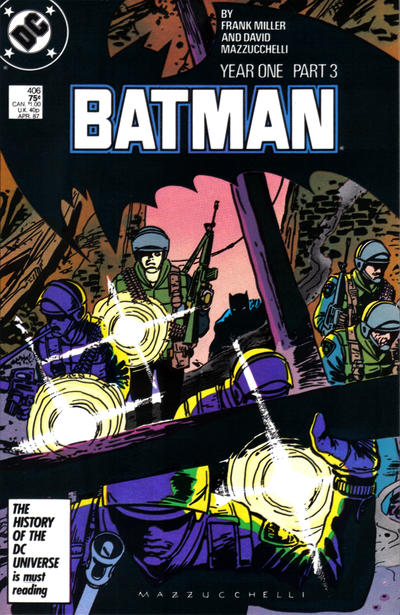

Batman #406 “Year One Chapter Three: Black Dawn”

Story by Frank Miller; artwork by David Mazzucchelli; color by Richmond Lewis; lettering by Todd Klein

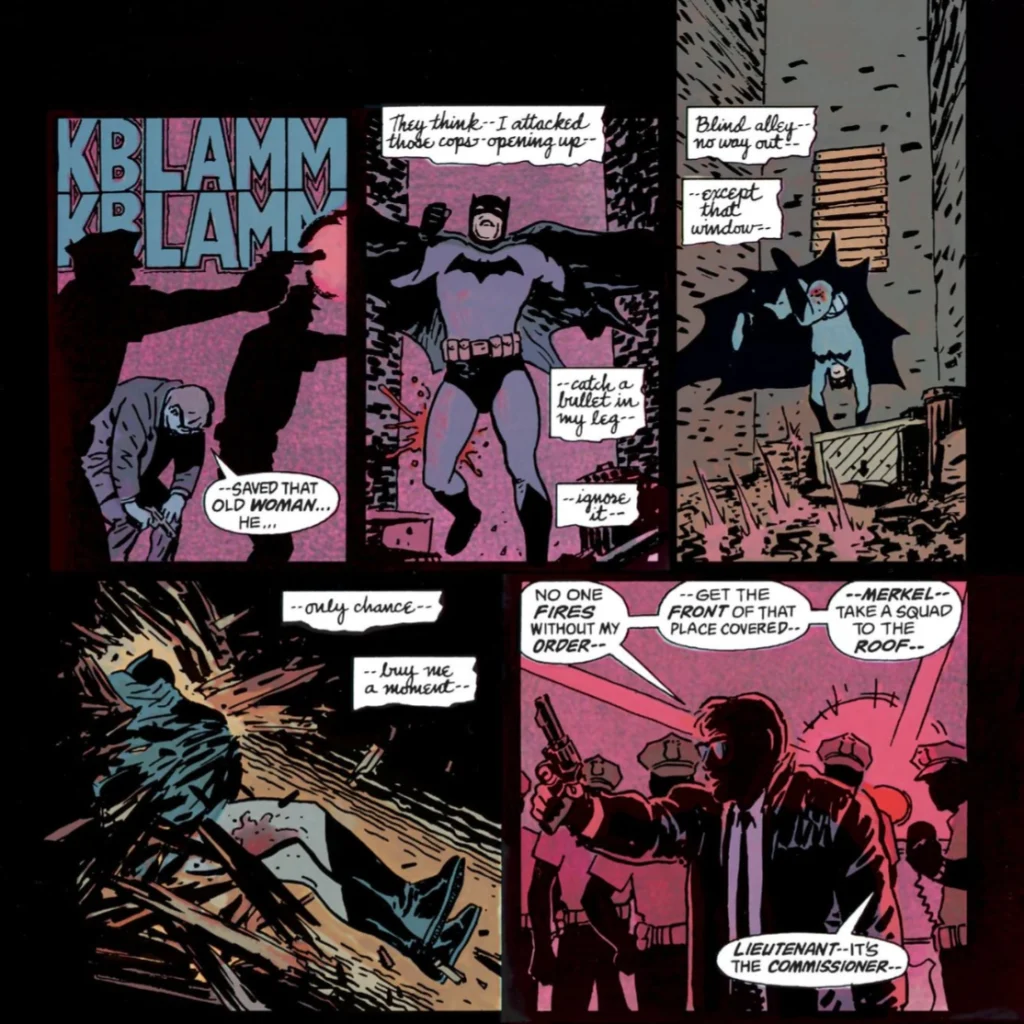

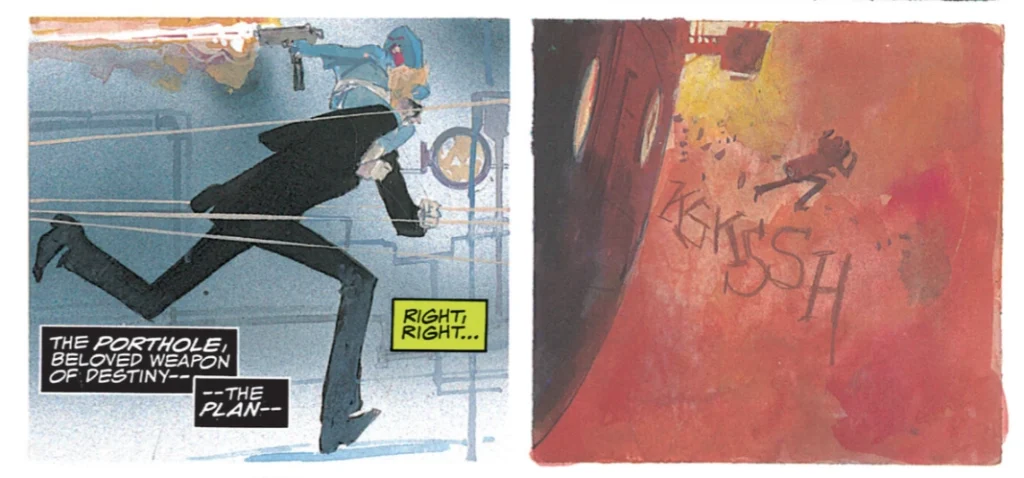

Over half of this issue is given over to a single action set piece. It almost reads more like a police procedural than a superhero comic book, with a level of gritty naturalism that will be a massive influence on filmmakers like Christopher Nolan and Matt Reeves. David Mazzucchelli rises to the task admirably, rendering the scenes with flawless draftsmanship that strikes a perfect balance between realistic detail and fluid action.

Over Gordon’s protests, a Gotham police tactical team (whose leader Gordon clashed with in the previous issue) pursues the Batman into a derelict building that’s just been partially demolished on the order of the police commissioner. There is an extended pursuit through the building, during which the Batman runs rings around the police despite having an injured leg. The character is now possessed of supreme confidence in his abilities and methods – his days of beating himself up over his mistakes are at an end.

To further illustrate that point, the Batman uses a device of his own invention to summon a swarm of bats to cover his escape. It is difficult to imagine this scene working without Mazzucchelli’s superb rendering. His stark, high contrast drawings bring a cinematic quality to something that could easily look indistinct or ridiculous in the hands of a lesser artist.

Batman #406 pages 14 and 15. © DC Comics.

The remainder of the issue is given over to two sub-plots, one of which serves to keep the story grounded, while the other opens the door to one of the more outlandish elements of the Batman mythos.

James Gordon’s “only good cop in a corrupt town” risks becoming a character a little too virtuous for the grim and gritty world Miller wants to tell his story in. Gordon has an extremely high pressure job and a pregnant wife at home, which makes him perfectly placed for an ill-advised workplace romance. This puts him in a compromising position that his corrupt boss will try to take advantage of in the next issue, giving Gordon another opportunity to demonstrate just how incorruptible he is.

Meanwhile, having witnessed the Batman’s dramatic escape from the police earlier in the issue, Selina Kyle is inspired to change careers, changing her dominatrix outfit for a cat costume…

Elektra: Assassin #7 “Vox Populi”

Story by Frank Miller; artwork by Bill Sienkiewicz; lettering by Jim Novak

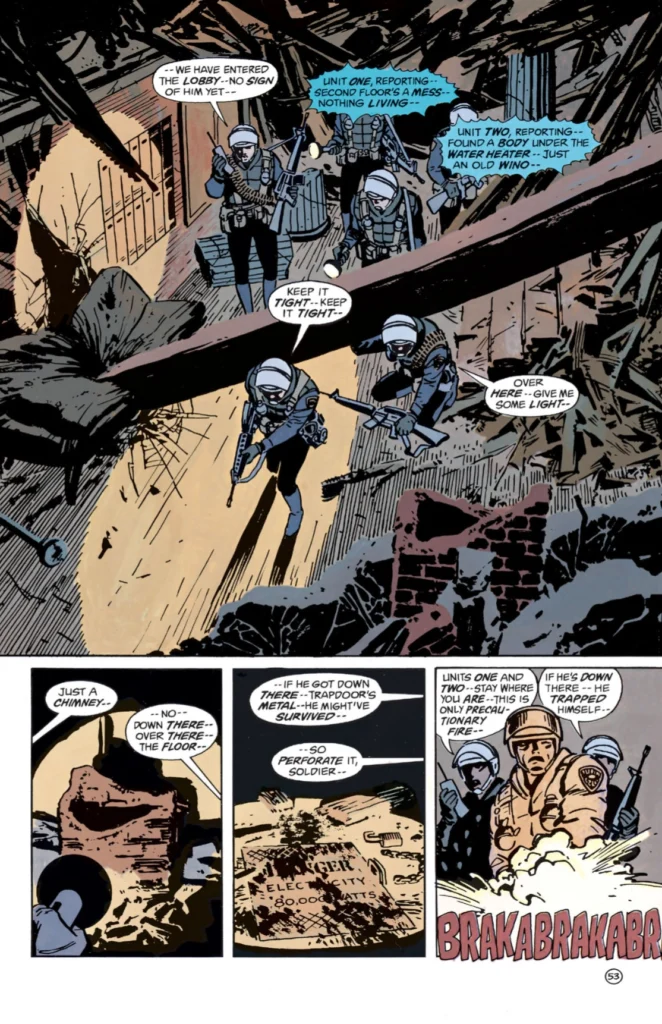

SHIELD certainly has its hands full as this issue opens: they have failed to recapture a homicidal psychopath who has been given a superhuman artificial body by their own bio-weapons division. On top of that, they are expecting Elektra, the world’s greatest assassin, to make an attempt on presidential hopeful Ken Wind’s life during a rally that will be attended by thousands, making security challenging to say the least.

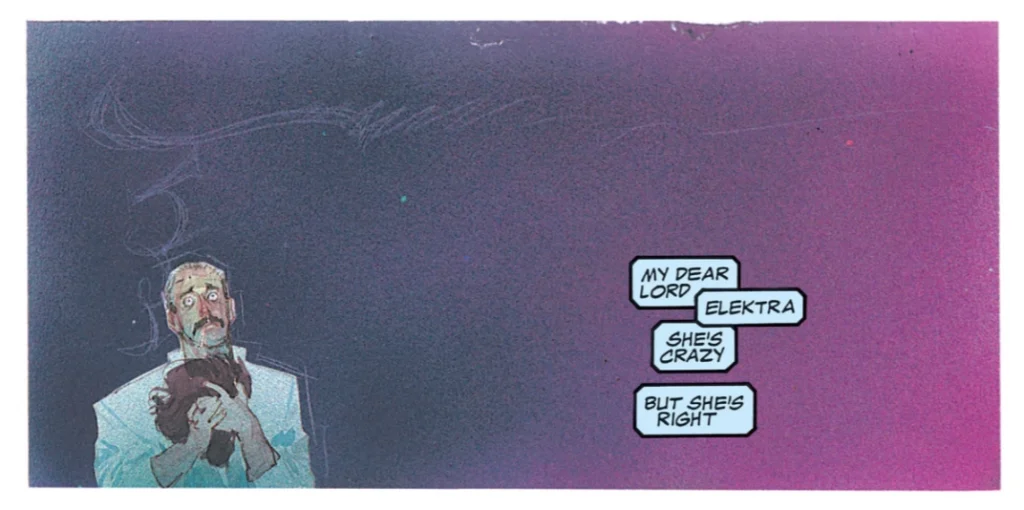

After last issue’s recap and exposition, this issue puts all the pieces on the chessboard for Elektra’s final confrontation with Ken Wind, AKA the Beast. Elektra’s motives are made absolutely clear, as is SHIELD’s cluelessness. More importantly, Garrett finally makes the jump from willing but disgruntled lackey to true believer, as Elektra finally makes him fully aware of what their adversary is planning.

There’s not a lot of story in this issue, but Sienkiewicz does his best work on the series so far, making great use of wide panels, double-page spreads, and a variety of painting styles. He uses more vivid colors, perhaps to give the sense of a heightened reality as the story moves into its final act.

So then what happened?

Both Elektra: Assassin and Batman: Year One concluded in January 1987. In an interview in Amazing Heroes #69 (April 1985), Miller indicated that he was working on writing and drawing an Elektra graphic novel at the same time he was preparing The Dark Knight Returns. Judging from preview artwork included with the article, this was Elektra Lives Again, which wouldn’t see publication until 1990.

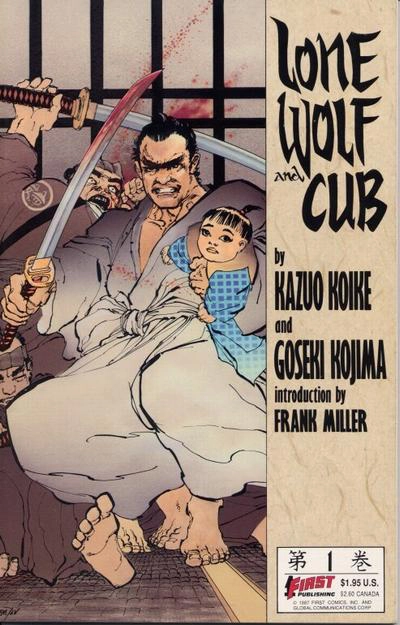

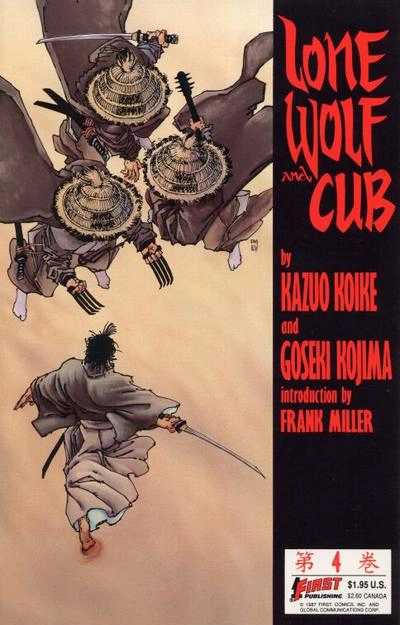

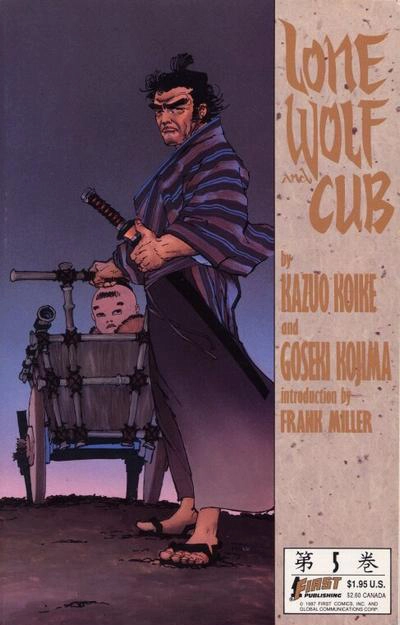

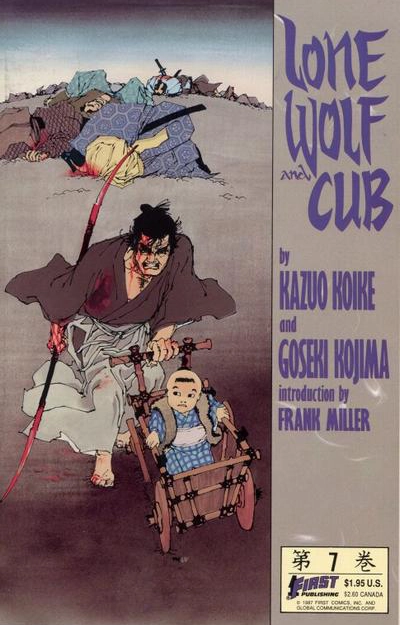

The only major work Miller did between 1987 and 1990 was cover artwork and text introductions for the first 12 issues of the English language reprints of Lone Wolf and Cub, published by First Comics between 1987 and 1991. Even here, Miller’s incredible influence in the world of comics could be felt – while it goes without saying that Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s masterpiece stands entirely on its own merits, having Frank Miller’s name on the covers certainly couldn’t have hurt the series’ profile in the crowded comics marketplace of 1987. Indeed, Miller’s covers have been used for American printings of Lone Wolf and Cub ever since.

Lone Wolf and Cub cover art by Frank Miller. © Frank Miller Inc.

Miller appears to have spent at least some of this time trying to break into the film business. According to contemporary interviews in Rolling Stone and Spin, Miller had moved from New York to L.A. in 1986, so a brush with Hollywood seems inevitable for the author of one of the most talked about books (graphic novel or otherwise) of the year. He is credited as a writer on the films RoboCop 2 and RoboCop 3, but the common wisdom is that very little of his vision for the character made it through to the final films. Miller would collaborate with comics industry giant Walter Simonson on the better-than-it-has-any-right-to-be Robocop vs. the Terminator in 1992, and many of his original ideas for the character would later be used in a RoboCop comic book series published by Avatar in 2003.

After a three year gap, Frank Miller came back to comics with a vengeance in 1990, creating Hard Boiled with artist Geoff Darrow, and Give Me Liberty with Watchmen co-creator Dave Gibbons. The first chapter of Sin City premiered in 1991 — it was a project that would dominate Miller’s career for the rest of the 1990s and beyond. It also gave him another shot at Hollywood fame, leading to him co-directing two Sin City movies with Desperado and Spy Kids director Robert Rodriguez, as well as acting as sole writer and director of a film adaptation of Will Eisner’s The Spirit.