Published from 1980 to 1986, Epic Illustrated stands as a symbol of two critical developments in Marvel’s evolving publishing strategy that had a profound effect on the entire comics industry. Its nature as an anthology contributed to the rise of comics creators owning and controlling the rights to their work. But its cancellation was one of the first steps towards the end of the newsstand as the primary venue where comics were bought and sold.

What started as an imitation forced Marvel to move forward

Heavy Metal, an American anthology magazine consisting primarily of fantasy and science fiction comics stories translated from European material, was a reasonable success when it started in 1978. Marvel took notice and quickly began working on its own similarly themed title. Produced for the magazine market and ostensibly for adult readers, both publications were able to get around the restrictive Comics Code (that aimed to protect comics’ supposed primary readership of children) in order to feature more sophisticated material. But while Heavy Metal was drawing from a fairly large library of European reprints, Marvel would need to commission new work. In order to get the high quality they were after, they would have to let the writers and artists retain ownership of their work.

Up until this point, creators worked for Marvel on a strictly “work for hire” basis, meaning that any work they produced would be owned by Marvel. They couldn’t expect to benefit from reprints, merchandising, or adaptations of their work – even the idea of earning royalties based on how well their work sold was a few years away. Throughout the history of comics up to this point this was a normal arrangement and the only game in town. However, things were starting to change as smaller publishers started appearing who were happy to let creators keep the rights to the work they created. In order to attract the high caliber of talent they needed, the editors of Epic Illustrated would need to offer creator ownership. This would allow Marvel to dip its corporate toe in to see if they could get used to the idea.

Creator ownership led to more innovative work

And get used to it they did, as within a few years Epic expanded from a single magazine to an entire line of comics published by Marvel. The Epic line featured creator owned material that was often edgier than Marvel’s core stable of superhero comics, balanced by the occasional title such as Elektra: Assassin that featured Marvel-owned characters in experimental, adult-oriented stories. Epic’s success demonstrated that there was an audience out there hungry for comics that were more sophisticated, and that Marvel could profit from publishing them even if the creators retained their rights to their work.

The Epic books were all published solely for the direct market, the network of comic book stores that had started to appear in the late 1970s. Before the direct market, comics were sold primarily at newsstands and unsold copies were returnable, which meant that they had to sell a lot of copies in order to be profitable. But comic book stores bought their comics on a non-returnable basis, so a book in the direct market had a wider profit margin and could be successful with a much smaller audience. Marvel had tried selling comics exclusively to this market before with some success. The Epic line was the start of them focusing more and more of their attention here, and less and less of it on the newsstands. By the end of the 1980s the vast majority of comic books were sold in the direct market, and newsstands were a distant memory.

The end of the newsstand

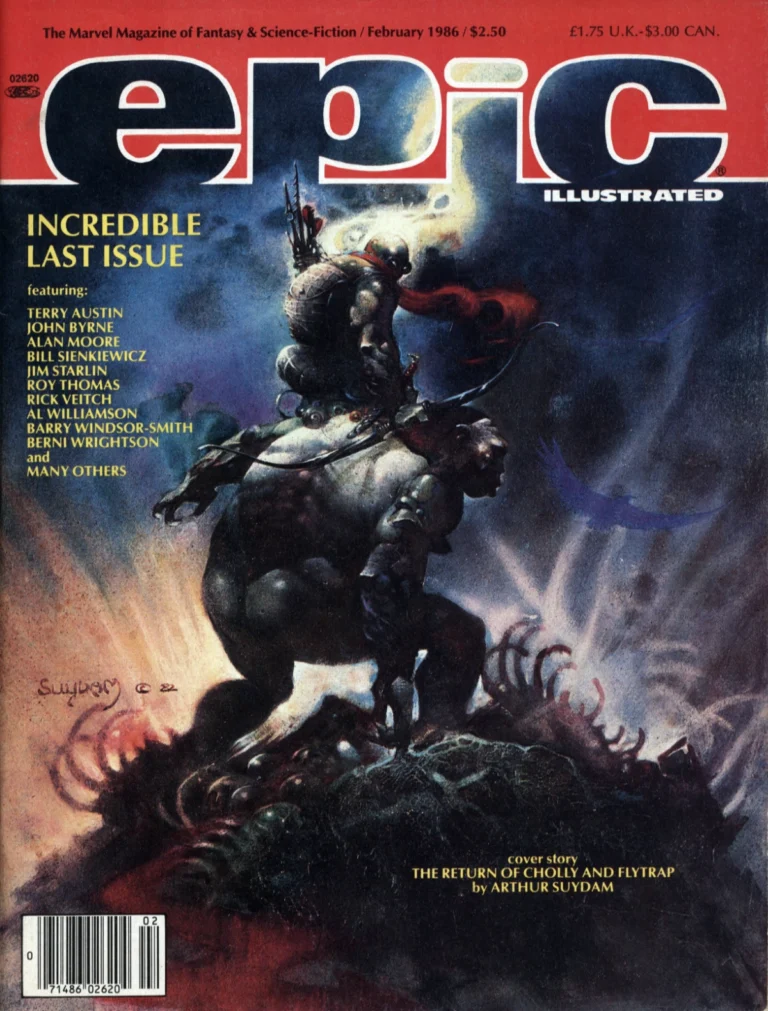

So where did that leave Epic Illustrated? Ironically it was doomed by the very line of comic book titles it spawned, and the direct market that they helped enable. By 1986 comics were already fading from newsstand shelves – even Heavy Metal, once a titan of the magazine racks, had reduced its publication to four issues per year. Citing expensive production costs that were unsustainable in a shrinking newsstand market, Epic Illustrated closed up shop, publishing its final issue in February 1986.

Original stories

That final issue sports an impressive list of talent but is a bit of a mixed bag in terms of quality – something that can be said for the magazine’s entire run, really. Most issues of Epic started out with an Overview column that gave a little background on the stories and creators, but the final issue uses most of that space for a “special thanks” to some of the behind-the-scenes production personnel. It’s great that those people get recognized, but it means that most of the stories are presented in something of a vacuum.

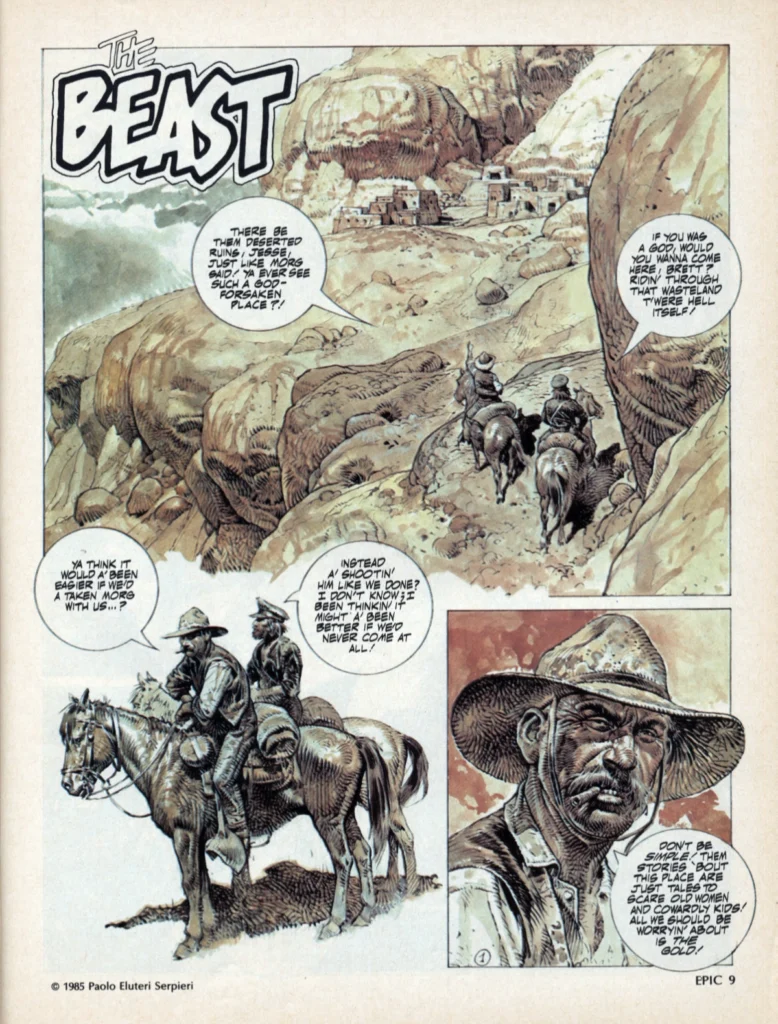

First up is “The Beast,” by Paolo Serpieri, an artist whose work frequently appeared in Heavy Metal. It’s an odd choice considering that, while Epic was clearly established as a competitor, they also made an effort to distance themselves from Heavy Metal. They rarely published work by the same artists or even in the same style. It’s a nicely illustrated piece but a bit basic, with a somewhat weak “snap” ending.

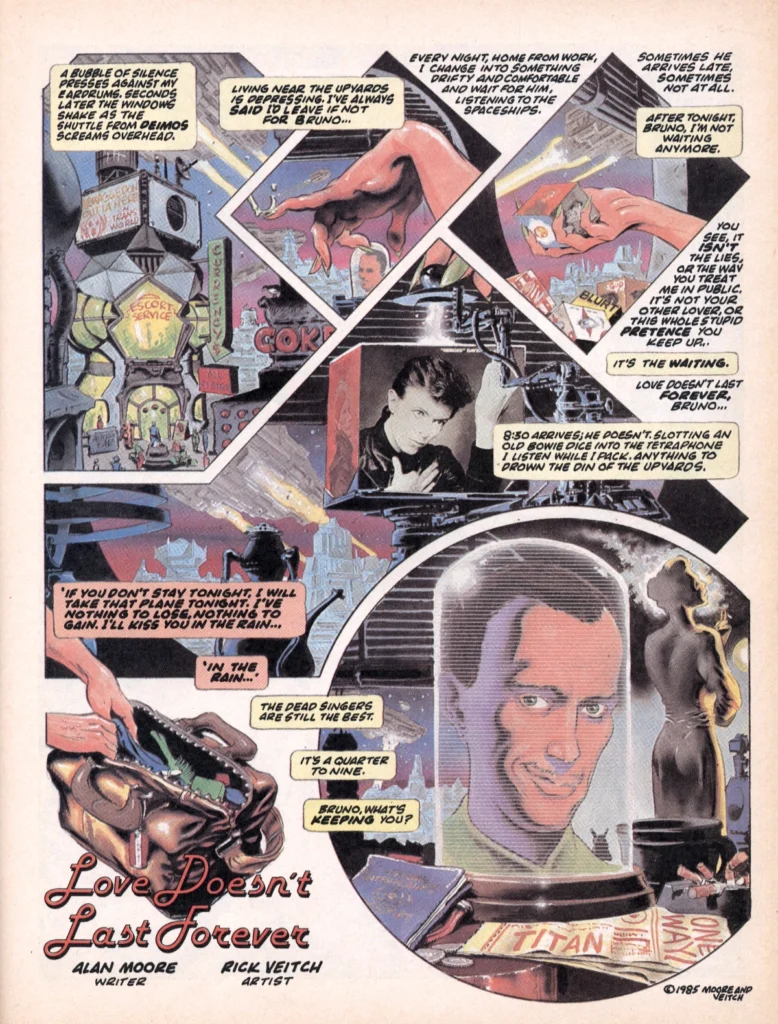

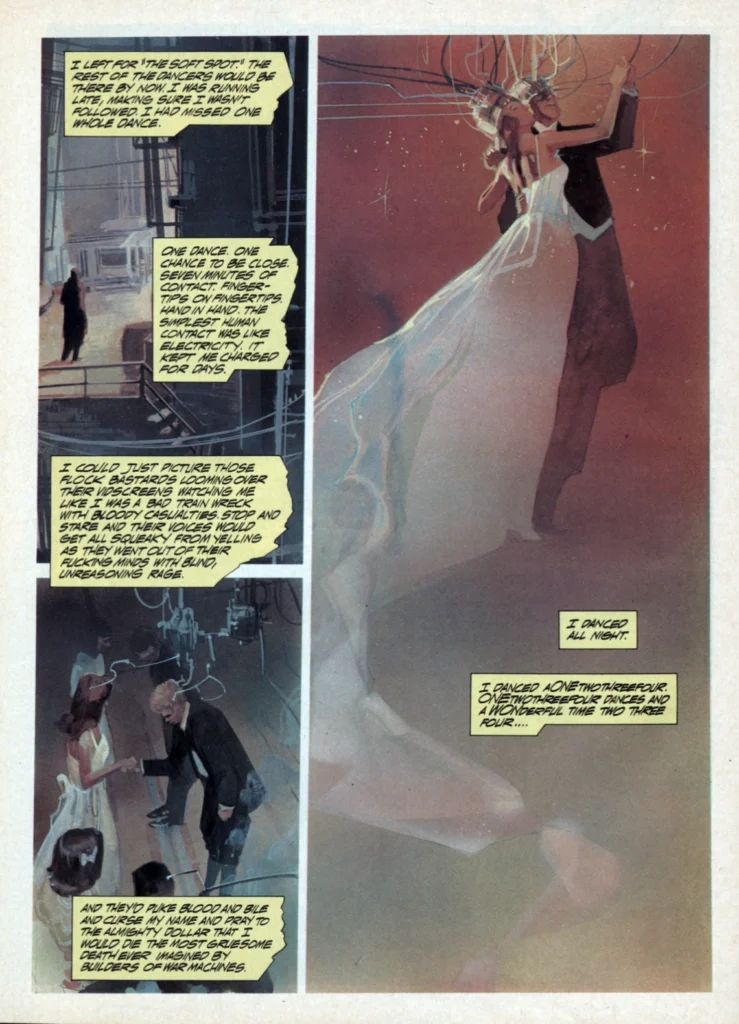

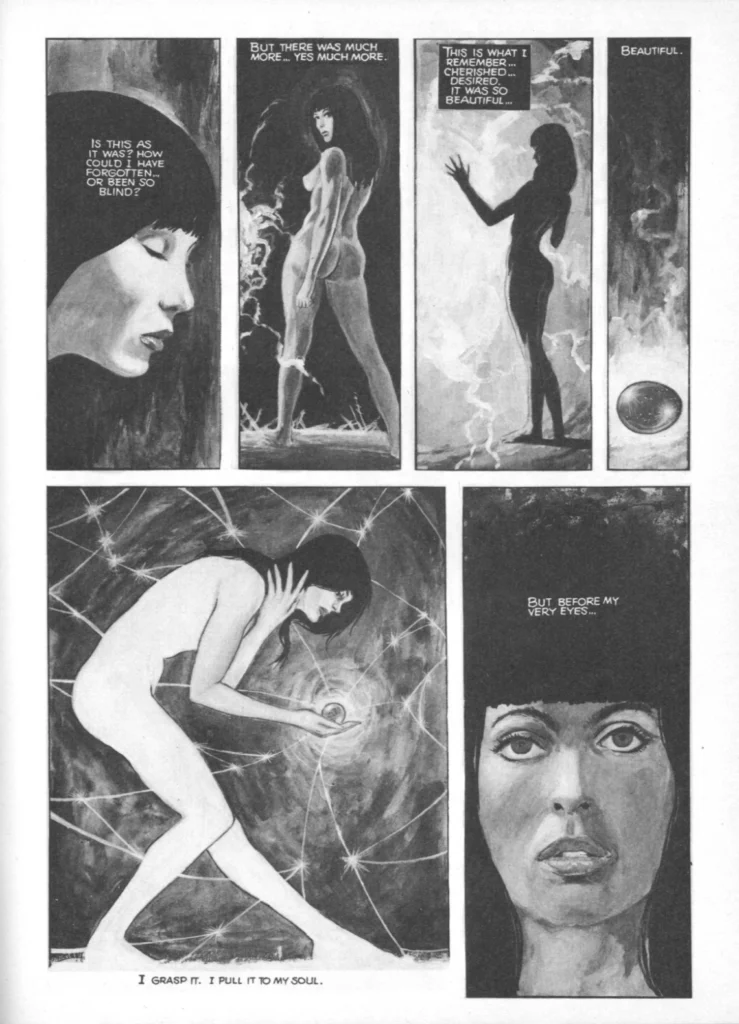

“Love Doesn’t Last Forever” is a very rare case of Alan Moore doing work for Marvel. His collaborator Rick Veitch was a frequent contributor to Epic Illustrated, so it’s easy to imagine that it was Veitch that got the story into Epic’s pages. It’s a thinly veiled AIDS allegory, a topic that was on everyone’s mind in the 1980s, and Moore treats the subject with his usual deftness. Bill Sienkiewicz gives his own take on the subject in his “Slow Dancer,” a fully painted story that’s a bit more subtle than Moore and Veitch’s piece.

Editorial constructs

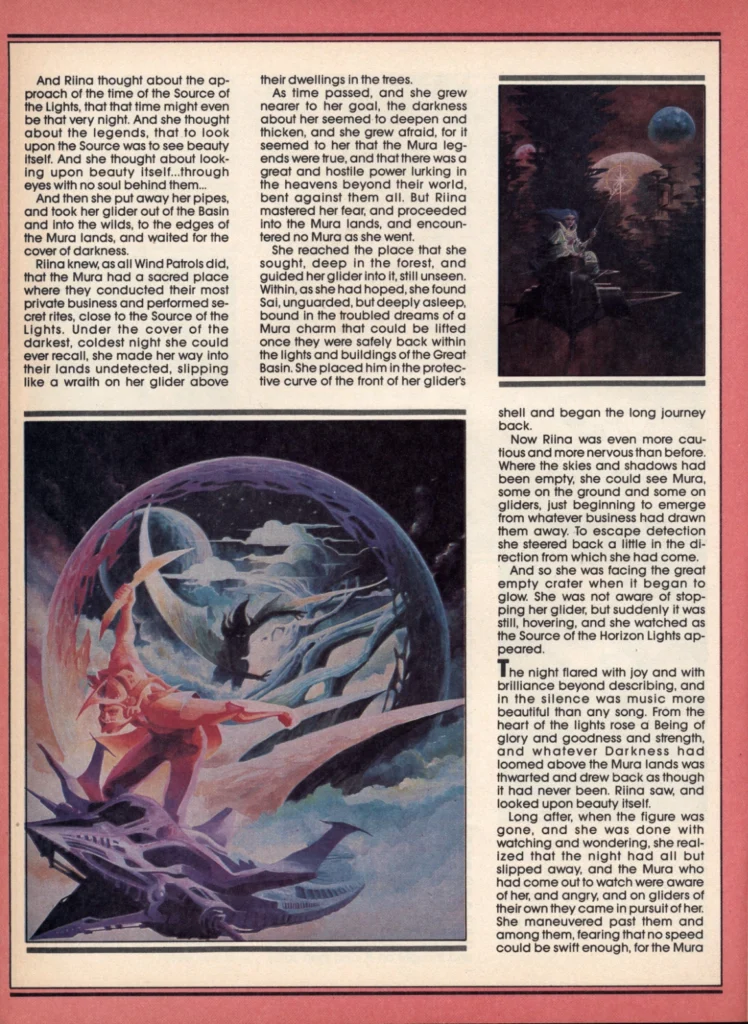

Epic often featured portfolios of single-page illustrations by both up-and-coming and established artists, and this final issue features a collection of “work-in-progress” illustrations by noted comic book artist Barry Windsor-Smith. Also featured are some very nice pieces by T. Sagrada which are unfortunately paired with a dull prose story by one of Epic’s editors, Jo Duffy. The editors of Epic would sometimes connect artists with writers in order to stick to their editorial remit of featuring illustrated stories. These editorial pairings were rarely successful, as it usually entailed a writer (or one of Epic’s staff) trying to come up with some words to go with pictures that had already been made. In this case, Duffy’s overlong wall of text forces many of the illustrations to be printed so small as to be barely visible, which surely defeats the whole purpose.

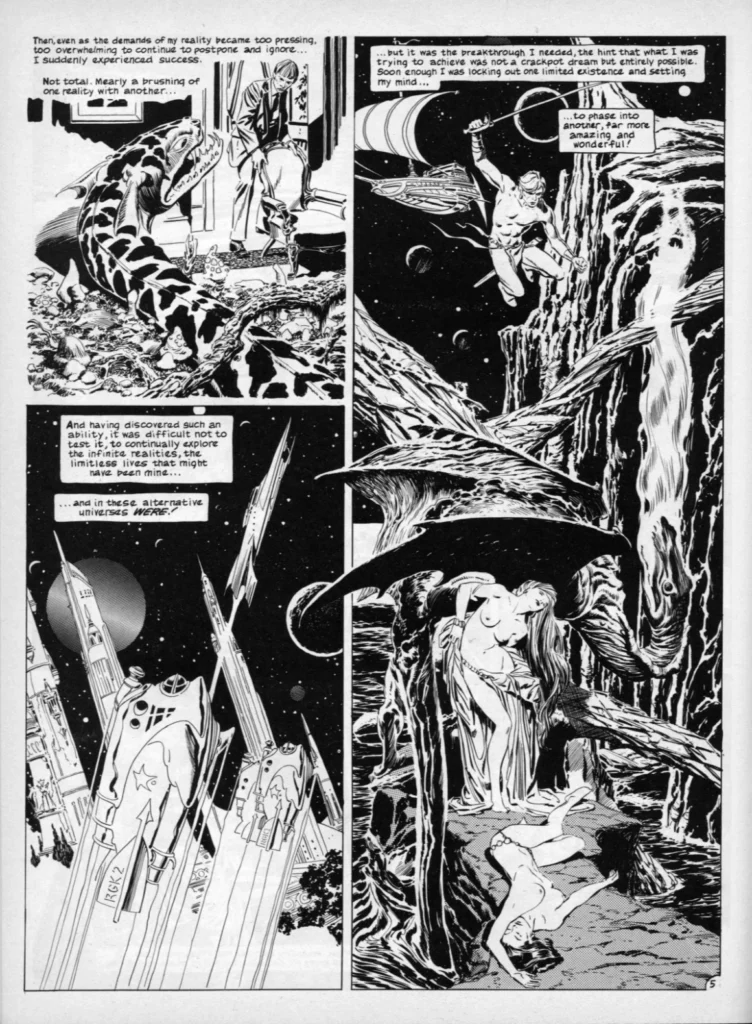

“Out of Phase” is also written by one of Epic’s editors, this time Archie Goodwin. The story seems designed specifically to showcase the talents of artist Al Williamson. In this case it’s a traditional comics story rather than prose text, and Goodwin seems to know to get out of the way and just let Williamson draw. Williamson’s particular brand of well-rendered 1930s-style adventure is front and center.

The magazine’s regular text features, Mediaview, Bookview, and Futureview, were always fairly self-indulgent pieces in which the authors talked more about themselves than about whatever film, book, or bit of culture they were reviewing, but never more so than in their final farewells. I’ve always suspected that these text pieces were needed in order for Epic to retain its status as a magazine, and thus be free from the restrictions on content that would apply to a comic book.

The final chapter of a story that would go unfinished

The artwork in the penultimate chapter of John Byrne’s “The Last Galactus Story” is technically flawless as always. Unfortunately, the story (which unfolded over the previous eight issues) plods along at a very slow pace and just isn’t that interesting. Given the opportunity to do work for a magazine that featured predominately creator-owned work, Byrne chose to do a story about Galactus and Nova, two Marvel-owned characters (although Byrne did create Nova). It seems like something that should have been a subplot in Fantastic Four rather than a stand-alone tale. Despite a notice in the magazine promising to finish the story in a future Epic special, “The Last Galactus Story” would never be completed. Byrne left Marvel somewhat abruptly, leaving storylines in Fantastic Four and The Incredible Hulk unfinished as well.

And all the rest, including some leftovers

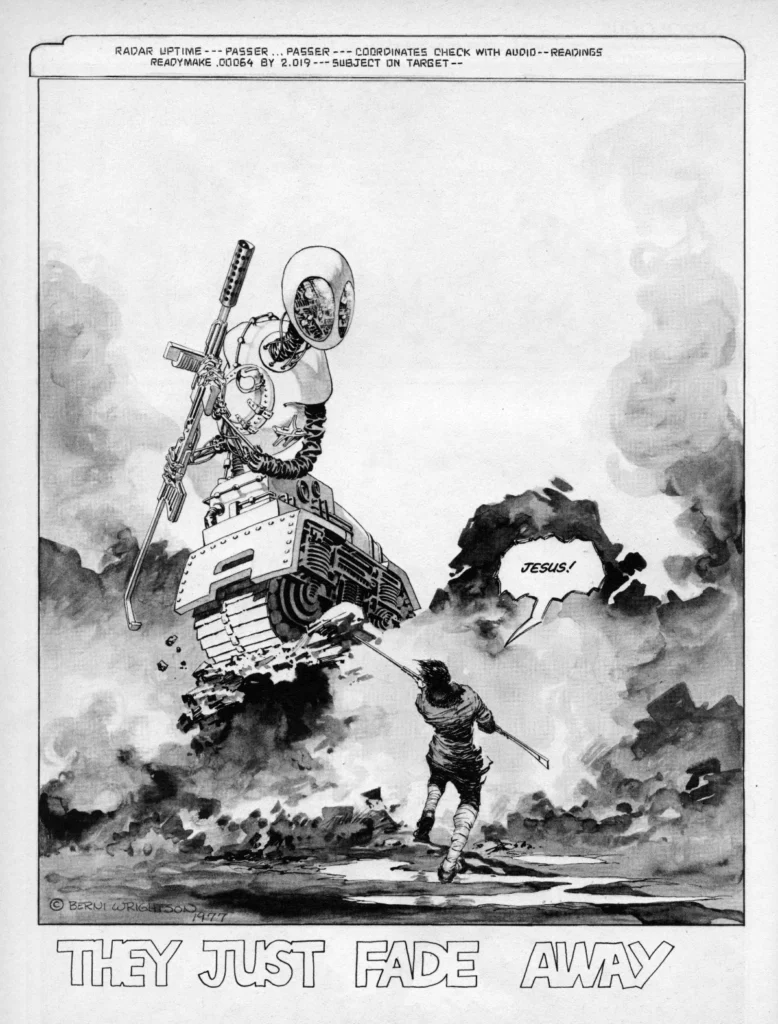

The issue is rounded out with a few more stories featuring recurring characters: Dr Watchstop by Ken Macklin and Cholly & Flytrap by Peter Koch and Arthur Suydam. Also appearing are a handful of winning entries from an illustrated story contest held at the Atlanta Fantasy Fair in 1985. Additionally, the issue features two pieces by noted comics creators Bernie Wrightson and Jim Starlin that had apparently been languishing in a drawer since 1978. Starlin’s piece is well drawn but seems almost like student work. Wrightson’s, on the other hand, is a terrific little Twilight Zone-style science fiction tale.

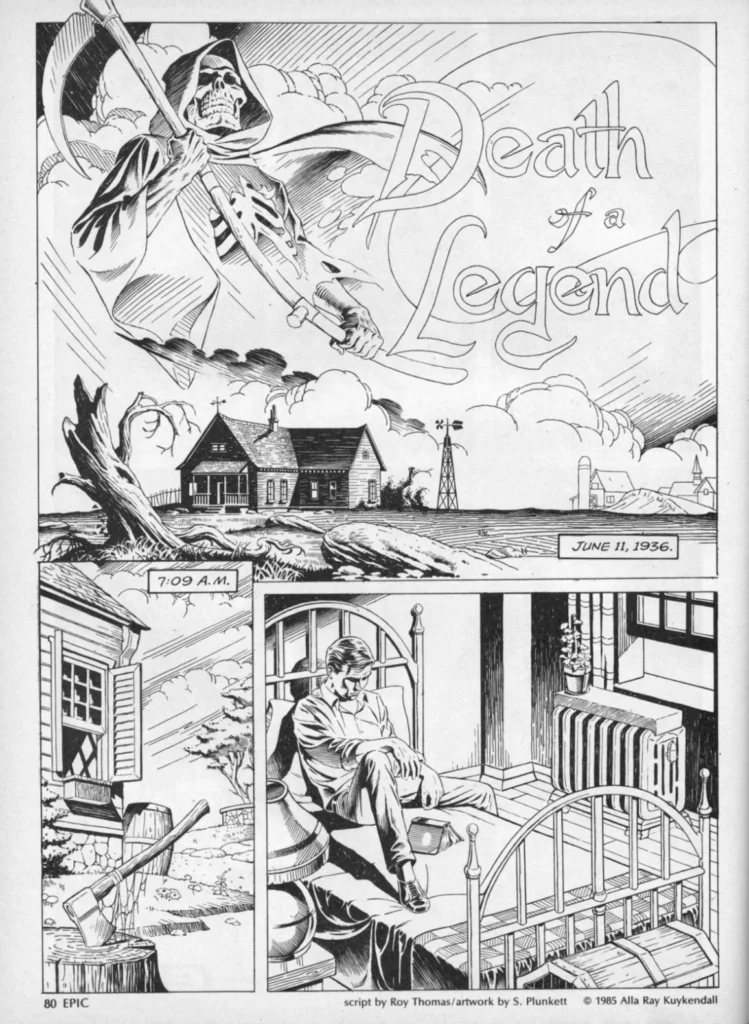

Finally, we have “Death of a Legend,” written by long-time Conan the Barbarian comics writer Roy Thomas, with artwork by Sandy Plunkett. This story about the death of noted fantasy author and Conan creator Robert E. Howard is in some ways the high mark of the issue. But at the same time it relies heavily on the reader already being familiar with Howard and his creations. Perhaps it’s a safe bet for readers of an illustrated fantasy magazine. It certainly makes sense for inclusion in that magazine’s final issue.