Alan Moore had big ideas for DC Comics’ recently acquired Charlton Action Heroes, but the publisher had other plans…

It has been well established over the years that early drafts of Alan Moore’s Watchmen featured the Charlton Action Heroes, a group of characters originally published between 1954 and 1967 by Charlton Comics and later acquired by DC. Moore’s plans would have radically changed the characters, and (spoiler alert!) killed most of them off by the end of the series. Given that Watchmen turned out to be such a phenomenal success for DC, they could easily have justified the cost of acquiring the characters just for the one twelve issue series, but no one involved could have known that at the time.

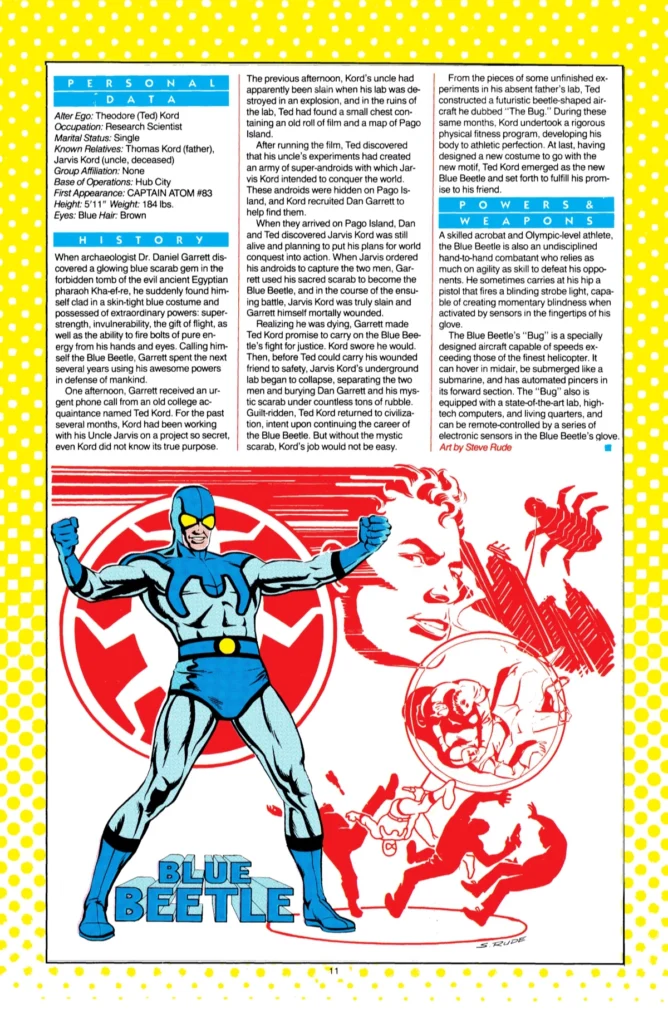

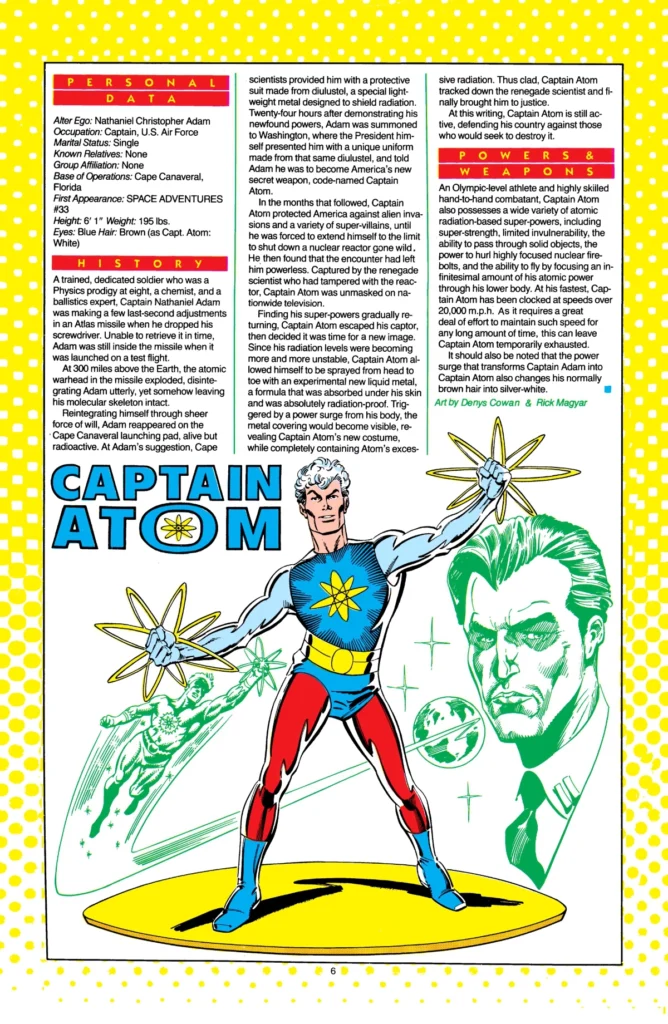

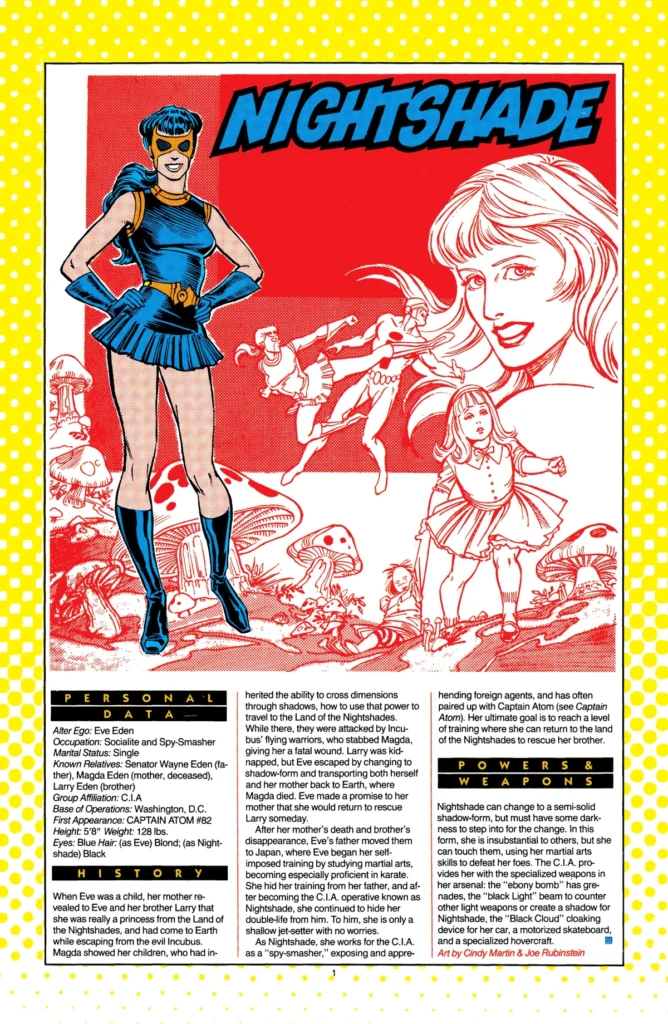

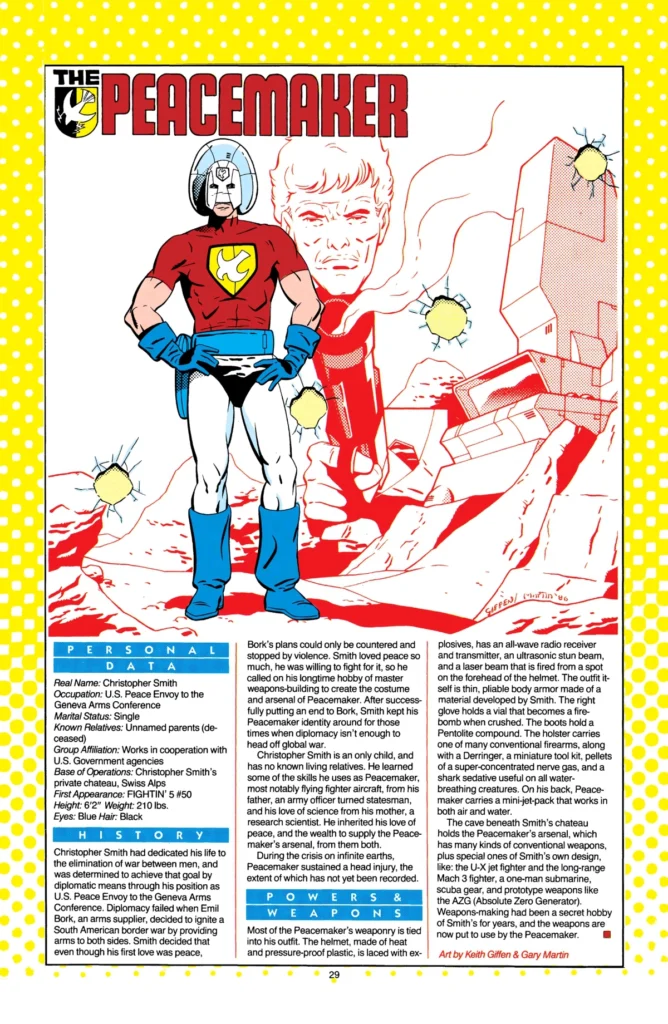

As recounted by Robert Greenberger in Back Issue! magazine #79, the story goes that DC’s then vice president Paul Levitz bought the rights to the characters as a gift for DC Executive Editor Dick Giordano, who had worked at Charlton earlier in his career and had a lot of affection for the characters. Whether or not that is true, DC would still expect a return on their investment. Giordano and DC clearly had plans to fit the Charlton Action Heroes into the larger DC universe – all of the primary characters appear in Who’s Who: the Definitive Directory of the DC Universe, starting with Blue Beetle in #3, published in January 1985 (cover date: May 1985).

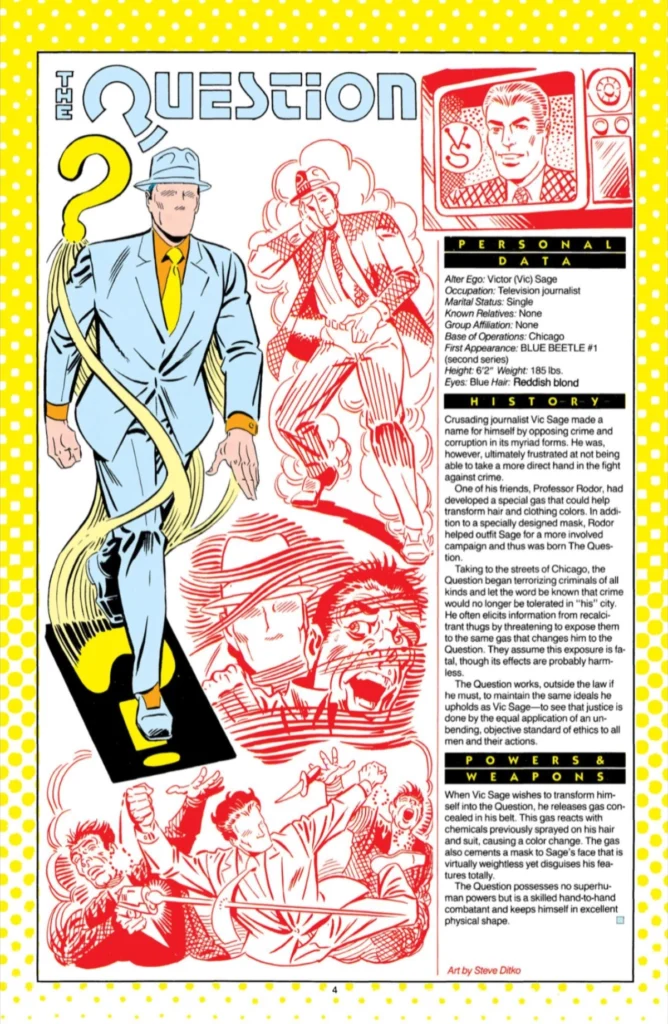

Pages from Who’s Who: The Definitive Directory of the DC Universe. © DC Comics.

With the Charlton heroes unavailable to him, Moore created a new cast of characters for his story,with some remaining closer to their original inspirations than others. Meanwhile, after a few false starts, DC set out to update the Charlton characters and put them in front of a modern audience.

Blue Beetle takes the DC Universe by storm

The first Charlton Action Hero to appear in DC continuity was the Blue Beetle. He was initially featured as a secondary character in Crisis on Infinite Earths, starting with the first issue in December 1984 (cover date April 1985). Crisis was a big event series designed to streamline and combine all the various alternate realities that had featured in DC’s comics over the previous 50 years, a perfect opportunity to throw in a handful of characters whose earlier adventures had come from another publisher.

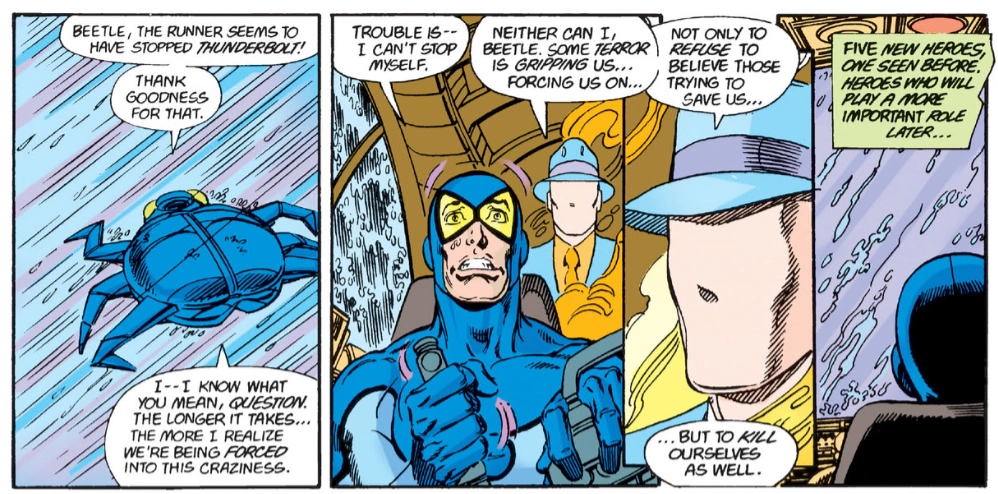

Blue Beetle’s origin was retold by writer Len Wein and artist Gil Kane in Secret Origins #2, published in January 1986 (cover date: May 1986), with a story that leans into the legacy aspect of the character. Charlton had originally published the character in 1964 as Dan Garrett, an archaeologist who gets vague, undefined superpowers from a mystical scarab he finds in an Egyptian tomb. The Blue Beetle was later retooled as Ted Kord, a millionaire industrialist whose crimefighting abilities come from technological gadgets. Charlton’s Blue Beetle #2 (August, 1967) reveals the connection between the two versions of the character, and the 1986 Secret Origins issue sticks pretty close to this story.

The first half of the story recounts Dan Garrett’s origin as the original Blue Beetle. Then the scene shifts to a nearly word-for-word retelling of the 1967 Blue Beetle #2. Ted Kord, a former student of Garrett’s, comes to him for help. His uncle Jarvis is holed up on an island building an army of killer robots. The pair mount an expedition to the island, where they are immediately captured, forcing Garrett to reveal that he is the Blue Beetle. They manage to escape and destroy the robot factory, but Garrett is killed in the process, inspiring Kord to carry on his legacy as the new Blue Beetle.

Blue Beetle settles in

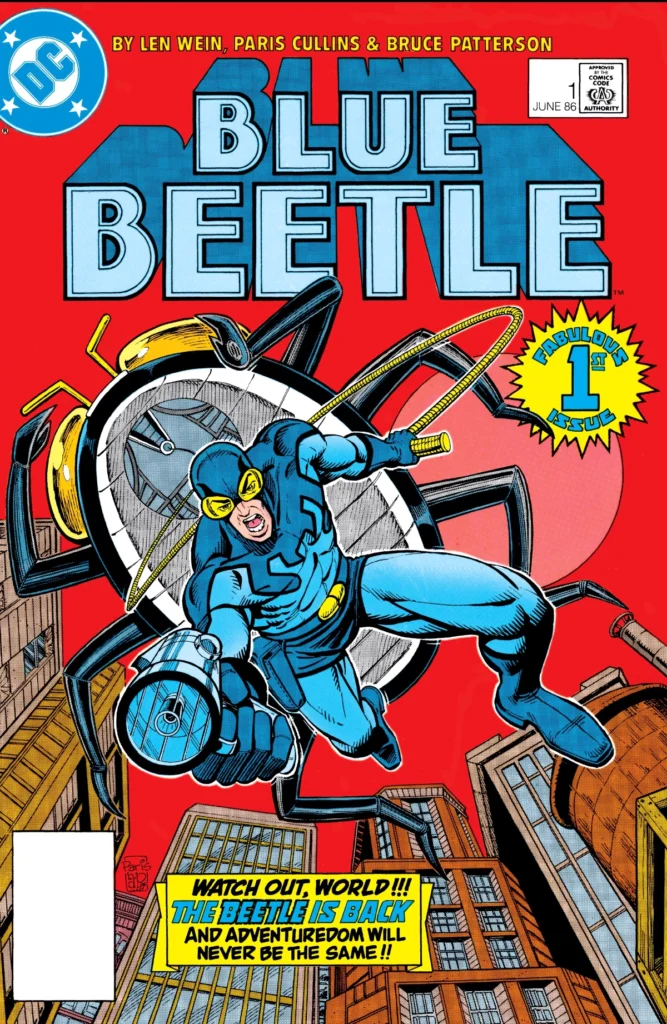

DC’s Blue Beetle #1 (February 1986, cover date June 1986) takes advantage of not needing to retell the origin story again, instead dropping us right into some classic superhero action as the Blue Beetle arrives at a burning building and gets into an altercation with Firefist, an armored, fire-setting supervillain.

We’re treated to a few hints about how the Beetle has returned to superheroics after an unexplained absence, a meta reference to the 19 year gap between his previous self-titled series and this one. The villain escapes (possibly promising to be part of an ongoing storyline) and after a brief recap of the Secret Origins story, we are introduced to what will be the status quo for the series.

Ted Kord is the owner of Kord Industries, a technology company that conveniently gives him the resources to keep up his array of Blue Beetle gadgets, including the Bug, a flying, submersible craft that gets him around the city. He’s got a secretary who appears to be stealing technology from him, a girlfriend who also works for him as a research scientist, and a friend at S.T.A.R. Labs (DC’s recurring source of “technology gone wrong” storylines) who calls him in on cases.

Writer Len Wein deftly sets up several recurring plot threads, including one about a policeman investigating the disappearance of Dan Garrett that’s lifted from the original 1967 Blue Beetle series. These threads are developed over the course of the next several issues and feature only the most casual connections to the wider DC universe.

It seems that the creators want to firmly establish Blue Beetle as “his own man,” without relying too much on references to other DC characters – the book has its own solid cast of supporting characters and several ongoing storylines. Artist Paris Cullins complements this approach, giving the book a distinct look, different from DC’s house style and right on the edge between cartoon and realism. The style is fluid enough that the characters can have exaggerated, expressive faces, but we can still take the action seriously when we need to.

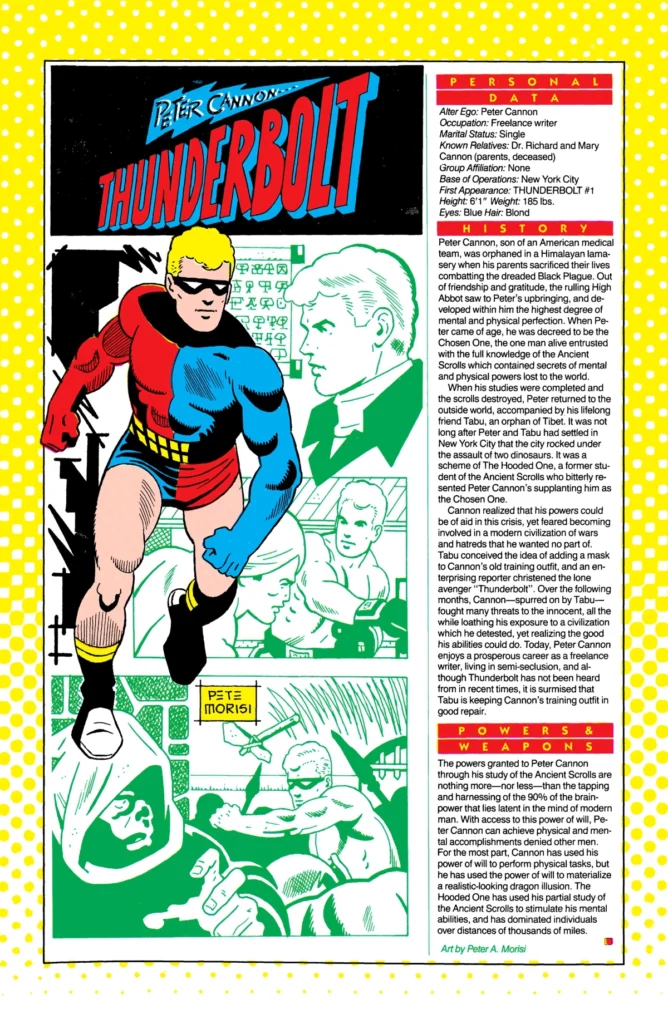

A preliminary Question

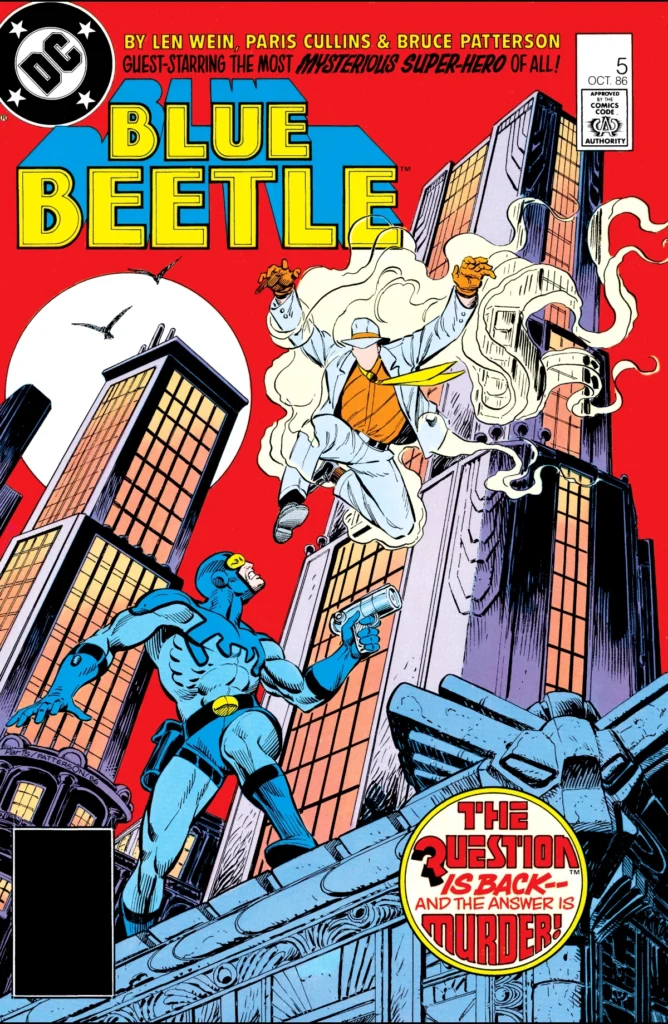

Blue Beetle #5 reintroduces the Question, Charlton’s esoteric detective created by Spider-Man and Doctor Strange co-creator Steve Ditko. Blue Beetle and the Question team up to investigate a mysterious new villain called The Muse and his attempt to unite Chicago’s street gangs in a turf war against the established organized crime syndicate. In a startling turn of events, the crime boss’ son turns out to be the Muse – he just wants to be an actor and sees destroying his father’s criminal organization as the only way to avoid having to take over the reins. It’s all fairly predictable and cliché ridden, but it does introduce the Question without spending a lot of time on an origin story.

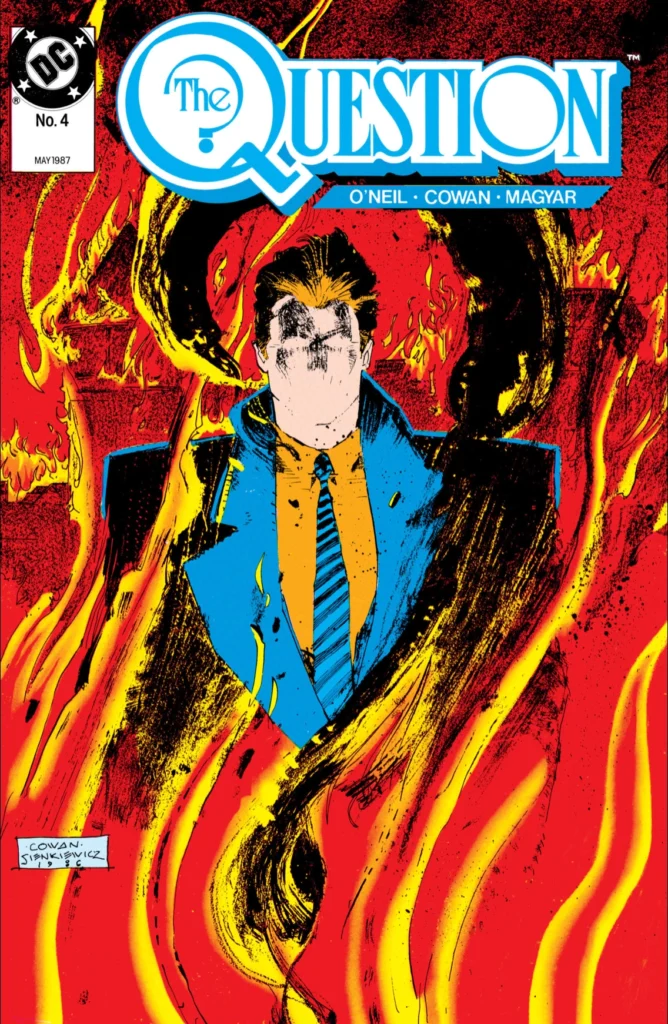

It is worth noting that, rather than team Blue Beetle with an established DC character and help cement his position in the wider continuity, they chose to feature another Charlton hero. It establishes a connection between the new arrivals to the DC universe that won’t be revisited any time soon. The Question returned in his own series just a few months later, retooled with a much darker tone that would keep him confined to the “grim and gritty” corner of the DC Universe populated by the likes of Batman and Green Arrow.

Blue Beetle vs. Nite Owl

It seems unlikely that Alan Moore would have been privy to any details of the new Blue Beetle series, so the fact that Watchmen’s Nite Owl is so close in concept demonstrates how little the character has been changed from his 1967 origins. In Ted Kord, Moore had a character who would be motivated and empowered by invention and technology rather than physical violence, giving him a more reasonable viewpoint character who wouldn’t be as prone to the excesses he was going to assign to many of the other Watchmen characters.

Ted Kord’s relationship with the earlier Blue Beetle is also reflected in Watchmen. Moore gives Dan Dreiberg/Nite Owl a similar connection to an earlier hero with the same name, and it is a critical part of Watchmen’s structure. For the earlier Nite Owl, Moore wisely dropped the sillier details of the first Blue Beetle’s origin, removing all trace of anything supernatural and making him merely a costumed crimefighter – I wonder if he would have done anything differently if he’d been able to use the actual Charlton characters as originally planned.

Peacemaker slips in under the radar

It makes sense that Blue Beetle, the Question, and the forthcoming Captain Atom would be the Charlton heroes given the most attention, as DC didn’t have any characters in its stable that were much like them. In contrast, they seemed to have a harder time figuring out what to do with Peacemaker. He was initially cast as a villain in one of their early “mature readers” titles, Vigilante, with a level of insanity added to the character that doesn’t seem to be present in the Charlton version.

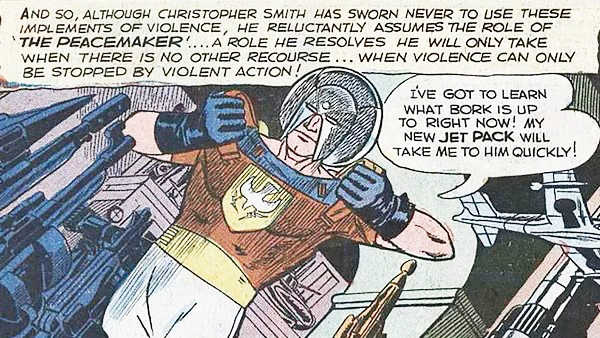

The original Peacemaker, from Fightin’ 5 #40. Story by Joe Gill, artwork by Pat Boyette. © DC Comics.

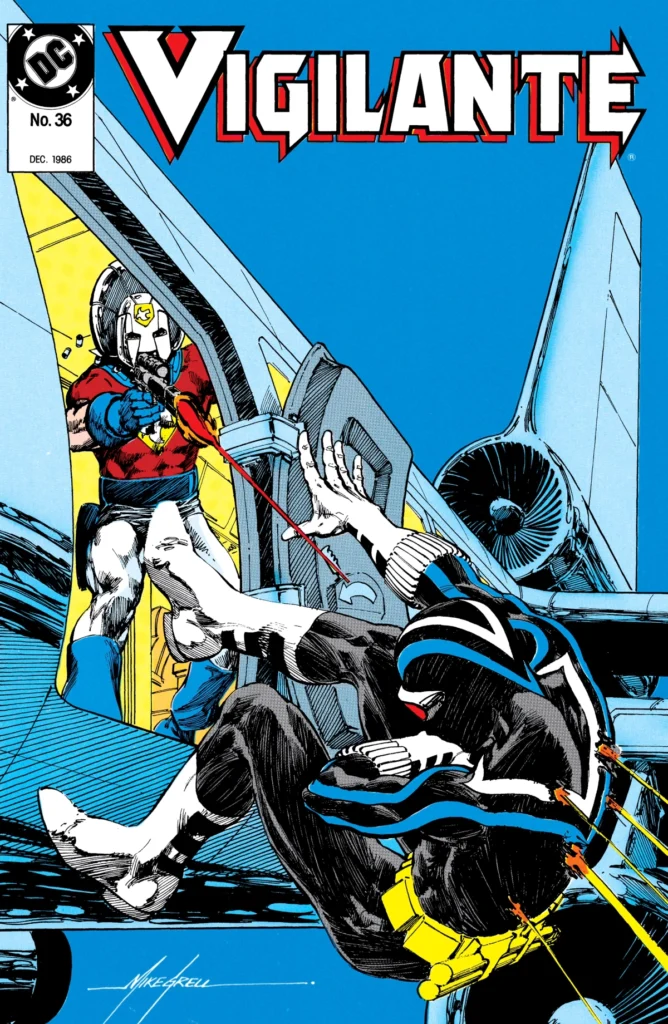

The character’s reintroduction in Vigilante #36 (cover date December 1986) adds a very 1980s detail: the Peacemaker believes that the souls of everyone he kills inhabit his helmet, and they speak to him in a cacophony of guilt and recrimination. It is unclear whether this is the cause or the result of his seemingly callous disregard for human life and collateral damage, but it does allow Vigilante writer Paul Kupperberg to cast the Peacemaker as a rogue agent that the government has lost control of.

The story which unfolds over the next three issues is a little convoluted, especially if you’re not familiar with the ongoing storyline in Vigilante. Original Vigilante Adrian Chase has retired from crimefighting and passed on the mantle to a colleague, who is killed in the crossfire when Peacemaker shows up to foil an airplane hijacking. Naturally, Adrian Chase just happens to be a passenger on the plane, and upon witnessing the death of his protegé, reclaims the Vigilante identity and vows revenge.

Peacemaker vs. The Comedian

The Vigilante is definitely more Punisher than Batman, appearing to be motivated purely by revenge and a desire to punish the guilty rather than protect the innocent. The Peacemaker is presented here as cut from the same cloth, with the added wrinkle that he’s completely insane. This unfortunately means that his motivations don’t have to make sense, making him much less interesting as a character.

Again, it’s interesting that in spite of most likely not knowing what Paul Kupperberg planned to do with the character, Alan Moore went down a similar path. Watchmen’s Peacemaker stand-in is completely devoid of a moral center – perhaps it’s the original character’s background as a government operative that led both writers to this same conclusion. The Comedian acts from a high degree of nihilism rather than outright insanity, which is an important distinction. As the character whose death sets the plot of Watchmen in motion, Moore needs the reader to find the Comedian interesting, even when he is profoundly unlikable, and he manages to do that without making him cartoonishly insane or even giving him a tragic background, which would only have served to bog down the story.

Nightshade or Black Canary?

Common wisdom has it that Watchmen’s Silk Spectre is based on Charlton’s Nightshade, but in fact the two characters have very little in common. Nightshade is an overtly supernatural character who can assume the properties of a “living shadow” and open teleportation portals. Her origin is tied to a mystical realm called “The Land of the Nightshades” where her brother Larry was kidnapped by demons.

After appearing in Crisis on Infinite Earths with the rest of the Charlton characters, Nightshade was assimilated into mainstream DC continuity, first as a villain in Suicide Squad #1 (February 1987) and later as part of various ensemble teams. But unlike the majority of her fellow Charlton heroes, she never made the jump into her own title.

The association with Silk Spectre seems largely due to Nightshade being the only prominent female Charlton character, and her having a relationship with Captain Atom, although theirs is depicted as being much more professional in nature. Nightshade’s fairy-tale origin story and overtly supernatural powers would not have fit with Alan Moore’s naturalistic approach to Watchmen, where Dr. Manhattan is the only superhuman character.

It seems more likely that Moore drew inspiration from Black Canary, a leather and fishnet clad female crimefighter that had been appearing in various DC books since 1947. Justice League of America #220 (July 1983, cover dated November) introduces a legacy element to Black Canary’s origin story, with Dinah Drake originating the identity in the 1940s and later turning it over to her daughter. In Watchmen, Silk Spectre has the same mother/daughter background, which helps them fit in with Moore’s multi-generational story.

To be continued…

Next time we’ll look at the the basis for Watchmen’s two most compelling characters, as well as the one who didn’t quite manage to make a mark on the DC Universe.

The Question #4 (May 1987). Cover artwork by Denys Cowan and Bill Sienkiewicz. © DC Comics.